self-advocacy

Talk to yourself, and tap the ‘wisdom of the inner crowd’

Some years ago, I took a call at my desk in the newsroom from a woman with a news tip. The details of the tip escape me now, but her explanation stayed. She wanted us to understand why she was calling, because the situation suggested she’d been living a lie and she was making big changes. She told me that she had a growing interior life and she asked, didn’t we all? Yet her husband could not grasp the concept.

Although she made no reference to Christianity when we talked, this concept of an interior life has roots there. The idea is to have an ongoing conversation with God. By focusing on a friendly, internal exchange with your Creator, you can transform your actions into good works. The faithful call it “prayer.”

If you think about that for a minute, the word prayer can provide a powerful cover to these internal dialogues, especially when spoken aloud. (As does reading and writing, for that matter.) We need that cover because society tends to scorn (or worse) people who talk to themselves.

Now, science has discovered that it may be objectively helpful to talk to yourself. In the Wolfe house, we’ve tolerated thinking out loud. Over the years, we’ve learned to tolerate a range of human behaviors that we didn’t understand at first. Autism has often revealed our ignorance of behavior that is actually beneficial. So, we made room for the possibility that having conversations with yourself could be beneficial. To be sure, these internal-but-out-loud dialogues occur out of earshot of each other, although I still tend to direct my commentary to the dog, as long as I’m not confusing him.

The idea is that there could be wisdom in your “inner crowd.” There’s plenty of research into the wisdom of actual crowds. That research shows that when compiling diverse and independent opinions, they tend to average out, minimizing mistakes and revealing the truth. So, it doesn’t quite make sense that talking to yourself is going to expand your knowledge or change the internal biases that lead to mistakes.

However, some recent studies found that people can get closer to a good answer when they take another’s perspective. Researchers asked participants a factual question (such as the size or count of a thing), asking first for their own answer and then for an answer of someone who would disagree with them. In another study, researchers had participants outfitted for a virtual reality experience, one that contained an avatar of themselves and another Freud-looking avatar. The researchers prompted the participants to voice both avatars in a problem-solving conversation. They discovered that people were able to give themselves good advice.

The outcome reminded me of the power of social stories when Sam was a kid. The stories spelled out the social cues he otherwise missed. He always knew what the “answer” was. In other words, this idea may not be grounded in the principle of crowd-sourcing information at all. I think the idea is to create space. Talk out loud and you give yourself room to think and for all that inner wisdom to break through.

Here’s a couple resources to get you started talking to yourself:

Alter, Adam. (2023) Anatomy of a Breakthrough: How to Get Unstuck When it Matters Most. New York: Simon and Schuster.

https://behavioralscientist.org/tap-into-the-wisdom-of-your-inner-crowd/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9984468/pdf/41598_2023_Article_30599.pdf

Road trip

It took some time to notice, but both Sam and I agree the pandemic made our lives a little smaller.

Don’t get me wrong. There were things we did, things we neglected, routines we filled, habits we clung to, all that needed to change. And we stopped being busy for busy’s sake (what was that about?)

But ‘opting out’ also sets its own traps. A certain brittleness can settle in. We needed to stretch.

We’ve gone on cycling trips to help with that. Acadia National Park in 2021. Lake Champlain in 2022. But this year, we felt like we needed to nudge in another direction. After we were invited to a wedding in Phoenix, I got out the maps and started studying road trips. After all, Phoenix is just a few hours from California. As a good friend says, it’s just “map math.”

But I wasn’t planning a grand tour. This trip could reconnect us to our family’s origin story. Sam and his brother and sister were all born in Sacramento. Their father was principal tuba of the Sacramento Symphony until it went bankrupt. We lived there until Sam was 5 years old.

A road trip could help Sam see that he was a Californian and still belonged, if he wanted that option. We took the kids to California several times on summer trips. Sam went back to visit once on his own (his godparents live in Stockton) when he was in his 20s. But visiting a place for fun is different than visiting with an eye toward making a life there.

