Writing

The ‘many-wrongs’ principle

Yesterday, I called my old friend, Donna, to catch up. Soon I was bouncing an idea off her. She’s smart, and instantly finds the holes when thinking or writing about something. I told her I’d been reading the research literature on social networks and stumbled across the idea of the ‘many-wrongs’ principle.

If there’s an idea that gives you permission to be wrong, and for everyone around you to be wrong, well, I couldn’t pass that by. Donna agreed.

It took awhile to piece together the research that lead to this particular paper. But, while combing through citations, I found a webpage that introduced the ‘many-wrongs’ principle to triathletes. This was getting exciting, albeit in utterly nerdy way.

I finally laid my hands on the origin story. In the mid-1960s, zoologists in Finland used radar images and film to painstakingly trace the migration of certain ducks. From what they knew about the individual talents of the birds, they couldn’t explain how they replicated their flight path each season–especially when considering storms, winds, fog and topography. Yet, they proved that, when traveling in large flocks, the ducks flew nearly the same path every year, differing only by a degree or two each time. Other scientists recognized their discovery. They called it the “many-wrongs” principle.

The idea was exciting, but scientists had to abandon the line of inquiry because they didn’t have the technology to do it. Hand-tracing flight patterns from film and radar images couldn’t be that technology.

Decades went by. The idea was almost lost to time. Research into bird migration continued and then stalled. Scientists knew a lot more about the vagaries of migration and the individual capabilities of birds, for example:

“geomagnetic compass precision is reduced near the equator and the poles; stellar rotational cues are unavailable for much of the year in the polar regions; solar cues vary with season and location; navigational errors can be compounded by wind drift; correctional mechanisms can reduce directional bias but add their own random errors. Even if orientation cues were absolutely reliable, flawless navigation would require perfect sensory interpretation and integration of cues by individual [birds].”

But they were farther than ever from answering the question. How did birds migrate with such precision? Another scientist unearthed the old idea. He argued it was time to figure out how many wrongs could make it right.

Soon, other researchers were working on the math, and thus the robustness, of the principle. (As I have argued in this space before, the universe speaks in calculus.) Their study used simulations of people randomly walking from one point to another.

The magic measurement was a radius for the behaviors that suppress individual error in group cohesion. There was a radius for “collision avoidance”, and one for “orientation interaction” and another for “group cohesion” – thus the influence of your neighbor. There were no “leaders” or “more experienced navigators,” even though it is possible to model the following of experienced navigators and it is known to happen.

Renewed interest in the many-wrongs principle has fed new discoveries, including the understanding that humans also tend to navigate better in groups. Triathletes will swim with the group to improve their navigation in the open-water leg of the competition. When survival is the goal, there is intelligence in the tactic that you select.

Researchers also found that when the environment is turbulent, there seems to be no benefit in staying with the group. It’s logical that when conditions are turbulent, it’s going impair a group’s cohesion. But it’s also really sad. That’s when I realized this principle is also one of poetry.

Right now, our path is unmarked and unclear. But we’ve also been here before. Nature is our best guide when we watch carefully and follow her principles. Many-wrongs requires only that we come together to move in the direction we want to go.

Don’t sand down a square peg and call it support

For the past several months, I’ve been reading the research on adults with autism. The work should help me prepare for the next book but, more importantly, help me do a little better in this current chapter of life.

In surveys of the research literature on adults with autism, several authors say there’s not much out there. There was even less research 20 years ago, so I’m not beating myself up for being late to this party.

When Sam was a toddler, I emptied library shelves, checking out books, looking for answers. Back then, autism research had barely exited the blame-the-mother stage and was focusing on young children. I found Maria Montessori’s original treatises and other general child development research and writings the most helpful. Over the years, I believe that concept—looking first to the big, fundamental ideas and then to the science that follows—has worked well for our family, which feels forever on the front lines.

For example, a recent study set out to create a sturdy vocational index for adults with autism. Why do we need such a thing? The researchers’ answers had a lot to do with shoring up future research and policymaking. But for the rest of us, who are watching our loved ones and their peers go after their employment and higher education goals right now, it can still help to be precise in describing current conditions and supports.

After all, the first step in solving a problem is identifying what it is.

In this particular study, the vocational index would score Sam’s work conditions and supports at the top, since he works full-time with the same support as any other warehouse employee. The index would score the work conditions and support of another young man we know just a little lower, because his work was part-time and he had additional support from a job coach.

