rants

Blame the mother 2.0

Decades of science have helped us better understand autism and meet autistic individuals where they are. But a few weeks ago, the White House looked at all that human progress and apparently decided to make everyone look away while they attempt to put the toothpaste back in the tube. If it was unclear to you whether to be distracted by acetaminophen or childhood vaccines, that was on purpose. Their aim was getting autism back in the headlines for a fresh round of mom-shaming.

Many autism advocates caught on immediately, and some news outlets, such as The 19th News (Sept. 30, “MAHA frames autism around mother blaming”), are starting to catch up. But as we know, the lies can get pretty far ahead while the truth-tellers are still lacing up their running shoes. We also have been conditioned to believe that mothers can be dangerous to their children’s health. It’s easy imagine, then, that Refrigerator Mother 2.0 may find renewed traction, rolling back the progress we’ve made for autistic individuals and society at large.

The “refrigerator mother” theory dates from 1943, when Leo Kanner wrote his landmark paper on autism. He claimed a lack of maternal warmth created the condition and said that autistic children “were left neatly in refrigerators which did not defrost.” A few years later, Time magazine brought the concept to the masses.

The theory stuck for decades, in part because genetic scientists and other researchers—the truth-tellers—were still putting on their shoes. It’s human nature to blame others when our troubles feel intractable. And blaming mothers has been a long-running cultural tactic. Law professor Linda Fentiman’s recent book, Blaming Mothers: American Law and the Risks to Children’s Health, shows how our supposedly neutral laws actually treat mothers (and those who are pregnant) as risk vectors. Take it from a worn-out mother who’s been blamed plenty for her son’s autism over the decades: shiny new wrappers don’t hide this destructive pattern of human behavior.

However, in the last 40 years, scientists have also given us a stunning amount of knowledge. They are starting to untangle what we need to know about our genes and the environment in relation to autism. More importantly, they are creating the space for autistic individuals to learn and for the rest of us to understand how best to respond. Autism has physical and biological attributes, but the way we respond reveals our social constructs and the way that often limits the options for everyone. Ramps can improve everyone’s mobility. Movies with captions help viewer’s comprehension. Audio cues make busy intersections more comprehensible to us all.

Families love their children, so it’s safe to say that they want to meet their responsibility to raise their autistic child as best they can. Those of us that know and understand science, including the science of autism, may well be inoculated against mother-blaming. We owe it to our children, and their children, and our communities to resist the rollout of Refrigerator Mother 2.0 and instead share the scientific understandings that have improved our quality of life.

Fledging

Late last week, walking with Fang, we came upon a red-shouldered hawk that had just made a kill near Rayzor Ranch Park. She was standing in a field with the varmint in her talons. The varmint seemed a little too silky brown and big to be a rabbit. There are a few jackrabbits in what is left of the old Rayzor Ranch. Or it could’ve been a nutria from the nearby retention pond.

I have seen this a few times before, this waiting after a kill. Once, a hawk had landed on a rat running in our postage stamp of a backyard in California. We watched through the dining room window as the hawk waited patiently until it was safe to fly off with her prey.

But this time, a scissor tail from the park decided there was no room in the new ‘hood for a hawk. I watched in wonder as the scissor tail dove for the hawk’s back, triggering the raptor to drop its prey and lift off. The scissor tail rode on that hawk’s back for a few hundred yards before veering off and back to the park.

I knew why she was doing that. A few days before, we were walking to that park (Fang likes Rayzor Ranch Park a lot.) At one point, I was almost face to face with a pair of scissor tails fledging their young — three little guys who didn’t have their scissor feathers yet, but were flying pretty well. They had just regrouped in one of the younger trees in the park, so they were barely hidden. The parents had tucked wings and tail feathers around them, as they all wiggled and peeped and got ready to fly again. We caught up with them a second time not far away, all three fledglings perched on a fence, side by side, peeping and wiggling and trying to decide whether Fang and I warranted another flight attempt as their parents flew overhead.

The sight of it all triggered a fast rewind in my brain, other times we’ve stumbled on fledging as we’ve walked. Once in a neighborhood to the east, a fledgling raptor had to be nearby–although I never saw it–because a Mississippi kite grazed me three times until we finally went around a corner. (I was so glad to be wearing a sturdy hat.)

Another time, I saw a pair of mourning doves standing unusually close to one another, perched on the next-door neighbor’s roof. I looked around and saw the fledgling in the gutter. The little guy wasn’t going to make it. I scooped up its body the next day.