Many of us don’t always feel we have options and sometimes this seems more so for Sam. We planned this trip to explore his options,. The company he works for has a similar facility in Modesto. Touring the Modesto location could help him think about his future in new ways.

We had all the fun we could stay awake for in Phoenix, and headed out the next day. We took a nice, leisurely detour through Joshua Tree National Park (amazing!) and spent the night nearby.

Then the next day we headed to Modesto, stopping in Fresno. I suggested a stop at an underground garden. I thought it would be a world’s-largest-ball-of-twine-roadside-attraction type of stop, but it turned out to be a national landmark and completely charming.

The next day, we toured the Modesto facility and wouldn’t you know, Sam already knew some of the people working there. They didn’t have any openings right then, but that’s not how Sam thinks things through anyways.

In the month since, though, I’ve heard him say many, many times, “I have options now, Mom.”

Never, ever underestimate the power of a road trip.

See Sam Drive, EV edition

We had to get up early today to meet the man delivering Sam’s new car. He bought a 2018 Chevy Bolt from the Fort Collins, Colo., dealer where my brother-in-law works. Sam was so very patient. When his uncle mentioned they had two Bolts on the lot waiting for their recall work, Sam put $500 down. That was back in December 2021.

Sam has been driving a 2001 Toyota Corolla since he first learned to drive 15 years ago. He also bought that car from his Uncle Matt. We started talking about replacing the Corolla around 2018-19, but Sam moves slowly with these kinds of decisions. He went to the auto show at the State Fair with his brother and sat in a Chevy Bolt. He tentatively decided he would replace his car in 2020. Then the pandemic came and life slowed down so much. It bought him a lot more time to shop for a car, which was good, because Chevy needed time, too, to make those battery repairs.

He didn’t need much coaching through all of this, at least not from me. Matt may have had to work a little harder to make the sale and delivery, I certainly can’t speak for him. The only thing I really weighed in on was getting the car back to Texas. We talked about flying up to get the car and driving back, but once we crunched the numbers, shipping won out. He agreed to do it, since it was cheaper by about a factor of 10.

He still has a bit of a to-do list — insurance, Texas plates, toll tag, etc. I did write that up and put it on the fridge for him, so I suppose that’s coaching. And he’s going to reach out to other EV drivers for wisdom, since this car is several generations more sophisticated than either of the vehicles we currently drive.

Life really is so flipping complicated. I have little idea how I got through things the first time myself, although I do remember a habit in my 20s of calling my parents often and asking adulting questions. I do also prompt my other kids–probably more than they would like–with the preface of ‘let me tell you something I learned the hard way and save you some time/money/heartache.”

Have you ever thought about all the problems you solved in your 20s?

A rose behind a geofence is just a rose, fenced

The word geofence joined the English language in the mid-1990s. As I type the word “geofence”, Microsoft Word doesn’t correct my spelling—yet, chances are high that if I want to talk with Sam about geofencing, the first thing we would have to do is talk about the word’s definition in plain language.

Sam inspired me to become a plain language fan. It’s not just because we now have the Plain Writing Act of 2010, a federal law that sets the standards for certain government agencies to better communicate with people.

When talking with Sam in plain language, we usually find some great truths. We have to be thinking very clearly to boil stuff down to its essence. And then Sam, always a great thinker, figures out what that essence means and where that new essence belongs in his life.

So, the word “geofence” in plain language: A boundary line on your computer.

We sometimes say that good fences make good neighbors. The poet Robert Frost had more to say about that. In other words, a fence on a computer has meaning, too.

Our local transit agency, DCTA, experimented with a computer fence to offer van rides to the west side of town a few years ago. Sam used that van service to get to work a few times. It was very hard. I rode with him once. First, you had to travel to the fence line, then you could hail the van that only gave you rides inside the fence lines.

The day I went with him, I had to wait a half-hour to ride back to the other side of the fence. While waiting, I saw dozens of DCTA vans driving Peterbilt workers to destinations that I knew were traveling far beyond the fence lines I was traveling in.

