hope

Road trip

It took some time to notice, but both Sam and I agree the pandemic made our lives a little smaller.

Don’t get me wrong. There were things we did, things we neglected, routines we filled, habits we clung to, all that needed to change. And we stopped being busy for busy’s sake (what was that about?)

But ‘opting out’ also sets its own traps. A certain brittleness can settle in. We needed to stretch.

We’ve gone on cycling trips to help with that. Acadia National Park in 2021. Lake Champlain in 2022. But this year, we felt like we needed to nudge in another direction. After we were invited to a wedding in Phoenix, I got out the maps and started studying road trips. After all, Phoenix is just a few hours from California. As a good friend says, it’s just “map math.”

But I wasn’t planning a grand tour. This trip could reconnect us to our family’s origin story. Sam and his brother and sister were all born in Sacramento. Their father was principal tuba of the Sacramento Symphony until it went bankrupt. We lived there until Sam was 5 years old.

A road trip could help Sam see that he was a Californian and still belonged, if he wanted that option. We took the kids to California several times on summer trips. Sam went back to visit once on his own (his godparents live in Stockton) when he was in his 20s. But visiting a place for fun is different than visiting with an eye toward making a life there.

Many of us don’t always feel we have options and sometimes this seems more so for Sam. We planned this trip to explore his options,. The company he works for has a similar facility in Modesto. Touring the Modesto location could help him think about his future in new ways.

We had all the fun we could stay awake for in Phoenix, and headed out the next day. We took a nice, leisurely detour through Joshua Tree National Park (amazing!) and spent the night nearby.

Then the next day we headed to Modesto, stopping in Fresno. I suggested a stop at an underground garden. I thought it would be a world’s-largest-ball-of-twine-roadside-attraction type of stop, but it turned out to be a national landmark and completely charming.

The next day, we toured the Modesto facility and wouldn’t you know, Sam already knew some of the people working there. They didn’t have any openings right then, but that’s not how Sam thinks things through anyways.

In the month since, though, I’ve heard him say many, many times, “I have options now, Mom.”

Never, ever underestimate the power of a road trip.

Fledging

Late last week, walking with Fang, we came upon a red-shouldered hawk that had just made a kill near Rayzor Ranch Park. She was standing in a field with the varmint in her talons. The varmint seemed a little too silky brown and big to be a rabbit. There are a few jackrabbits in what is left of the old Rayzor Ranch. Or it could’ve been a nutria from the nearby retention pond.

I have seen this a few times before, this waiting after a kill. Once, a hawk had landed on a rat running in our postage stamp of a backyard in California. We watched through the dining room window as the hawk waited patiently until it was safe to fly off with her prey.

But this time, a scissor tail from the park decided there was no room in the new ‘hood for a hawk. I watched in wonder as the scissor tail dove for the hawk’s back, triggering the raptor to drop its prey and lift off. The scissor tail rode on that hawk’s back for a few hundred yards before veering off and back to the park.

I knew why she was doing that. A few days before, we were walking to that park (Fang likes Rayzor Ranch Park a lot.) At one point, I was almost face to face with a pair of scissor tails fledging their young — three little guys who didn’t have their scissor feathers yet, but were flying pretty well. They had just regrouped in one of the younger trees in the park, so they were barely hidden. The parents had tucked wings and tail feathers around them, as they all wiggled and peeped and got ready to fly again. We caught up with them a second time not far away, all three fledglings perched on a fence, side by side, peeping and wiggling and trying to decide whether Fang and I warranted another flight attempt as their parents flew overhead.

The sight of it all triggered a fast rewind in my brain, other times we’ve stumbled on fledging as we’ve walked. Once in a neighborhood to the east, a fledgling raptor had to be nearby–although I never saw it–because a Mississippi kite grazed me three times until we finally went around a corner. (I was so glad to be wearing a sturdy hat.)

Another time, I saw a pair of mourning doves standing unusually close to one another, perched on the next-door neighbor’s roof. I looked around and saw the fledgling in the gutter. The little guy wasn’t going to make it. I scooped up its body the next day.

Another time I didn’t see the fledgling until just after Fang spotted it hopping in the leaf litter beneath the oaks in McKenna Park. First the momma robin dove at Fang, and then the poppa. Fang immediately lost interest in the fledgling and was already crying uncle. But a call went out anyways and within seconds, every robin in the park was diving at the two of us, like a Hitchcock horror movie.