That differentiation is a small step forward, but the rest of this young man’s story shows it also has its limits.

Like Sam, he has autism. Until recently, he was working on the retail floor at a pharmacy.

The pharmacy, which is part of a national chain, is participating in one of the state’s workforce programs. In addition, a former special education teacher served as his job coach. In the end, the job didn’t work out, and I’ll bet you, dear reader, already know why.

His family recognized something off in the support he was getting, but it wasn’t readily apparent what was wrong. After all, someone was there, someone whose job was to help him.

Ultimately, the job coach was meeting the pharmacy’s needs first, not the employee’s. The company needed workers. Joining the state’s workforce program allowed the company to tap a new pool of workers with little risk or investment on its part. And that showed.

As a former special education teacher, the job coach should know that a robust assessment of the worker’s skills and the workplace conditions comes first. Just based on our early experiences, I’ve got a pretty good idea how perfunctory that fellow’s assessment probably was. Sam’s first job placement was sacking groceries because that was all the state’s workforce program had to offer. They honestly didn’t look too hard at whether the job was a good fit.

It was clear that the pharmacy wrote up a task list long before any potential employee came through the program with their own strengths and skills to offer the store. Unsurprisingly, it can be a lot to ask some individuals with autism to respond to the shopping public. Sam says he couldn’t imagine doing it today. Some customers were already awful when he was sacking groceries years ago, and these days, there seem to be more awful customers and some just go off the rails with their complaints. So when this fellow’s job coach decided that he needed to pause the program and get some behavioral training instead, it was clear something else had gone off the rails.

This young man sometimes answers questions in long-winded ways, and some of the pharmacy staff and the customers didn’t like it. The coach didn’t either. We’ve all heard about the square peg that doesn’t fit in a round hole. We know the answer isn’t to send the peg out for sanding down, and down, and down. But that’s what was passing for job support for this fellow.

So the next question has to be, how do we measure support in the index, or how do we make sure what’s passing for support is actually support?

New year, new book?

If declaring a New Year’s resolution out loud helps you be accountable for it, I’m here for it, dear readers. About half way through the book I co-wrote with Shahla, I recognized the need for a book for parents of adults with disabilities. A book about transition.

For parents sending their grown child with a disability out into the world, the word “transition” has become the shorthand for this journey. The word is both dead-on accurate and completely wrong.

Most families start planning for transition long before a high school graduation. There is a lot to think about. What’s next—a workshop, job placement, vocational training, college? Where will they live? How can we find adult health care providers to replace the pediatric team? What other services will they need as an adult? Where will the money come from?

All these questions deserve answers, even though the resources needed to support choices and pursue dreams after high school are often different than those available in school. If those resources even exist. Many families describe transition planning as going off a cliff.

Our family’s journey felt like that sometimes. But the more I tried to think about transition as a journey, the more it felt like we could build resilience.

Sam says his New Year’s resolution this year will be building resilience. I think he understands where we are now and where he wants the path to go.

Sam and other young adults with disabilities deserve to be surrounded by people who respect and honor their agency and humanity, no matter what long-term supports they need.

The truth is, we all need support of one kind or another, especially as we age. Some support flows readily from modern life—grocery delivery, cleaning services, public transit. Other connections can be elusive—meaningful friendships, helpful neighbors, extended family relationships. Yet we know that any community can grow stronger when each and every person makes their full contribution to its betterment. That’s where resilience comes from.

That will be the purpose of this new book, harnessing the “big ideas” families need to make transition feel less like going off cliff and more like taking flight.

Oh, and my other resolution will be to finally learn how to make pie crust. Tips welcome.

Dad

My dad died Sunday.

It was so hard to let him go. He had three wishes: to die at home, to have no service, and to leave his body to the medical school. Those are tough promises to keep, but we did it.

A good friend told me a few months back that it would probably fall to me to write the obituary and I knew she was right. I penciled out his biography. Once in a while, I’d ask him a question or I’d listen carefully as he told someone a story. Bits and pieces got folded into his biography until all that was needed was the top and bottom that make it into an obituary.

Except that, as I’ve learned through the years as a reporter, a person’s family might know them, but they may not know the C.V. After several rounds of family edits, this was the final cut:

Donald Eugene Heinkel, longtime Windsor resident and devoted family man, died September 10. He was 88.