Recently, our transit agency has drawn new fence lines for van rides. At first glance, the big pasture of service seems generous. But at the same time, they also cut most of the buses whose lines weren’t fences, but veins.

Suddenly, yet predictably, too many riders are coming from certain areas. DCTA says they may “geofence to manage demand.”

Or, in plain language: they will draw lines that push riders out.

Sam has told me more than once that he wants to ride bus to work. I began to doubt whether that would ever happen after I saw the long line of Peterbilt-subsidized DCTA vanpools. Then, when an apartment developer paid extra for DCTA to run a bus to its massive apartment complex adjacent to the warehouse district (beyond even the millions UNT pays DCTA to run buses), I gave up hope. We don’t, and probably won’t ever, have a system to serve the thousands of people like Sam, who can make their lives better with the mobility that connects them to economic opportunities–let alone the magical world that exists for all of us when our community has that kind of mobility.

Some politicians (and their constituents, of course) will always be attracted to lines like geofencing. Playground games follow the boundary lines. Winners and losers are determined by the lines. And, as we all know, some kids aren’t allowed inside the boundaries to play at all.

I doubt our transit agency board recognizes the deepest meaning of its actions as it draws these lines. The longer they allow those fence lines to exist on computers, the more those lines become real-life walls.

Reagan was wrong. There is no trust when you must verify.

The first time I took Sam to school and left him for a full day was a big leap of faith. I wasn’t alone, of course. Parents want to protect their kids. And parenting a child with autism or other disability puts that protective feeling into overdrive. Eventually I saw that we weren’t alone. His many teachers and therapists were part of his village. Later that year, I walked into a special education team meeting and recognized that, for the first time in Sam’s young life, I was not “on call” for every minute of every day. It was such a nice feeling, one that left room for more thinking and reflecting about our lives, and for resting, too.

That’s not to say that his school years were perfect. We knew not everyone in his life would be as mindful. But we also knew that the perfect is the enemy of the good. When conditions warranted, someone at school picked up the phone and told us about an emerging problem. We addressed many small things before they got big. And we learned to celebrate the average and the good enough, which was its own kind of achievement for Mark and me.

So (and you knew there was a so, didn’t you, dear internet people?), I struggle deeply with the burgeoning installment of security cameras at school. We aren’t just pointing cameras at the school’s exterior doors. Or in the hallways. Or from the school resource officer’s body armor. We are pointing them inside the classrooms, too.

In Texas, parents can ask for a camera in their child’s special education classroom. The school must get consent from parents of the other kids in the class, but such camera use is on the rise. Advocates for kids with disabilities continue to press the legislature for broadening a family’s rights to footage. One day, some parent will send their child with a disability to school with a body camera if they believe it’s necessary.

I recognize that school can be a rough place for children who don’t fit in for one arbitrary reason or another. Sam was getting hassled in the boys’ bathroom one year, and solving the problem proved tricky for the aides, both women. But we figured it out.

I recognize also that some schools are hard pressed to fill their teaching ranks. There are employees without enough skills to work with and manage kids, the place where most tragedies begin.

This is not to say that people in our community might have different values from my family’s or yours. As a culture, we wobble too much in figuring out how to work with those differences as strengths and educate our children. But I have to say, where parents are asking for cameras, we aren’t reading those huge warning flags.

When Sam graduated high school, I wanted everyone from elementary school on up to have a “Team Sam” button as a little token of our esteem and affection. I ordered 250 buttons and did not come close to gifting all those people who touched his life and helped him make progress. Dozens of teachers, of course, but also speech therapists who worked with him on communication skills. Occupational therapists and adaptive physical education teachers who helped him with his motor planning and ability to calm himself. School counselors who helped him build friendships. Aides who helped him stay on task in class and occasionally take a moment to decompress when he couldn’t. And the principals and other staff who stood by and made sure all those people had the support they needed.