I got curious about how much scientists know about fledging and bird behavior. We don’t know a whole lot. I found a research study from 2018. This study suggested to researchers that fledging is negotiated between the young and the parents, with different species tolerating longer stays than others. Young birds that leave before they can fly very well have a higher mortality rate, of course. The scissor tails certainly had to fledge before their tails got too long, as my own mother adeptly noted. But the young that stay too long risk discovery by predators who bring jeopardy to the entire nest, parents included.

I’m not sure how well we humans do at fledging. Actually, in terms of survival of the human race, rather poorly, I think. We understand child development a little better than adult development. New research suggests a stage of emerging adulthood that warrants our closer attention. And, as most of us disability parents will tell you, fledging a child with a disability is tough. We have organized our culture in ways that discourage cooperation and care for one another, unless doing it for money. Can you imagine being like a robin and joining the entire flock to defend someone else’s child? We are too fond of gaming the economic rules so that one group or another gains an edge, instead of raising all boats. We do this change-up so often that it’s hard even for kids without disabilities to launch.

Maybe there’s a reason we know we are doomed. Maybe there are lessons from nature. Before it’s too late.

Keep learning

It’s New Year’s resolution time!

For the past five years, I’ve tried to make resolutions that are more meaningful. Whether it was saying “no” to buying things or “yes” to new challenges, or remembering that a solution already exists, those kind of resolutions brought more options and opportunities with them.

This year, for some reason, I had a hard time finding a new and meaningful pledge. To help, I read one story that suggested using a motivational word, like “breathe” or “focus” or “gratitude.” I liked the spirit of that suggestion, but wondered if a single word mantra could fall short of being meaningful.

Then, a couple things happened.

First, lightning struck a tree out front.

We were home when it happened, but we were in the back. We thought the lightning had struck a nearby transformer. We didn’t see the ball of fire that our neighbor did.

Still, we’d noticed that we’d lost our internet connection and the stereo was off. After our neighbor knocked on the front door, we saw the tree. At that point, we realized that we had a rolling disaster on our hands.

Sam spent hours troubleshooting. We brainstormed until we isolated all the things we had to fix, developed a working theory of what happened so we knew what else might be at risk, and decided what electric items were probably ok.

Based on the damage to the internet routers, we were a little scared until we could rule out a slow burn in the attic. We were grateful that–thanks to last year’s resolution to be prepared and resilient–most electrics had surge protection and had survived the strike, as did the surge protectors themselves.

Second, we took Sam’s Chevy Bolt on a long trip for the first time last weekend, from Denton to Austin and back. This was the first time to feel what EV owners call “range anxiety.” We discovered that the car’s information system was perfectly capable of predicting how many miles were left on the batteries. But we did worry whether the charging stations, which are few and far between, would be available and operational.

The trip went fine. The charging cost less than $8 on the way down, and was free on the way back. We had lunch during one charge and the fellow at the deli counter had SO many questions. Clearly, he was wondering whether driving an EV was an option for him. We answered all that we could but we were still learning, too, to which the deli guy summed, with so much wisdom, “It’s new.”

That’s was kind of an “aha” moment. We can’t always choose the moments that the world wants to teach something, and it does little good to close the door to those learning opportunities. I get grumpy solving problems that I’ve solved before; life is hard enough as it is. I don’t want to think about how appliances work. Yet, there was real power in learning how everything in our house worked. Driving to Austin is hard. Why make it harder by driving an EV? Yet, the car was quiet and a dream to drive. The charging breaks made the trip longer, but far less exhausting.

Hey, 2023. We will keep learning wherever the opportunity knocks.

Reciprocity

Hello, dear internet people! Are you ready for another excerpt from the new book? In Part Two: The Power of Connecting in Between Now and Dreams (pre-order here!), Shahla and I describe what it means for parents to connect to others as they nurture their children. When we connect to one another, we foster our shared growth and we strengthen the beautiful ways we can respond to our child. All kinds of people bring energy and wisdom to this journey — friends, family members, neighbors, professionals.

We were particularly inspired by the woman who cut Sam’s hair when he was in elementary and middle school. Connie taught us all a great lesson about reciprocity in relationships.