He was born April 20, 1935, in Cedarburg, Wisconsin, to Gerald Heinkel and Leocadia (nee Schesta) Heinkel, the second of five children. Although the family eventually settled in Rockford, Illinois, a large polio outbreak that began in 1937 in Chicago and northern Illinois sent him, along with his mother and siblings, to live near family in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, a tiny town on the western shores of Lake Michigan.

After he graduated high school and completed one year of college, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He was stationed in Japan following the Korean War. When it was time to return stateside, he asked his commanding officer to sail home, since he had been on shore duty in Japan. He boarded the USS Yorktown and finished his tour of duty on the USS Midway where he worked filing weather reports.

He took advantage of the G.I. Bill to enroll at Marquette University. He met his wife, Carol, while driving for a laundry service where she also worked. They married November 7, 1959. He earned both a bachelor’s and master’s of science degrees in biology at Marquette.

He then worked for two years as research technician. After realizing he’d be working from grant to grant, he went back to Marquette to enroll in dental school. In his final year of studies, he saw a notecard on a bulletin board. A small farming town in central Wisconsin needed a dentist. In 1970, the family moved to New London and he opened his practice on the second floor of a medical building. The practice grew and he moved to a spacious office building on the banks of the Embarrass River.

The central Wisconsin winters eventually proved too harsh. In 1978, he brought his family to Windsor, Colorado, where he bought an historic building on Fifth Street and did much of the rehabilitation work himself before opening a new practice to serve the fast-growing community.

A skillful woodworker, his first project—a lamp base that he couldn’t quite make square in 7th grade shop class—belied the artist within. As an adult, he took woodworking classes. In the first class, he built a twin bed that nearly every family member has slept in at some point, until he finally kept the bed for himself. His skill and creativity blossomed as he built furniture and decorative items from both classic patterns and his own designs, including tiny end tables assembled from scraps of Texas mesquite.

The move to Colorado also gave him a chance to join with other actors to form the Windsor Community Playhouse. He enjoyed playing a wide range of characters, from the terrifying and murderous Waldo Lydecker in Laura to the hilarious, hapless Father Virgil in Nunsense.

He sold the dental practice to Patrick Weakland and went to Saudi Arabia to practice for several years so that he and Carol could travel and then retire.

He taught himself to play guitar, and was an enthusiastic and accomplished golfer. He hit three holes-in-one during his amateur career, including sinking the same hole twice at Highland Hills and another during tournament play at Pelican Lakes. He also traveled to Scotland to play a round at St. Andrews, the home of golf, and to Augusta, Georgia, to volunteer at the Masters Tournament.

He was preceded in death by his parents; his brothers, Richard Heinkel and Dennis Heinkel; one nephew and one son-in-law. He is survived by his wife of 63 years, Carol; four daughters, Peggy, Chris, Karen and Teresa; three sons-in-law; five grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; four step-grandchildren and their six children; his sisters, Mary Ann Scott, of Arizona, and Helena Wagner, of Hawaii; and sixteen nieces and nephews, more or less.

The family is deeply grateful for the help of Dr. Douglas Kemme, Dr. Daniel Pollyea at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz Medical Campus, the Colorado State Anatomical Board, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the caring staff of Pathways of Northern Colorado and Homewatch Caregivers.

Adamson Life Celebration Home is in charge of arrangements. No service is planned. Donations may be made to the above organizations or to the charity of your choice. Or, in lieu of donations, make a toast to Don at the 19th hole.

Some bits and pieces from his biography ended up on the cutting room floor.

For example, the family didn’t want to emphasize his military service, because he saw that as a duty. No fanfare required.

In working other obituaries for the newspaper, I’ve sensed that when an individual leaves home–whether they enlisted, or entered college, or started their first full-time job–you often get a glimpse into their origin story.

At one point, my cousin got Dad talking about basic training in the Navy. Dad’s assigned spot for morning calisthenics landed him right in front of the drill sargeant. After the first day, he knew no good would come of it. Meanwhile, he was also offered a menial assignment. There were several bulletin boards around the base where posters and announcements needed to be swapped out and updated daily. Dad accepted the job. He said he knew it was a 20-minute chore, but he always made sure it lasted an hour or two, to spare him the morning calisthenics.

He told us more than once that he and a buddy went to the top of Mount Fuji. Finally, I got him to share details. They rode the train up. It was spectacular. When it was time to go home, they got on the wrong train down. The east side train had wayfinding signs in Japanese and English, to help the tourists. The west side did not. He and his buddy knew they were cutting it close. But they figured their way out and got back to base before they were awol.