I had to trust these people. All of them. A lot.

There was no “trust but verify.” Where there are cameras, there is no trust.

Small, little men

The national media is noting the ignorance and cruelty in Texas public policy, including the new laws that ban abortion and suppress voting rights. I would argue that the state’s policies and governance vis-à-vis people with disabilities amply demonstrates that this ignorance and cruelty isn’t new.

Elected officials in Texas have refused for years to adequately fund the medical and disability services that allow individuals to live in the community and avoid costly (especially to taxpayers) institutional care. Federal programs can pay the lion’s share of these services, and in most other states they do, but Texas refuses to expand Medicaid enough to allow that to happen. Instead, they authorize puny levels of funding for “waiver” programs—part of the federal law that allows Texas and other states to opt out with the promise to take care of people in their own way. But really what Texas does is pretend the burden doesn’t exist. Instead of fostering human progress, Texas disability policies hardwire families and communities for long-term suffering.

Sam was in kindergarten when we first moved to Texas. We followed the advice of the good people at Denton MHMR and put his name on one of the infamous waiting lists for the state’s waiver programs. Our social worker said that even though we couldn’t be sure then what services Sam might need when he was 18, we’d have no chance at help if he wasn’t on a waiting list. At the time, we were among the young families that got a little help paying for respite care and for special equipment, so we picked the waiting list for the waiver program most like that.

(Sadly, a year or two later, even that modest state program for young families ended. We were on our own.)

Families who are able to access services under these sparsely funded waiver programs understand them much better than I do. Sam made enough progress and adapted well enough that he doesn’t need the help—the kind of basic human need that tends to make allies and advocates into battle-hardened experts in the shortcomings of public policy.

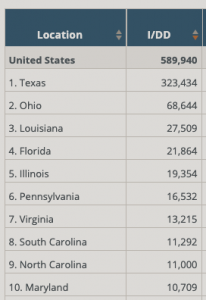

But I do know that the Texas waiting lists for waiver programs are cruelly long. Nationwide, there are about 600,000 people on a waiting list and more than half of them are on a list in Texas. (For context, remember that less than 9 percent of the nation’s population lives in Texas.)

In its latest budget, the Texas Legislature funded additional slots to get more people into the waiver programs, but not nearly enough. Some advocates and self-advocates have done the math: the Texas list is so long that individuals could wait their whole lives and never receive services.

When other states would get in this deep, they agreed to Medicaid expansion made possible by the Affordable Care Act. Waiting lists for waiver programs in those states nearly disappeared because Medicaid expansion stepped in to fund those services.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Texas is among just 12 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. Texas is, by far, the most populous state to refuse to provide services at a meaningful level and make no real progress toward that goal.

Some advocates wonder whether the U.S. Department of Justice will intervene, especially when U.S. Department of Health and Human Services officials seemed to wobble on approving the state’s waiver program earlier this year. It’s a great question, but we need look no further than the state’s troubled institutions—called state supported living centers—to see how a negotiated settlement might go. Independent federal monitors have visited those centers since 2009, after fresh reports of abuse and neglect emerged with cellphone video of a “fight club” forced on residents at the Corpus Christi center. All 13 centers were supposed to meet negotiated standards by 2014 or face further action, up to and including closure. Twelve years later, none of the centers (home to about 4,000 people with developmental disabilities) met the standards, the monitors still make regular visits, and all 13 centers remain open at increasingly unsustainable costs to state taxpayers.

Texas is growing fast and its people need a far more robust physical and social infrastructure than state officials seem to grasp. Some people see our governor moving about in a wheelchair and think he’s got the disability thing covered. But advocates know better. “He’s not one of us,” I heard one self-advocate say recently, pointing out the many, many differences between an individual who must adapt their entire life when compared to the governor’s experience, where the need for a wheelchair came much later in a life of privilege.

These days, Texans are watching their governor and the other small, little men in state leadership race to the bottom in a panic to maintain power. In that twisted race, their lawmaking and policies are displaying new levels of ignorance and cruelty for all to see. But color me not surprised, as the ignorance and cruelty has been part of their law- and policymaking for our community for a very long time.