Edited excerpt below:

Reciprocity, the ways in which we demonstrate our care for one another and influence and depend on one another, breathes life and depth into our relationships. Mutual dependence is part of the human experience. The most meaningful relationships might start by attending the same class, then remembering birthdays or taking turns buying lunch, eventually deepening over the years by sharing child care or stepping in when someone starts cancer treatment. Reciprocal interactions with family and friends not only nourish our lives but can also help our autistic child by creating healthy and natural dependencies that bring progress in a sustainable way. When we understand and value reciprocity, we can boost its practice and our family’s quality of life.

Consider how young children learn to play together, for example. A child without autism approaches another child at preschool who is playing with cars, but just by watching the action at first. Then, the child picks up another car and begins playing along. After a minute or so, the two children create together an imaginary scenario for the cars. The play then becomes a learning, rewarding experience for both of them. That is one key of reciprocity—it is founded on mutual reinforcement. Each person receives some benefit in the relationship. The benefit may be transactional, meaning that something immediate happens that both parties value. The benefit can also be relational, meaning that things happen over time that are important to both individuals, and the value occurs when they are together. Reciprocity also involves coordinated and shared attention. Each person finds happiness in the other person’s happiness.

Many of us, including our children with autism, struggle with reciprocity, especially in the beginning. We are all in the process of learning about reciprocity in our own growth and development. Consider the circles of people around us who make our life better and help further our understanding. For most of us, family and close friends make up the inner circle. Groups of friends from spiritual communities, social clubs, or sporting activities are in the middle. The outer circle is filled with our acquaintances and professionals, such as our barber, school counselor, or family doctor.

Michael Ball, an elementary school guidance counselor in Texas, thought a lot about the friendship circles among the schoolchildren. The students with disabilities, he knew, would have a hard time developing friends for their inner circle from that middle circle of friendships. To change that environment, he created many circles of friends, inviting a student with a disability into his classroom once a week along with several children without a disability to spend time together. He offered the circle of friends an activity they would all enjoy. He was careful to pick something the child with a disability could do with some success, yet something all the children would enjoy doing or playing. Then, he’d let things unfold, working with them to solve problems along the way, if needed.

Children with autism often need coaching or other guided practice to take part in basic reciprocal social interactions, such as playing with siblings at home, with friends on the playground, or at a birthday party. Other children with autism may only need priming or a special script that details what happens and how best to respond to basic social cues. Some children may also need to expand their interests so they have more to share and can find common ground with family and friends.

We can be on the lookout for interactions, large and small, that take advantage of the power of reciprocity to build our child’s world. Our child’s ability to move through these moments brings its own kind of mastery. That’s one reason that therapists work hard to teach very young children with autism how to imitate other people. Once our child can imitate others in different ways and situations, they are better equipped to learn many more things and faster. Their ability to learn and master new things can become so powerful that some structured teaching becomes obsolete for them, and reciprocity fills the gap. Reciprocity gives us access to new relationships. It’s like the difference for all of us after we learned to read—then we read to learn. We enjoy reading, too. We access new worlds when we read.

These big moments don’t stop in childhood. In their paper on behavioral cusps and person-centered interventions, Garnett Smith and colleagues described Sarah, who was twenty-two. Sarah’s grandparents were concerned that she was a homebody. She enjoyed watching college basketball on television. Her grandparents took a chance and encouraged a friend to take Sarah to a game. She enjoyed herself so much that she continued attending games and other large events. Her reciprocal interactions with other people increased exponentially. She talked with workers at the concession stand and with the players after the game. She participated in halftime activities. Her world expanded. In fact, Sarah developed a whole new set of social skills around the experience, a classic example of a behavioral cusp. She was much less of a homebody. She even asked her grandparents to go to other sporting events.

We can be on the lookout, then, for activities that capture reciprocal contingencies. Our child can join other family members preparing the table for a meal. They can take turns playing a board game with a sibling. They can write thank-you notes. In this way, everyone can be our child’s ally. Life is filled with many gentle back-and-forth interactions, all worth fostering because they make life better and have the potential to create their own sustaining energy for our child’s progress.