Another time I didn’t see the fledgling until just after Fang spotted it hopping in the leaf litter beneath the oaks in McKenna Park. First the momma robin dove at Fang, and then the poppa. Fang immediately lost interest in the fledgling and was already crying uncle. But a call went out anyways and within seconds, every robin in the park was diving at the two of us, like a Hitchcock horror movie.

I got curious about how much scientists know about fledging and bird behavior. We don’t know a whole lot. I found a research study from 2018. This study suggested to researchers that fledging is negotiated between the young and the parents, with different species tolerating longer stays than others. Young birds that leave before they can fly very well have a higher mortality rate, of course. The scissor tails certainly had to fledge before their tails got too long, as my own mother adeptly noted. But the young that stay too long risk discovery by predators who bring jeopardy to the entire nest, parents included.

I’m not sure how well we humans do at fledging. Actually, in terms of survival of the human race, rather poorly, I think. We understand child development a little better than adult development. New research suggests a stage of emerging adulthood that warrants our closer attention. And, as most of us disability parents will tell you, fledging a child with a disability is tough. We have organized our culture in ways that discourage cooperation and care for one another, unless doing it for money. Can you imagine being like a robin and joining the entire flock to defend someone else’s child? We are too fond of gaming the economic rules so that one group or another gains an edge, instead of raising all boats. We do this change-up so often that it’s hard even for kids without disabilities to launch.

Maybe there’s a reason we know we are doomed. Maybe there are lessons from nature. Before it’s too late.

A rose behind a geofence is just a rose, fenced

The word geofence joined the English language in the mid-1990s. As I type the word “geofence”, Microsoft Word doesn’t correct my spelling—yet, chances are high that if I want to talk with Sam about geofencing, the first thing we would have to do is talk about the word’s definition in plain language.

Sam inspired me to become a plain language fan. It’s not just because we now have the Plain Writing Act of 2010, a federal law that sets the standards for certain government agencies to better communicate with people.

When talking with Sam in plain language, we usually find some great truths. We have to be thinking very clearly to boil stuff down to its essence. And then Sam, always a great thinker, figures out what that essence means and where that new essence belongs in his life.

So, the word “geofence” in plain language: A boundary line on your computer.

We sometimes say that good fences make good neighbors. The poet Robert Frost had more to say about that. In other words, a fence on a computer has meaning, too.

Our local transit agency, DCTA, experimented with a computer fence to offer van rides to the west side of town a few years ago. Sam used that van service to get to work a few times. It was very hard. I rode with him once. First, you had to travel to the fence line, then you could hail the van that only gave you rides inside the fence lines.

The day I went with him, I had to wait a half-hour to ride back to the other side of the fence. While waiting, I saw dozens of DCTA vans driving Peterbilt workers to destinations that I knew were traveling far beyond the fence lines I was traveling in.

Recently, our transit agency has drawn new fence lines for van rides. At first glance, the big pasture of service seems generous. But at the same time, they also cut most of the buses whose lines weren’t fences, but veins.

Suddenly, yet predictably, too many riders are coming from certain areas. DCTA says they may “geofence to manage demand.”

Or, in plain language: they will draw lines that push riders out.

Sam has told me more than once that he wants to ride bus to work. I began to doubt whether that would ever happen after I saw the long line of Peterbilt-subsidized DCTA vanpools. Then, when an apartment developer paid extra for DCTA to run a bus to its massive apartment complex adjacent to the warehouse district (beyond even the millions UNT pays DCTA to run buses), I gave up hope. We don’t, and probably won’t ever, have a system to serve the thousands of people like Sam, who can make their lives better with the mobility that connects them to economic opportunities–let alone the magical world that exists for all of us when our community has that kind of mobility.

Some politicians (and their constituents, of course) will always be attracted to lines like geofencing. Playground games follow the boundary lines. Winners and losers are determined by the lines. And, as we all know, some kids aren’t allowed inside the boundaries to play at all.

I doubt our transit agency board recognizes the deepest meaning of its actions as it draws these lines. The longer they allow those fence lines to exist on computers, the more those lines become real-life walls.

Reagan was wrong. There is no trust when you must verify.