I love those stories. They say so much about my dad. He was in the first year of a seminary college when he dropped out to enlist. What an incredible pivot, especially when you consider that the Korean War had just ended.

His life is full of these leap-and-the-net-will-appear moments. Growing up, I didn’t see him that way. But that’s the limit of your kid vision. Your dad is just always just there, punching the clock, supporting the family. Thank goodness we had the gift of time so all that richness could come through.

Being there, being present has incredible value, too. After Mark died, Dad was a touchstone for my kids. Sam adored his grandpa, and their weekly zoom chats. Family has helped him, and so have friends these past few days. His Born 2 Be friends at the riding stables have surrounded him. I’m grateful for our little village here. If you are so inclined, please consider Born 2 Be, and in my dad’s memory, during North Texas Giving Day.

Fledging

Late last week, walking with Fang, we came upon a red-shouldered hawk that had just made a kill near Rayzor Ranch Park. She was standing in a field with the varmint in her talons. The varmint seemed a little too silky brown and big to be a rabbit. There are a few jackrabbits in what is left of the old Rayzor Ranch. Or it could’ve been a nutria from the nearby retention pond.

I have seen this a few times before, this waiting after a kill. Once, a hawk had landed on a rat running in our postage stamp of a backyard in California. We watched through the dining room window as the hawk waited patiently until it was safe to fly off with her prey.

But this time, a scissor tail from the park decided there was no room in the new ‘hood for a hawk. I watched in wonder as the scissor tail dove for the hawk’s back, triggering the raptor to drop its prey and lift off. The scissor tail rode on that hawk’s back for a few hundred yards before veering off and back to the park.

I knew why she was doing that. A few days before, we were walking to that park (Fang likes Rayzor Ranch Park a lot.) At one point, I was almost face to face with a pair of scissor tails fledging their young — three little guys who didn’t have their scissor feathers yet, but were flying pretty well. They had just regrouped in one of the younger trees in the park, so they were barely hidden. The parents had tucked wings and tail feathers around them, as they all wiggled and peeped and got ready to fly again. We caught up with them a second time not far away, all three fledglings perched on a fence, side by side, peeping and wiggling and trying to decide whether Fang and I warranted another flight attempt as their parents flew overhead.

The sight of it all triggered a fast rewind in my brain, other times we’ve stumbled on fledging as we’ve walked. Once in a neighborhood to the east, a fledgling raptor had to be nearby–although I never saw it–because a Mississippi kite grazed me three times until we finally went around a corner. (I was so glad to be wearing a sturdy hat.)

Another time, I saw a pair of mourning doves standing unusually close to one another, perched on the next-door neighbor’s roof. I looked around and saw the fledgling in the gutter. The little guy wasn’t going to make it. I scooped up its body the next day.

Another time I didn’t see the fledgling until just after Fang spotted it hopping in the leaf litter beneath the oaks in McKenna Park. First the momma robin dove at Fang, and then the poppa. Fang immediately lost interest in the fledgling and was already crying uncle. But a call went out anyways and within seconds, every robin in the park was diving at the two of us, like a Hitchcock horror movie.

I got curious about how much scientists know about fledging and bird behavior. We don’t know a whole lot. I found a research study from 2018. This study suggested to researchers that fledging is negotiated between the young and the parents, with different species tolerating longer stays than others. Young birds that leave before they can fly very well have a higher mortality rate, of course. The scissor tails certainly had to fledge before their tails got too long, as my own mother adeptly noted. But the young that stay too long risk discovery by predators who bring jeopardy to the entire nest, parents included.

I’m not sure how well we humans do at fledging. Actually, in terms of survival of the human race, rather poorly, I think. We understand child development a little better than adult development. New research suggests a stage of emerging adulthood that warrants our closer attention. And, as most of us disability parents will tell you, fledging a child with a disability is tough. We have organized our culture in ways that discourage cooperation and care for one another, unless doing it for money. Can you imagine being like a robin and joining the entire flock to defend someone else’s child? We are too fond of gaming the economic rules so that one group or another gains an edge, instead of raising all boats. We do this change-up so often that it’s hard even for kids without disabilities to launch.

Maybe there’s a reason we know we are doomed. Maybe there are lessons from nature. Before it’s too late.