Conservative guardianship

Britney Spears’s battle to be free of the conservatorship that has governed her affairs touches familiar themes for us old-timers in the disability world. She’s asking for the grown-up version of the least-restrictive environment, the federal right of children with disabilities to receive a free, public education alongside their peers in regular education classes, with support, if necessary.

For now, the least-restrictive environment is the best way we know to ensure every child has access to all they need to learn and grow into their best selves.

Over the years, I’ve seen a few families struggle to understand what guardianship really means. Adults need a least-restrictive environment, too. When Sam approached high school graduation, we were told that, as his parents, that we’d better think about setting up guardianship before he turned 18. It has been a few years now, and perhaps understanding has improved among the teams that do this transition planning, but at the time, Mark and I really thought that recommendation came out of left field. We’d fought for Sam his whole life for him to be included at school and in the community, to be in that least restrictive environment. Something about guardianship felt very restrictive to us.

Then an older, wiser friend boiled it down for us. “You’ll have to tell a judge, in front of Sam, that he’s incompetent.” I can still see Mark’s face when he realized what that meant. “We could never do that to Sam,” he’d said. To which I’d replied, “oh, hell no, we couldn’t.”

I often bring the salt, just FYI.

For our family, that ended the guardianship discussion right there. I did poke around a little, however, to figure out ways we could be his bumper guard. Once you start looking around, there are all kinds of ways to be there for someone, even in a somewhat official capacity, from bank signatories to putting both names on a vehicle title to advance directives and more–all without ever stepping foot in a probate court.

Last week, I learned even more about the power of supported decision making, an alternative to guardianship that gets you in the door when your loved one really needs you. These documents are legally recognized, even if your loved one is ensnared in the criminal justice system. One-page profiles can also help a lot for those times you can’t get in the door–when your loved one is in the hospital with covid, for example.

When your loved one truly needs a guardian, it pays to be thoughtful and as minimally restrictive as possible. That can be tough in Texas, just another FYI.

This year, advocates helped defeat a troubling bill filed in the Texas House of Representatives during the last regular session. If it had passed, the bill made it too easy for parents to get and retain guardianship of their teen. The legislation was inspired by one family’s tragedy, but it was rife with unintended consequences that would have stripped many young adults of their autonomy—especially if special education transition teams in Texas school districts are still advising parents to pursue guardianship without thinking it through.

Refrigerator Mother 2.0

Only a few generations ago, some doctors blamed mothers for their children’s autism. Psychologists wrote long theoretical papers based on their observations of mothers and their children. They concluded that autism mothers were cold and that their lack of love triggered the child’s autism.

If you stop to think about that idea for a minute, those explanations were quite a leap. And a cruel one at that.

We humans look for patterns in the world around us–it’s almost one of our super-powers. We use the information to make meaning, and create loops of ferocious thinking that make the world around us a little better.

Therefore, knowing that we’re supposed to make things better, the Refrigerator Mother explanation for autism just begs the question. How much did those early theoreticians consider and—most importantly, rule out—before concluding they’d observed a pattern of mothers who don’t love their children?

Granted, many people were immediately skeptical of these mother-blaming theories, including other professionals and autism families. The theories fell after a generation, but the damage was done to the families forced to live under that cloud as they raised their children.

And, the blame game is still out there.

The latest iteration has started in a similar way, with people seeing problematic patterns in autism treatment. Young adults with autism are finding their way in the world. Some of them had good support growing up, but the world isn’t ready for them. Some of them had inadequate support growing up, so they have an added burden as they make their way in a world that isn’t ready for them either. Some are speaking up not just about the world’s unreadiness but also about that burden. We must listen. Autistic voices can help us find new patterns and new meaning and build a better world for all of us.