The first time I took Sam to school and left him for a full day was a big leap of faith. I wasn’t alone, of course. Parents want to protect their kids. And parenting a child with autism or other disability puts that protective feeling into overdrive. Eventually I saw that we weren’t alone. His many teachers and therapists were part of his village. Later that year, I walked into a special education team meeting and recognized that, for the first time in Sam’s young life, I was not “on call” for every minute of every day. It was such a nice feeling, one that left room for more thinking and reflecting about our lives, and for resting, too.

That’s not to say that his school years were perfect. We knew not everyone in his life would be as mindful. But we also knew that the perfect is the enemy of the good. When conditions warranted, someone at school picked up the phone and told us about an emerging problem. We addressed many small things before they got big. And we learned to celebrate the average and the good enough, which was its own kind of achievement for Mark and me.

So (and you knew there was a so, didn’t you, dear internet people?), I struggle deeply with the burgeoning installment of security cameras at school. We aren’t just pointing cameras at the school’s exterior doors. Or in the hallways. Or from the school resource officer’s body armor. We are pointing them inside the classrooms, too.

In Texas, parents can ask for a camera in their child’s special education classroom. The school must get consent from parents of the other kids in the class, but such camera use is on the rise. Advocates for kids with disabilities continue to press the legislature for broadening a family’s rights to footage. One day, some parent will send their child with a disability to school with a body camera if they believe it’s necessary.

I recognize that school can be a rough place for children who don’t fit in for one arbitrary reason or another. Sam was getting hassled in the boys’ bathroom one year, and solving the problem proved tricky for the aides, both women. But we figured it out.

I recognize also that some schools are hard pressed to fill their teaching ranks. There are employees without enough skills to work with and manage kids, the place where most tragedies begin.

This is not to say that people in our community might have different values from my family’s or yours. As a culture, we wobble too much in figuring out how to work with those differences as strengths and educate our children. But I have to say, where parents are asking for cameras, we aren’t reading those huge warning flags.

When Sam graduated high school, I wanted everyone from elementary school on up to have a “Team Sam” button as a little token of our esteem and affection. I ordered 250 buttons and did not come close to gifting all those people who touched his life and helped him make progress. Dozens of teachers, of course, but also speech therapists who worked with him on communication skills. Occupational therapists and adaptive physical education teachers who helped him with his motor planning and ability to calm himself. School counselors who helped him build friendships. Aides who helped him stay on task in class and occasionally take a moment to decompress when he couldn’t. And the principals and other staff who stood by and made sure all those people had the support they needed.

I had to trust these people. All of them. A lot.

There was no “trust but verify.” Where there are cameras, there is no trust.

Small, little men

The national media is noting the ignorance and cruelty in Texas public policy, including the new laws that ban abortion and suppress voting rights. I would argue that the state’s policies and governance vis-à-vis people with disabilities amply demonstrates that this ignorance and cruelty isn’t new.

Elected officials in Texas have refused for years to adequately fund the medical and disability services that allow individuals to live in the community and avoid costly (especially to taxpayers) institutional care. Federal programs can pay the lion’s share of these services, and in most other states they do, but Texas refuses to expand Medicaid enough to allow that to happen. Instead, they authorize puny levels of funding for “waiver” programs—part of the federal law that allows Texas and other states to opt out with the promise to take care of people in their own way. But really what Texas does is pretend the burden doesn’t exist. Instead of fostering human progress, Texas disability policies hardwire families and communities for long-term suffering.

Sam was in kindergarten when we first moved to Texas. We followed the advice of the good people at Denton MHMR and put his name on one of the infamous waiting lists for the state’s waiver programs. Our social worker said that even though we couldn’t be sure then what services Sam might need when he was 18, we’d have no chance at help if he wasn’t on a waiting list. At the time, we were among the young families that got a little help paying for respite care and for special equipment, so we picked the waiting list for the waiver program most like that.

(Sadly, a year or two later, even that modest state program for young families ended. We were on our own.)

Families who are able to access services under these sparsely funded waiver programs understand them much better than I do. Sam made enough progress and adapted well enough that he doesn’t need the help—the kind of basic human need that tends to make allies and advocates into battle-hardened experts in the shortcomings of public policy.

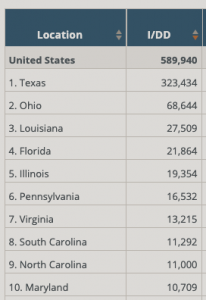

But I do know that the Texas waiting lists for waiver programs are cruelly long. Nationwide, there are about 600,000 people on a waiting list and more than half of them are on a list in Texas. (For context, remember that less than 9 percent of the nation’s population lives in Texas.)