Restraints destroy relationships

To help promote the new book, I’ve been pitching op-ed pieces to newspapers. It’s interesting to be on the other side of the pitch. It also makes me miss Mike Trimble, my old friend who was the Denton Record-Chronicle‘s prize-winning opinion page editor, even more. I just miss him too much to imagine what he would say about my writing, but I try. After a few missed pitches, I asked more writing friends for feedback and that seemed to make a difference. The San Antonio Express-News recently published this piece on “restraints” which could see reforms from the Texas Legislature this year.

I think Mike would agree that the word “restraint” is a horrible euphemism for the things that Texas school and institutional personnel can do to a person with a disability in crisis, or simply to make them more easy to manage. Actions that, if a parent took them, would likely trigger an abuse investigation.

I was a little disappointed that the San Antonio editors cut so much of my original text, including the key phrase, ‘restraints destroy relationships.’ I guess it’s too scary.

Here is the full text:

When a parent first learns their child has autism, you can almost see the worry lines etch their face in real time. Their road ahead has changed. They need a new map. They will also need an experienced guide or two.

And those worry lines will deepen fast if they live in Texas, where school officials can still restrain children in ways that parents cannot, where there are caps on insurance coverage, and where the waiting list for adult services lasts for decades.

As with anyone, an autism family can thrive depending on how well the community responds.

A few generations ago, doctors told parents to send their child with autism to an institution and never look back. Today we know that autistic children can learn. New scientific knowledge and therapeutic practices are helping children learn to eat, talk, use the toilet, and master other life-changing skills. In addition, the first generations of children who benefitted from that new knowledge and practice are adults now. Some say that the early intervention changed the possibilities for their life—doing meaningful work, raising their own families, participating in community life. That was certainly the case for our family.

Other autistic adults say that their individual treatment program was abusive and traumatic. We are learning that some practices can be harmful, particularly those that focus on getting a child to comply with social ideals. This nature-and-nurture debate can be confusing for families new to the diagnosis. Parents want to raise their child as best they can, and for many autism families, the responsibilities don’t end in adulthood. Our society has built-in expectations and vulnerabilities that can create more frustration than support. The way each of us responds to an autistic individual can hinder the possibilities for their life—no different from the effects of buildings without ramps, movies without captions, or busy intersections without audio cues. It’s on us, as a society, to recognize that autism comes with its own gifts and strengths, and to respond accordingly.

How can we do that? It turns out that the basic principles for creating a healthy community still apply: by learning, connecting and loving.

Learning is fundamental to raising any child, but takes on special meaning for everyone involved in an autistic child’s life. Our learning begins not just with understanding each child but also understanding the science of learning itself—something our society often does poorly. Science tends to be a slow, deliberative process. Science doesn’t offer fixed answers to problems, in part because change and experimentation are fundamental to science. The same is true for human thriving, especially for children. We all need room to grow, change and develop.

Connecting to one another can make a difference, too. We connect when we respond to one another in meaningful ways and make sure that everyone, including each child, has agreed to whatever work we are doing together. This also means we have a duty to watch for poor conditions and change them. For example, Texas must change the conditions—and the laws—that allow preschoolers with autism to be strapped to chairs for their school day or a young autistic child in crisis to be placed in handcuffs. Research tells us that we don’t need to restrain children for them to learn. Moreover, the way we connect and respond to children, especially vulnerable children, has profound meaning. Restraints destroy relationships.

With love as their superpower, parents can meet their responsibilities to their children, even when those responsibilities are formidable. We can create the same animating force in a healthy society when we champion every child’s agency and ways to include them in the entire community. When we step up to serve as collaborators, scouts or vanguards for the families around us, we help our entire community make progress.

We humans need both science and inspiration to create the possibilities for our long-term well-being. When we all keep learning, connecting, and loving, we can build a sturdy, sustainable community filled with places and paths for every member of our community, no matter their gifts and strengths.

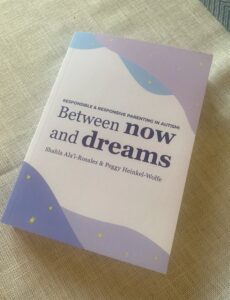

Ways to buy Responsible and Responsive Parenting: Between Now and Dreams + Bonus Materials

Ways to buy the book

- Order paperback from Different Roads to Learning

- Order ebook from Different Roads to Learning

- Order paperback on Amazon

- Order Kindle version on Amazon

- Or, buy an autographed copy from Patchouli Joe’s in Denton

- Audiobook coming soon!