For example, Peggy’s son, Sam, couldn’t tolerate haircuts when he was a toddler. Peggy resorted to cutting his hair while he slept. It worked well enough, but when her next-door neighbor, Judy, a stylist, heard how they were coping, she offered to help. Judy brought her supplies to the house. Sam sat in the high chair in front of a full-length mirror in the living room. Sam told Judy how to hold his hair as she cut it. She was patient and went along with his directions, and still managed to cut it well.

When the family moved, Peggy wondered whether she would have to find someone willing to make house calls, like Judy did. She found another stylist. Connie had a big heart and boundless sense of humor. She kept Sam looking good from boyhood trims through the high school trends.

The whole family got their haircuts on the same day. Connie would ask Sam’s advice, who was next in the chair, and everyone conferred on the plans. As he got older, Sam stopped telling Connie how to hold his hair and let her cut it as she would for any client. Then, the conversation became whatever Sam or Connie wanted to talk about. Getting haircuts became a powerful lesson in reciprocity. Judy opened the door, and Connie showed how reciprocity builds those connections. She understood that the circle of what is given and received grows wider with the years.

Then Connie got cancer. Sam understood that she became too weak to stand all day and cut people’s hair. He found another barber. The relationships, begun by the simple act of cutting Sam’s hair, had brought out the best in everyone. When Connie died a year later, Sam and the rest of the family felt the loss of a friend. They still miss her.

Joy

Joy gives us wings! ― Abdul-Baha

Review copies of the new book I co-wrote with Shahla arrived on Saturday. It’s such a pretty little thing. All that warmth and wisdom on the cover is on the inside, too. And so is some really smart science. The release date is April 2. You can pre-order here.

A while back, the publisher shared an excerpt on their blog. I’ve included it below, editor’s note and all. It’s from Part Three: The Power of Loving. And it’s called Joy.

Editor’s note: Autism Awareness month is becoming a call to action from the autism and neurodivergent communities for change from the rest of society. In this edited excerpt from their upcoming book with Different Roads, co-authors Shahla Ala’i-Rosales and Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe offer a specific call to action to both parents and professionals—to seek and maintain joy’s radiating energy in our relationships with our children.

Parents have the responsibility of raising their children with autism the best they can. This journey is part of how we all develop as humans—nurturing children in ways that honor their humanity and invite full, rich lives. Ala’i-Rosales and Heinkel-Wolfe’s upcoming book offers a roadmap for a joyful and sustainable parenting journey. The heart of this journey relies on learning, connecting, and loving. Each power informs the other and each amplifies the other. And each power is essential for meaningful and courageous parenting.

Ala’i-Rosales is a researcher, clinician, and associate professor of applied behavior analysis at the University of North Texas. Heinkel-Wolfe is a journalist and parent of an adult son with autism.

“Up, up and awaaay!” all three family members said at once, laughing. A young boy’s mother bent over and pulled her toddler close to her feet, tucking her hands under his arms and around his torso. She looked up toward her husband and the camera, broke into a grin, and turned back to look at her son. “Ready?” she said, smiling eagerly. The boy looked up at her, saying “Up . . .” Then he, too, looked up at the camera toward his father before looking back up at his mother to say his version of “away.” She squealed with satisfaction at his words and his gaze, swinging him back and forth under the protection of her long legs and out into the space of the family kitchen. The little boy had the lopsided grin kids often get when they are proud of something they did and know everyone else is, too. The father cheered from behind the camera. As his mother set him back on the floor to start another round, the little boy clapped his hands. This was a fun game.

One might think that the important thing about this moment was the boy’s talking (it was), or him engaging in shared attention with both his mom and dad (it was), or his mom learning when to help him with prompts and how to fade and let him fly on his own (it was), or his parents learning how to break up activities so they will be reinforcing and encourage happy progress (it was) or his parents taking video clips so that they could analyze them to see how they could do things better (it was) or that his family was in such a sweet and collaborative relationship with his intervention team that they wanted to share their progress (it was). Each one of those things is important and together, synergistically, they achieved the ultimate importance: they were happy together.

Shahla has seen many short, joyful home videos from the families she’s worked with over the years. On first viewing, these happy moments look almost magical. And they are, but that joyful magic comes with planning and purpose. Parents and professionals can learn how to approach relationships with their autistic child with intention. Children should, and can, make happy progress across all the places they live, learn, and play–home, school, and clinic. It is often helpful for families and professionals to make short videos of such moments and interactions across places. Back in the clinic or at home, they watch the clips together to talk about what the videos show and discuss what they mean and how the information can give direction. Joyful moments go by fast. Video clips can help us observe all the little things that are happening so we can find ways to expand the moments and the joy.