In its latest budget, the Texas Legislature funded additional slots to get more people into the waiver programs, but not nearly enough. Some advocates and self-advocates have done the math: the Texas list is so long that individuals could wait their whole lives and never receive services.

When other states would get in this deep, they agreed to Medicaid expansion made possible by the Affordable Care Act. Waiting lists for waiver programs in those states nearly disappeared because Medicaid expansion stepped in to fund those services.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Texas is among just 12 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. Texas is, by far, the most populous state to refuse to provide services at a meaningful level and make no real progress toward that goal.

Some advocates wonder whether the U.S. Department of Justice will intervene, especially when U.S. Department of Health and Human Services officials seemed to wobble on approving the state’s waiver program earlier this year. It’s a great question, but we need look no further than the state’s troubled institutions—called state supported living centers—to see how a negotiated settlement might go. Independent federal monitors have visited those centers since 2009, after fresh reports of abuse and neglect emerged with cellphone video of a “fight club” forced on residents at the Corpus Christi center. All 13 centers were supposed to meet negotiated standards by 2014 or face further action, up to and including closure. Twelve years later, none of the centers (home to about 4,000 people with developmental disabilities) met the standards, the monitors still make regular visits, and all 13 centers remain open at increasingly unsustainable costs to state taxpayers.

Texas is growing fast and its people need a far more robust physical and social infrastructure than state officials seem to grasp. Some people see our governor moving about in a wheelchair and think he’s got the disability thing covered. But advocates know better. “He’s not one of us,” I heard one self-advocate say recently, pointing out the many, many differences between an individual who must adapt their entire life when compared to the governor’s experience, where the need for a wheelchair came much later in a life of privilege.

These days, Texans are watching their governor and the other small, little men in state leadership race to the bottom in a panic to maintain power. In that twisted race, their lawmaking and policies are displaying new levels of ignorance and cruelty for all to see. But color me not surprised, as the ignorance and cruelty has been part of their law- and policymaking for our community for a very long time.

Refrigerator Mother 2.0

Only a few generations ago, some doctors blamed mothers for their children’s autism. Psychologists wrote long theoretical papers based on their observations of mothers and their children. They concluded that autism mothers were cold and that their lack of love triggered the child’s autism.

If you stop to think about that idea for a minute, those explanations were quite a leap. And a cruel one at that.

We humans look for patterns in the world around us–it’s almost one of our super-powers. We use the information to make meaning, and create loops of ferocious thinking that make the world around us a little better.

Therefore, knowing that we’re supposed to make things better, the Refrigerator Mother explanation for autism just begs the question. How much did those early theoreticians consider and—most importantly, rule out—before concluding they’d observed a pattern of mothers who don’t love their children?

Granted, many people were immediately skeptical of these mother-blaming theories, including other professionals and autism families. The theories fell after a generation, but the damage was done to the families forced to live under that cloud as they raised their children.

And, the blame game is still out there.

The latest iteration has started in a similar way, with people seeing problematic patterns in autism treatment. Young adults with autism are finding their way in the world. Some of them had good support growing up, but the world isn’t ready for them. Some of them had inadequate support growing up, so they have an added burden as they make their way in a world that isn’t ready for them either. Some are speaking up not just about the world’s unreadiness but also about that burden. We must listen. Autistic voices can help us find new patterns and new meaning and build a better world for all of us.

We should be careful about letting one person’s experience and voice serve as the representation for the whole, because that’s how the blame game begins. Even back in the old days, when information was scarce, we had the memoirs of Temple Grandin, Sean Barron, and Donna Williams to show us how different the experiences can be. As Dr. Stephen Shore once said, if you’ve met one person with autism, then you’ve met one person with autism.

Here’s an example of how that can break down: some now argue that asking an autistic child to make eye contact, as a part of treatment service, is inherently abusive because eye contact feels bad for them. Missing from that argument is the basic context, the understanding that for humans to survive, we need to connect to one another. For most of us, eye contact is the fundamental way we begin to connect, from the very first time we hold and look at our new baby and our baby looks back at us.

I asked Sam recently (and for the first time) whether making eye contact is hard or painful for him. I told him I was especially curious now that eye contact changed for all of us after living behind face masks for a year. He said this, “Eye contact is very powerful. I wonder whether I make other people uncomfortable with eye contact.”

He’s right. It is powerful. And he just illustrated the point about one person’s perspective.