**Click here for bonus materials for parents, clinicians and the media**

Reciprocity

Hello, dear internet people! Are you ready for another excerpt from the new book? In Part Two: The Power of Connecting in Between Now and Dreams (pre-order here!), Shahla and I describe what it means for parents to connect to others as they nurture their children. When we connect to one another, we foster our shared growth and we strengthen the beautiful ways we can respond to our child. All kinds of people bring energy and wisdom to this journey — friends, family members, neighbors, professionals.

We were particularly inspired by the woman who cut Sam’s hair when he was in elementary and middle school. Connie taught us all a great lesson about reciprocity in relationships.

Edited excerpt below:

Reciprocity, the ways in which we demonstrate our care for one another and influence and depend on one another, breathes life and depth into our relationships. Mutual dependence is part of the human experience. The most meaningful relationships might start by attending the same class, then remembering birthdays or taking turns buying lunch, eventually deepening over the years by sharing child care or stepping in when someone starts cancer treatment. Reciprocal interactions with family and friends not only nourish our lives but can also help our autistic child by creating healthy and natural dependencies that bring progress in a sustainable way. When we understand and value reciprocity, we can boost its practice and our family’s quality of life.

Consider how young children learn to play together, for example. A child without autism approaches another child at preschool who is playing with cars, but just by watching the action at first. Then, the child picks up another car and begins playing along. After a minute or so, the two children create together an imaginary scenario for the cars. The play then becomes a learning, rewarding experience for both of them. That is one key of reciprocity—it is founded on mutual reinforcement. Each person receives some benefit in the relationship. The benefit may be transactional, meaning that something immediate happens that both parties value. The benefit can also be relational, meaning that things happen over time that are important to both individuals, and the value occurs when they are together. Reciprocity also involves coordinated and shared attention. Each person finds happiness in the other person’s happiness.

Many of us, including our children with autism, struggle with reciprocity, especially in the beginning. We are all in the process of learning about reciprocity in our own growth and development. Consider the circles of people around us who make our life better and help further our understanding. For most of us, family and close friends make up the inner circle. Groups of friends from spiritual communities, social clubs, or sporting activities are in the middle. The outer circle is filled with our acquaintances and professionals, such as our barber, school counselor, or family doctor.

Michael Ball, an elementary school guidance counselor in Texas, thought a lot about the friendship circles among the schoolchildren. The students with disabilities, he knew, would have a hard time developing friends for their inner circle from that middle circle of friendships. To change that environment, he created many circles of friends, inviting a student with a disability into his classroom once a week along with several children without a disability to spend time together. He offered the circle of friends an activity they would all enjoy. He was careful to pick something the child with a disability could do with some success, yet something all the children would enjoy doing or playing. Then, he’d let things unfold, working with them to solve problems along the way, if needed.

Children with autism often need coaching or other guided practice to take part in basic reciprocal social interactions, such as playing with siblings at home, with friends on the playground, or at a birthday party. Other children with autism may only need priming or a special script that details what happens and how best to respond to basic social cues. Some children may also need to expand their interests so they have more to share and can find common ground with family and friends.

We can be on the lookout for interactions, large and small, that take advantage of the power of reciprocity to build our child’s world. Our child’s ability to move through these moments brings its own kind of mastery. That’s one reason that therapists work hard to teach very young children with autism how to imitate other people. Once our child can imitate others in different ways and situations, they are better equipped to learn many more things and faster. Their ability to learn and master new things can become so powerful that some structured teaching becomes obsolete for them, and reciprocity fills the gap. Reciprocity gives us access to new relationships. It’s like the difference for all of us after we learned to read—then we read to learn. We enjoy reading, too. We access new worlds when we read.

These big moments don’t stop in childhood. In their paper on behavioral cusps and person-centered interventions, Garnett Smith and colleagues described Sarah, who was twenty-two. Sarah’s grandparents were concerned that she was a homebody. She enjoyed watching college basketball on television. Her grandparents took a chance and encouraged a friend to take Sarah to a game. She enjoyed herself so much that she continued attending games and other large events. Her reciprocal interactions with other people increased exponentially. She talked with workers at the concession stand and with the players after the game. She participated in halftime activities. Her world expanded. In fact, Sarah developed a whole new set of social skills around the experience, a classic example of a behavioral cusp. She was much less of a homebody. She even asked her grandparents to go to other sporting events.

We can be on the lookout, then, for activities that capture reciprocal contingencies. Our child can join other family members preparing the table for a meal. They can take turns playing a board game with a sibling. They can write thank-you notes. In this way, everyone can be our child’s ally. Life is filled with many gentle back-and-forth interactions, all worth fostering because they make life better and have the potential to create their own sustaining energy for our child’s progress.