Let’s imagine another moment. A father and his preschooler are roughhousing on the floor with an oversized pillow. The father raises the pillow high above his head and says “Pop!” To the boy’s laughter and delight, his father drops the pillow on top of him and gently wiggles it as the little boy rolls from side to side. After a few rounds, father raises the pillow and looks at his son expectantly. The boy looks up at his father to say “Pop!” Down comes the wiggly pillow. They continue the game until the father gets a little winded. After all, it is a big pillow. He sits back on his knees for a moment, breathing heavily, but smiling and laughing. He asks his son if he is getting tired. But the boy rolls back over to look up at his dad again, still smiling and points to the pillow with eyebrows raised. Father recovers his energy as quickly as he can. The son has learned new sounds, and the father has learned a game that has motivated his child and how to time the learning. They are both having fun.

The father learned that this game not only encourages his child’s vocal speech but it was also one of the first times his child persisted to keep their interaction going. Their time together was becoming emotionally valuable. The father was learning how to arrange happy activities so that the two of them could move together in harmony. He learned the principles of responding to him with help from the team. He knew how to approach his son with kindness and how to encourage his son’s approach to him and how to keep that momentum going. He understood the importance of his son’s assent in whatever activity they did together. He also recognized his son’s agency—his ability to act independently and make his own choices freely—as well as his own agency as they learned to move together in the world.

In creating the game of pillow pop, parent and child found their own dance. Each moved with their own tune in time and space, and their tunes came together in harmony. When joy guides our choices, each person can be themselves, be together with others, and make progress. We can recognize that individuals have different reinforcers in a joint activity and that there is the potential to also develop and share reinforcers in these joint activities. And with strengthening bonds, this might simply come to mean enjoying being in each other’s company.

In another composite example, we consider a mother gently approaching her toddler with a sock puppet. The little boy is sitting on his knees on top of a bed, looking out the window, and flicking his fingers in his peripheral vision. The mother is oblivious to all of that, the boy is two years old and, although the movements are a little different, he’s doing what toddlers do. She begins to sing a children’s song that incorporates different animal sounds, sounds she discovered that her son loves to explore. After a moment, he joins her in making the animal sounds in the song. Then, he turns toward her and gently places his hands on her face. She’s singing for him. He reciprocates with his gaze and his caress, both actions full of appreciation and tenderness.

Family members might dream of the activities that they will enjoy together with their children as they learn and grow. Mothers and fathers and siblings may not have imagined singing sock puppets, playing pillow pop, or organizing kitchen swing games. But these examples here show the possibilities when we open up to one another and enjoy each other’s company. Our joy in our child and our family helps us rethink what is easy, what is hard, and what is progress.

All children can learn about the way into joyful relationships and, with grace, the dance continues as they grow up. This dance of human relationships is one that we all compose, first among members of our family, and then our schoolmates and, finally, out in the community. Shahla will always remember a film from the Anne Sullivan School in in Peru. The team knew they could help a young autistic boy at their school, but he would have to learn to ride the city bus across town by himself, including making several transfers along the way. The team worked out a training program for the boy to learn the way on the city buses, but the training program didn’t formally include anyone in the community at large. Still, the drivers and other passengers got to know the boy, this newest traveling member of their community, and they prompted him through the transfers from time to time. Through that shared dance, they amplified the community’s caring relationships.

When joy is present, we recognize the caring approach of others toward us and the need for kindness in our own approach toward others. We recognize the mutual assent within our togetherness, and the agency each of us enjoys in that togetherness. Joy isn’t a material good, but an energy found in curiosity, truth, affection, and insight. Once we recognize the radiating energy that joy brings, we will notice when it is missing and seek it out. Joy occupies those spaces where we are present and looking for the good. Like hope and love, joy is sacred.

When there is so much hate and so much resistance to truth and justice, joy is itself is an act of resistance. ― Nicolas O’Rourke

Refrigerator Mother 2.0

Only a few generations ago, some doctors blamed mothers for their children’s autism. Psychologists wrote long theoretical papers based on their observations of mothers and their children. They concluded that autism mothers were cold and that their lack of love triggered the child’s autism.