When Sam was young, we never forced him to look at us. But after a speech therapist suggested using sign language to boost his early communication, I found the sign for “pay attention” often helped us connect.

The additional movement of hands to face usually sparked him to turn his head or approach me or Mark in some way, so we were fairly sure we had his attention and that was enough to proceed with whatever was next. Over the years, we’ve shared eye contact in lots of conversations and tasks. But if not, we recognized the other ways that we were connecting and I didn’t worry about it.

All of this context—both the need to survive and the difficulty with a basic skill needed for that survival—cannot go missing from any conversation about the value of teaching an autistic child. Some people with autism do learn how to make eye contact early on and are fine with it. Some don’t. For this example, then, we can listen carefully to adults with autism and their advocates as they flag patterns from their bad experiences with learning to make eye contact and make changes. But that fundamental need to connect and share attention remains.

That’s when we also need to remember our tendency to blame others when our troubles feel intractable. Sometimes, in these fresh arguments over how autism treatment should proceed, I hear that same, tired pattern of blame I’ve heard since Sam was born. Take it from a worn-out mother who’s been blamed plenty over the years: some arguments are just another round of the same, they just come inside an elaborate wrapper of mother’s-helper blaming instead.

All the families I know truly love their children and are learning how best to respond to them. We can’t forget that parents have a responsibility to raise their child as best they can. Let’s talk, please. But please also, let’s spare the rollout of Refrigerator Mother 2.0, because it could cost us a generation of progress.

Power outages and the power of plain language

Save the warnings by the National Weather Service, our household would not have been prepared for the freezing weather and massive power and water losses Texas suffered last week. From late Sunday night through Thursday afternoon, we endured rolling blackouts as two separate winter storms came through North Texas. Unlike many Texans, we didn’t lose our household plumbing in the cold, but our city’s system lost water pressure and we were without safe drinking water from Wednesday afternoon through Saturday morning. We also had no home internet service for most of the week.

As the meteorologists gave their forecasts, the conditions looked to me much worse than they did in 2011, the last time we had a day of rolling blackouts. Since that debacle, I’d read Ted Koppel’s book “Lights Out,” a sobering assessment of life after a catastrophic grid failure. Sam has friends who eventually gave up on living in Puerto Rico post-Maria. I recognized the incredible risk embedded in that forecast. We prepared like a hurricane was coming, with extra food, water (including filling the bathtub), and other provisions. We sheltered our plumbing as best we could.

If we had been waiting for cues from state or local public officials, we would not have prepared.

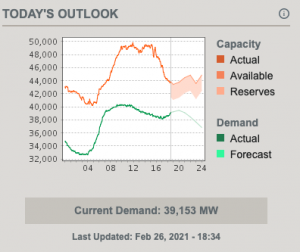

Once the crisis began, it was hard to explain to Sam what was happening. We had little official information to go on. For example, I couldn’t tell him when we might be able to depend on having power again, because no one was saying. I showed him the homepage for the state’s power grid, which has a good visual for what’s happening at the moment. On the outage days, there were bizarre spikes in future capacity, as if ERCOT expected four or five generation facilities to come back online at any moment.

Of course that wasn’t what happened. During the second day of rolling blackouts, we would get a phone call once or twice a day from the city utility, telling us to expect rolling blackouts for the day or night. But those calls said nothing about the grid status or when power would return.

After meteorologists called for warming on Saturday, we made contingency plans to get through to that day. I warned Sam that the power might be unreliable for days or weeks afterward. Power companies had rotated the power off in some places and couldn’t rotate it back on. That could mean the grid is damaged in places, I told him.

Also, when the blackouts started, I couldn’t tell him when the power would be on or off. There was no discernible pattern and we weren’t told. After about 24 hours, the city’s robocalls suggested a basic pattern, although we predicted it more closely using our oven clock as a reverse timer. We also observed street lighting changes as a predictor when we’d be shut off. If it was particularly quiet, Sam could hear the power coming back before the lights went back on. As a result, we could plan for things we needed to do to survive, like prepare food or charge our phones.

But that adaptive mode was ours to determine, and sometimes I had to coach Sam through it. Nothing was ever suggested to us by a public official how to cope with rolling outages, or how cold your home could get before it became too dangerous to sleep there, and the like.

When the city’s water system failed, our city made daily phone calls with recorded messages. They told us when the system was failing and how to help, then they told us when it failed, then they told us how recovery was going, and finally they told us when it was safe to drink again. That communication helped.