For example, Peggy’s son, Sam, couldn’t tolerate haircuts when he was a toddler. Peggy resorted to cutting his hair while he slept. It worked well enough, but when her next-door neighbor, Judy, a stylist, heard how they were coping, she offered to help. Judy brought her supplies to the house. Sam sat in the high chair in front of a full-length mirror in the living room. Sam told Judy how to hold his hair as she cut it. She was patient and went along with his directions, and still managed to cut it well.

When the family moved, Peggy wondered whether she would have to find someone willing to make house calls, like Judy did. She found another stylist. Connie had a big heart and boundless sense of humor. She kept Sam looking good from boyhood trims through the high school trends.

The whole family got their haircuts on the same day. Connie would ask Sam’s advice, who was next in the chair, and everyone conferred on the plans. As he got older, Sam stopped telling Connie how to hold his hair and let her cut it as she would for any client. Then, the conversation became whatever Sam or Connie wanted to talk about. Getting haircuts became a powerful lesson in reciprocity. Judy opened the door, and Connie showed how reciprocity builds those connections. She understood that the circle of what is given and received grows wider with the years.

Then Connie got cancer. Sam understood that she became too weak to stand all day and cut people’s hair. He found another barber. The relationships, begun by the simple act of cutting Sam’s hair, had brought out the best in everyone. When Connie died a year later, Sam and the rest of the family felt the loss of a friend. They still miss her.

Joy

Joy gives us wings! ― Abdul-Baha

Review copies of the new book I co-wrote with Shahla arrived on Saturday. It’s such a pretty little thing. All that warmth and wisdom on the cover is on the inside, too. And so is some really smart science. The release date is April 2. You can pre-order here.

A while back, the publisher shared an excerpt on their blog. I’ve included it below, editor’s note and all. It’s from Part Three: The Power of Loving. And it’s called Joy.

Editor’s note: Autism Awareness month is becoming a call to action from the autism and neurodivergent communities for change from the rest of society. In this edited excerpt from their upcoming book with Different Roads, co-authors Shahla Ala’i-Rosales and Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe offer a specific call to action to both parents and professionals—to seek and maintain joy’s radiating energy in our relationships with our children.

Parents have the responsibility of raising their children with autism the best they can. This journey is part of how we all develop as humans—nurturing children in ways that honor their humanity and invite full, rich lives. Ala’i-Rosales and Heinkel-Wolfe’s upcoming book offers a roadmap for a joyful and sustainable parenting journey. The heart of this journey relies on learning, connecting, and loving. Each power informs the other and each amplifies the other. And each power is essential for meaningful and courageous parenting.

Ala’i-Rosales is a researcher, clinician, and associate professor of applied behavior analysis at the University of North Texas. Heinkel-Wolfe is a journalist and parent of an adult son with autism.

“Up, up and awaaay!” all three family members said at once, laughing. A young boy’s mother bent over and pulled her toddler close to her feet, tucking her hands under his arms and around his torso. She looked up toward her husband and the camera, broke into a grin, and turned back to look at her son. “Ready?” she said, smiling eagerly. The boy looked up at her, saying “Up . . .” Then he, too, looked up at the camera toward his father before looking back up at his mother to say his version of “away.” She squealed with satisfaction at his words and his gaze, swinging him back and forth under the protection of her long legs and out into the space of the family kitchen. The little boy had the lopsided grin kids often get when they are proud of something they did and know everyone else is, too. The father cheered from behind the camera. As his mother set him back on the floor to start another round, the little boy clapped his hands. This was a fun game.

One might think that the important thing about this moment was the boy’s talking (it was), or him engaging in shared attention with both his mom and dad (it was), or his mom learning when to help him with prompts and how to fade and let him fly on his own (it was), or his parents learning how to break up activities so they will be reinforcing and encourage happy progress (it was) or his parents taking video clips so that they could analyze them to see how they could do things better (it was) or that his family was in such a sweet and collaborative relationship with his intervention team that they wanted to share their progress (it was). Each one of those things is important and together, synergistically, they achieved the ultimate importance: they were happy together.