We should be careful about letting one person’s experience and voice serve as the representation for the whole, because that’s how the blame game begins. Even back in the old days, when information was scarce, we had the memoirs of Temple Grandin, Sean Barron, and Donna Williams to show us how different the experiences can be. As Dr. Stephen Shore once said, if you’ve met one person with autism, then you’ve met one person with autism.

Here’s an example of how that can break down: some now argue that asking an autistic child to make eye contact, as a part of treatment service, is inherently abusive because eye contact feels bad for them. Missing from that argument is the basic context, the understanding that for humans to survive, we need to connect to one another. For most of us, eye contact is the fundamental way we begin to connect, from the very first time we hold and look at our new baby and our baby looks back at us.

I asked Sam recently (and for the first time) whether making eye contact is hard or painful for him. I told him I was especially curious now that eye contact changed for all of us after living behind face masks for a year. He said this, “Eye contact is very powerful. I wonder whether I make other people uncomfortable with eye contact.”

He’s right. It is powerful. And he just illustrated the point about one person’s perspective.

When Sam was young, we never forced him to look at us. But after a speech therapist suggested using sign language to boost his early communication, I found the sign for “pay attention” often helped us connect.

The additional movement of hands to face usually sparked him to turn his head or approach me or Mark in some way, so we were fairly sure we had his attention and that was enough to proceed with whatever was next. Over the years, we’ve shared eye contact in lots of conversations and tasks. But if not, we recognized the other ways that we were connecting and I didn’t worry about it.

All of this context—both the need to survive and the difficulty with a basic skill needed for that survival—cannot go missing from any conversation about the value of teaching an autistic child. Some people with autism do learn how to make eye contact early on and are fine with it. Some don’t. For this example, then, we can listen carefully to adults with autism and their advocates as they flag patterns from their bad experiences with learning to make eye contact and make changes. But that fundamental need to connect and share attention remains.

That’s when we also need to remember our tendency to blame others when our troubles feel intractable. Sometimes, in these fresh arguments over how autism treatment should proceed, I hear that same, tired pattern of blame I’ve heard since Sam was born. Take it from a worn-out mother who’s been blamed plenty over the years: some arguments are just another round of the same, they just come inside an elaborate wrapper of mother’s-helper blaming instead.

All the families I know truly love their children and are learning how best to respond to them. We can’t forget that parents have a responsibility to raise their child as best they can. Let’s talk, please. But please also, let’s spare the rollout of Refrigerator Mother 2.0, because it could cost us a generation of progress.

Take it to all four corners

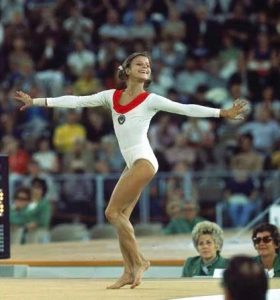

Olga Korbut changed the face of gymnastics when I was in junior high school. She looked so graceful and athletic in Seventeen magazine’s photos from her performance at the 1972 Olympics. As you might imagine, many of the wiggly tweens in my gym class were excited that our teacher added a gymnastics unit, largely because of what Korbut had inspired. Now, we could all experiment with moving through the world that way. That’s also when I learned one of the rules of floor exercise: a gymnastics routine can borrow from dance and mix in lots of tumbling, but it must also go to all four corners of the mat.

It’s a curious rule, yet wise when you think about it. It requires the competitor to be thorough as they challenge their body. I started thinking about that rule again recently and decided to add it to my ongoing pursuit of small, yet large, New Year’s resolutions. For 2021, I plan to take things to all four corners.

Last year’s resolution, Wear An Apron, feels prescient now, given the pandemic. We certainly spent a lot more time in the kitchen in 2020. But the bigger idea behind it–that whatever problem we faced, someone out there solved it already–kept us grounded, too. Online, we found Khan Academy to help Sam (and me) learn calculus as well as a sewing pattern and instructions for face masks vetted by some pragmatic nurses in Iowa. On YouTube, I started following a smart yoga instructor and my dad’s favorite backyard gardener, a fellow in England whose bona fides begin with his unapologetically dirty hands. Even streaming The Repair Shop revealed wide-ranging wisdom about problems I didn’t even know could be solved. Awesome.