Sam does well with most of what adult life throws at him, but one of the few things he still struggles with is “official” communication.

Frankly, we all do better when public officials communicate with us in plain language. That is one reason why the federal government adopted the Plain Writing Act of 2010. I recognize the writing style when I get a letter from the IRS or the Social Security office. They always write in plain language so that even when your situation or the law around it is complicated, they use vocabulary and syntax you can understand so you can act accordingly.

For people with autism, such plain language communication is vital. Sam would likely have suffered greatly in last week’s outage without someone with him to translate what little information we were getting and work to fill in all the voids. ERCOT wrote arcane tweets about load-shedding, for example, and asked people not to run their washing machines. Still shaking my head about that.

We’re both still recovering from the trauma of last week. The trauma was made far, far worse by the lack of communication from state officials. As they set up their circular firing squads in Austin this week, we are learning that they knew this problem was coming and they knew it was a problem of their making. I’m sure individuals were panicking and that made it difficult to make good choices, but that’s why, in calmer moments, they are supposed to write and practice emergency plans. This was foreseeable and preventable. However, in my darkest moments, I sense that the lack of communication was a choice, one they made in part to avoid blame.

This week, I’ve also been stunned by how many people stung by this abject failure expect it to happen again. They simply do not expect our state to be able to fix this mess.

I want to reject that premise, but, mercy me, if it happens again, can they at least have the decency to communicate to us, and in Plain Language?

Informed consent

Sometimes a problem comes through our family’s front door, but because I’ve solved a problem like it before, I don’t feel the worry and anxiety I used to. That’s one thing good about getting older – the been-there-and-done-that feeling gives you confidence.

Even when something new and different comes along, those things aren’t worrisome because there’s a sense you’ve seen some version of it before. Garage sales become eBay. The Sears catalog becomes Amazon. High school’s gossipy mean girls become Facebook.

I would argue, though, that sometimes we forget hard lessons when it suits us. We solved the problem of human experiments years ago and we need to remember the solution applies in many situations.

I wouldn’t have understood the meaning of informed consent if not for raising Sam. Some interventions offered to people with autism and their families can make a real mess. The first time we agreed to participate in a true experiment, I was very grateful for the care the psychology researcher had given, and the university’s institutional review board had reviewed, to make sure our family was fully informed of the risks. You might think an experiment to help Sam and his younger brother learn to play games together wouldn’t need to be deliberately thought through, but it does. Their budding relationship mattered.

I worry about the current ethos; technological innovations are driving a lot of our interactions these days. Eager tech start-ups are taking their barely formed innovations and throwing them out into the world to see what happens without giving any thought to informed consent for fragile families and communities.

For example, I’m not the first person to notice that we are in the middle of a giant experiment with self-driving vehicles–an experiment I don’t ever remember being asked whether I wanted to opt into. A few years ago on a cross country trip, I couldn’t see the driver behind the wheel of a sparkling new big rig bobtailing down the otherwise quiet interstate. As I passed by, I tried to see if the driver was just really short, like me. I didn’t see anyone in the rig. But mostly I remember being upset that if this was some kind of test drive, I was not notified and given the option to take another route. It doesn’t matter that the sale of the automobile is in terminal decline. This experiment needs to be thought through.

When I hear “disruption” or “creative destruction” or some other jargon, it’s been-there-done-that. The words are usually masking an experiment the inventor or company hopes will make them money, and taking everyone’s resilience for granted.

Let’s not.

A year to be more open and connected

Two years ago, after writing a news story about a few of our clever readers and what they learned achieving their New Year’s resolutions, I did mine differently. A year into my own experiment, I had learned so much that I shared it in a column.

That first goal to not buy anything (with reasonable exceptions for food and fixing things) reinforced a simpler, more sustainable life. My next resolution, “Yes, please,” was meant to be this year’s yang to last year’s yin of “no, thank you.”

The idea wasn’t that “yes, please” was permission to give into impulses or rationalized needs, but to push through whatever had been stopping me from trying something new. How else to see the world unless you push through to the other side? I made a list of about a dozen challenges that have been nagging for years; for example, learning to better maintain my bike, sew upholstery, broaden my computer skills, speak conversationally in another language, and make cheese. But if something new crossed my doorstep, like when my friend and brilliant textile artist Carla offered a day of indigo dyeing, I said “yes.” I said yes whenever I could.