Shahla has seen many short, joyful home videos from the families she’s worked with over the years. On first viewing, these happy moments look almost magical. And they are, but that joyful magic comes with planning and purpose. Parents and professionals can learn how to approach relationships with their autistic child with intention. Children should, and can, make happy progress across all the places they live, learn, and play–home, school, and clinic. It is often helpful for families and professionals to make short videos of such moments and interactions across places. Back in the clinic or at home, they watch the clips together to talk about what the videos show and discuss what they mean and how the information can give direction. Joyful moments go by fast. Video clips can help us observe all the little things that are happening so we can find ways to expand the moments and the joy.

Let’s imagine another moment. A father and his preschooler are roughhousing on the floor with an oversized pillow. The father raises the pillow high above his head and says “Pop!” To the boy’s laughter and delight, his father drops the pillow on top of him and gently wiggles it as the little boy rolls from side to side. After a few rounds, father raises the pillow and looks at his son expectantly. The boy looks up at his father to say “Pop!” Down comes the wiggly pillow. They continue the game until the father gets a little winded. After all, it is a big pillow. He sits back on his knees for a moment, breathing heavily, but smiling and laughing. He asks his son if he is getting tired. But the boy rolls back over to look up at his dad again, still smiling and points to the pillow with eyebrows raised. Father recovers his energy as quickly as he can. The son has learned new sounds, and the father has learned a game that has motivated his child and how to time the learning. They are both having fun.

The father learned that this game not only encourages his child’s vocal speech but it was also one of the first times his child persisted to keep their interaction going. Their time together was becoming emotionally valuable. The father was learning how to arrange happy activities so that the two of them could move together in harmony. He learned the principles of responding to him with help from the team. He knew how to approach his son with kindness and how to encourage his son’s approach to him and how to keep that momentum going. He understood the importance of his son’s assent in whatever activity they did together. He also recognized his son’s agency—his ability to act independently and make his own choices freely—as well as his own agency as they learned to move together in the world.

In creating the game of pillow pop, parent and child found their own dance. Each moved with their own tune in time and space, and their tunes came together in harmony. When joy guides our choices, each person can be themselves, be together with others, and make progress. We can recognize that individuals have different reinforcers in a joint activity and that there is the potential to also develop and share reinforcers in these joint activities. And with strengthening bonds, this might simply come to mean enjoying being in each other’s company.

In another composite example, we consider a mother gently approaching her toddler with a sock puppet. The little boy is sitting on his knees on top of a bed, looking out the window, and flicking his fingers in his peripheral vision. The mother is oblivious to all of that, the boy is two years old and, although the movements are a little different, he’s doing what toddlers do. She begins to sing a children’s song that incorporates different animal sounds, sounds she discovered that her son loves to explore. After a moment, he joins her in making the animal sounds in the song. Then, he turns toward her and gently places his hands on her face. She’s singing for him. He reciprocates with his gaze and his caress, both actions full of appreciation and tenderness.

Family members might dream of the activities that they will enjoy together with their children as they learn and grow. Mothers and fathers and siblings may not have imagined singing sock puppets, playing pillow pop, or organizing kitchen swing games. But these examples here show the possibilities when we open up to one another and enjoy each other’s company. Our joy in our child and our family helps us rethink what is easy, what is hard, and what is progress.

All children can learn about the way into joyful relationships and, with grace, the dance continues as they grow up. This dance of human relationships is one that we all compose, first among members of our family, and then our schoolmates and, finally, out in the community. Shahla will always remember a film from the Anne Sullivan School in in Peru. The team knew they could help a young autistic boy at their school, but he would have to learn to ride the city bus across town by himself, including making several transfers along the way. The team worked out a training program for the boy to learn the way on the city buses, but the training program didn’t formally include anyone in the community at large. Still, the drivers and other passengers got to know the boy, this newest traveling member of their community, and they prompted him through the transfers from time to time. Through that shared dance, they amplified the community’s caring relationships.

When joy is present, we recognize the caring approach of others toward us and the need for kindness in our own approach toward others. We recognize the mutual assent within our togetherness, and the agency each of us enjoys in that togetherness. Joy isn’t a material good, but an energy found in curiosity, truth, affection, and insight. Once we recognize the radiating energy that joy brings, we will notice when it is missing and seek it out. Joy occupies those spaces where we are present and looking for the good. Like hope and love, joy is sacred.

When there is so much hate and so much resistance to truth and justice, joy is itself is an act of resistance. ― Nicolas O’Rourke

Overheard in the Wolfe House #327

Peggy (to Sam, after sharing news with cousins about second co-authored book on its way): You wrote a chapter for my first book, remember?

Sam (to cousins): Yeah, Mom can’t write a book by herself.