Thinking ahead to this year, I remembered an editor who would remind us reporters to nail down all four corners of an investigative story before publication. Smart advice, but it also created a defensive image in my mind’s eye rather than something inspired by filling up the space of a gymnastics mat. Don’t get me wrong, it’s important to be able to rigorously defend your choices and actions, but the big idea for 2021 shouldn’t be about the pursuit of perfection. Instead, going to all four corners means planning thoroughly, and being careful and deliberate.

Raising kids, especially someone like Sam who needed so much, shunts the pursuit of perfection to the side in favor of steps that move toward progress. But I can’t say we always took it to all four corners.

For example, Sam does pretty well in the kitchen. All my children learned cooking and cleaning basics and food safety. Now, Sam does so well with some recipes that I can plan time off in the kitchen when he steps up. But I know we haven’t taken it to all four corners. Managing a kitchen is hard with all the planning and shopping. And the principles of cooking that let you tackle a new recipe, that’s something else, too.

So, not such a small idea after all. But it may be warranted for 2021, because I bet once we let loose the reins from the pandemic, there could be many things that need to be thought through again, and to all four corners.

Lessons of calculus

Sam didn’t learn calculus in high school and has decided, now that he’s in his 30s, that this deficit in his education must be remedied – not just for him, but for me, too.

I was a bit of a math whiz in junior high and high school, and while I didn’t get much calculus instruction either, I was somehow destined to review algebra, geometry, and trig lessons at least once a decade as the kids grew up and as Sam struggled with advanced algebra classes in junior college. To share in Sam’s enthusiasm for this new endeavor, I picked up Steven Strogatz’s book, Infinite Powers. It’s a persuasive little tome about the secrets of the universe and the author has nearly convinced me that God speaks in calculus. (And, perhaps that is why we have a hard time understanding Him.)

Sam doesn’t need all that. He just wants to master the principles and formulas (Hello, Kahn Academy) to break free of the limits he feels in his amateur music and sound studio, acquiring the demigod ability to manipulate the sound waves his computer produces.

Sam and I have been chipping away at this calculus thing for several weeks, beginning with a thorough review of the fundamentals. We know you can’t do the fancy moves until you’ve got the basic blocking and tackling down cold.

Through this journey, I’ve watched Sam learn a lot when we make mistakes. Kahn Academy tutorials ring a little bell and throw confetti every time you get an answer right. We don’t stop and think about how we nailed it. However, get the answer wrong and we are motivated to go back to find the missteps. Somehow, examining that failure locks in the learning just a little deeper.

Some writers and thinkers dismiss the fandom that failure gets in the business community. (Failing Forward! How to Fail like a Boss!) They are right: platitudes can’t turn failing into big money and success. That whole ready-shoot-aim philosophy just gets you muscle memory for ready-shoot-aim, in my experience. Examining your choices and, importantly, your knowledge deficits before making changes is what gets you back on the path of progress.

When I was in graduate school at the Eastman School of Music, some of us sat for a short, informative lecture from brain researchers at the Strong Memorial Hospital (both the school and the hospital are part of the University of Rochester). They showed us how the brain looks for motor patterns in the things that we do (walking, for example) and then files those patterns with the brain stem once established. It makes our learning and doing more efficient. But, of course, for practicing musicians, that tendency is a terrifying prospect. Practice a music passage wrong often enough and your non-judgmental brain says, “Aha! Pattern!” and files it away for safekeeping. The last thing you want is for that incorrect pattern to trot itself out when you are stressing. That’s how mistakes happen in a big performance. And they do. All. The. Time.

Sam and I are doing our best to go slowly and learn how to work the principles and formulas right the first time, or at least going back to retrace our steps when we trip up so we walk it through correctly on the second pass.

We’re learning calculus, the secret of the universe.