Not only is life simpler and more sustainable, but it’s also richer and more fun.

That brought the social media expression of my life into sharp relief. For the coming year, I will co-opt Facebook’s stated mission, to be more open and connected, by quitting Facebook.

The main reason to shut down my account is one that has nagged me for a long time. Facebook’s real mission is nothing like its stated mission. For example, I’ve noticed there are people you cannot reach any other way than through Facebook. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. In Texas, we might share a lemonade on the porch and we’re cordial, but we just don’t invite everyone inside. So I would argue that when you can’t reach someone except through Facebook, then you aren’t really connected at all. Facebook is managing your relationships for you through the veneer of being “open” and “connected.”

I set up the Family Room blog as a place to explore ideas related to living with autism. It’s interesting that most readers come here via a Facebook link and will return to Facebook to comment on the topic, rather than connecting below and creating our own community–which, by the way, is not open to exploitation by a third party because I filter and delete all that garbage.

That’s Facebook’s real mission. And, they “move fast and break things.” After I watched Frontline’s two-part special, The Facebook Dilemma, I couldn’t be a part of it anymore. American newspapers are struggling because Facebook (and similar businesses) got the rules changed: they can publish with impunity while newspapers must continue to publish responsibly. It’s expensive to be a responsible company. But it’s worth it because, for one, the truth is an absolute defense. And people don’t die in Myanmar because you got so big moving fast and breaking things that you can’t clean up after yourself anymore.

It took Sam a while to accept my decision. He was worried that my exit would affect his experience. I respect that very much. People with disabilities need help living lives that are more open and connected. He finds community activities through Facebook. Because he can scroll at his own pace, he can absorb and react to more news that people share. He’s not impervious to the third-party nonsense, but he’s not going to show up at a fake rally meant to destabilize the community.

I’ll still be on Twitter because I use the platform for my job and I can’t escape it. And I know my departure from Facebook may affect my coworkers, so I will work to ameliorate that. I hope that readers who want to continue to be part of Family Room will use the green button below to bookmark the blog and come back once a month or so. This blog isn’t going away even though the Facebook teasers will.

My first objective will be to use my words to be more open and connected. Family Room will be one place to make that happen, along with all of the other ways we’ve always had to connect with each other (insert mail-telephone-plus-ruby-slippers icons here!)

My second objective will be that when I have something to share, I will share it with the person I believe would appreciate it most.

My third objective will be actively listening to others in the coming days and weeks. Because the best way to connect is to respond.

Sam taught me that.

Other lessons stated out loud

“Our children are not us … and yet we are our children; the reality of being a parent never leaves those who have braved the metamorphosis.” – Andrew Solomon, Far From the Tree.

There are so many lessons from life with a child with autism, it seems important to share at least some of them.

I have two other children who make it into these pages in ancillary ways, but that is not an accurate reflection – at all – of their presence in our family.

Many things that happen in our lives are examined in thoughtful ways, but not everything that happens to our family gets lived out loud. I want my children to have their own lives.

For this little essay, I’m making an exception. Two years ago around Halloween, something happened to Michael that needs to be lived out loud.

He took a date to a costume party, and he’s alive today because technically he and the girl weren’t “dating.”

(Confession: I don’t understand kids and dating these days.)

He had graduated college earlier that year. His date was in her senior year, so the party they attended was full of college-aged kids.

As they were about to leave, someone handed his date a glass of champagne. She wasn’t a fan, so they shared it.

His date lived about 30 minutes out of town. A family friend happened to be at the party, so she rode home with him.

Michael hopped in his car and drove the 5-minute trip back to his apartment.

A minute or two after he got home, he knew he was in trouble. He stumbled to his room, vomited, passed out on his bed, and woke up at noon, although he was groggy and out of sorts all day.

His date, by the way, passed out on the way home. The family friend had to carry her to the house.

Michael didn’t tell me what had happened to them until weeks later.

The glass they shared, as near as he can guess, was laced with something meant to knock her out.

(Confession: I asked him the classic victim-blaming question, don’t you all know not to accept a drink like that, along with a thousand other questions that had few satisfying answers. It wasn’t hard to imagine a drastically different outcome had he driven his date home.)

This was not the first time something horrible happened to Michael and I was not to find out until hours after the real danger had passed.

That is how it is when you send your children out into the world.

It is not a good feeling.

Some of us parented our kids to know that life is not a stage and all the men and women in it merely players.

Clearly, some parents did not.