If you stop to think about that idea for a minute, those explanations were quite a leap. And a cruel one at that.

We humans look for patterns in the world around us–it’s almost one of our super-powers. We use the information to make meaning, and create loops of ferocious thinking that make the world around us a little better.

Therefore, knowing that we’re supposed to make things better, the Refrigerator Mother explanation for autism just begs the question. How much did those early theoreticians consider and—most importantly, rule out—before concluding they’d observed a pattern of mothers who don’t love their children?

Granted, many people were immediately skeptical of these mother-blaming theories, including other professionals and autism families. The theories fell after a generation, but the damage was done to the families forced to live under that cloud as they raised their children.

And, the blame game is still out there.

The latest iteration has started in a similar way, with people seeing problematic patterns in autism treatment. Young adults with autism are finding their way in the world. Some of them had good support growing up, but the world isn’t ready for them. Some of them had inadequate support growing up, so they have an added burden as they make their way in a world that isn’t ready for them either. Some are speaking up not just about the world’s unreadiness but also about that burden. We must listen. Autistic voices can help us find new patterns and new meaning and build a better world for all of us.

We should be careful about letting one person’s experience and voice serve as the representation for the whole, because that’s how the blame game begins. Even back in the old days, when information was scarce, we had the memoirs of Temple Grandin, Sean Barron, and Donna Williams to show us how different the experiences can be. As Dr. Stephen Shore once said, if you’ve met one person with autism, then you’ve met one person with autism.

Here’s an example of how that can break down: some now argue that asking an autistic child to make eye contact, as a part of treatment service, is inherently abusive because eye contact feels bad for them. Missing from that argument is the basic context, the understanding that for humans to survive, we need to connect to one another. For most of us, eye contact is the fundamental way we begin to connect, from the very first time we hold and look at our new baby and our baby looks back at us.

I asked Sam recently (and for the first time) whether making eye contact is hard or painful for him. I told him I was especially curious now that eye contact changed for all of us after living behind face masks for a year. He said this, “Eye contact is very powerful. I wonder whether I make other people uncomfortable with eye contact.”

He’s right. It is powerful. And he just illustrated the point about one person’s perspective.

When Sam was young, we never forced him to look at us. But after a speech therapist suggested using sign language to boost his early communication, I found the sign for “pay attention” often helped us connect.

The additional movement of hands to face usually sparked him to turn his head or approach me or Mark in some way, so we were fairly sure we had his attention and that was enough to proceed with whatever was next. Over the years, we’ve shared eye contact in lots of conversations and tasks. But if not, we recognized the other ways that we were connecting and I didn’t worry about it.

All of this context—both the need to survive and the difficulty with a basic skill needed for that survival—cannot go missing from any conversation about the value of teaching an autistic child. Some people with autism do learn how to make eye contact early on and are fine with it. Some don’t. For this example, then, we can listen carefully to adults with autism and their advocates as they flag patterns from their bad experiences with learning to make eye contact and make changes. But that fundamental need to connect and share attention remains.

That’s when we also need to remember our tendency to blame others when our troubles feel intractable. Sometimes, in these fresh arguments over how autism treatment should proceed, I hear that same, tired pattern of blame I’ve heard since Sam was born. Take it from a worn-out mother who’s been blamed plenty over the years: some arguments are just another round of the same, they just come inside an elaborate wrapper of mother’s-helper blaming instead.

All the families I know truly love their children and are learning how best to respond to them. We can’t forget that parents have a responsibility to raise their child as best they can. Let’s talk, please. But please also, let’s spare the rollout of Refrigerator Mother 2.0, because it could cost us a generation of progress.

Take it to all four corners

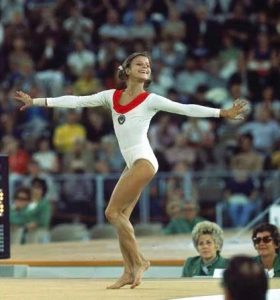

Olga Korbut changed the face of gymnastics when I was in junior high school. She looked so graceful and athletic in Seventeen magazine’s photos from her performance at the 1972 Olympics. As you might imagine, many of the wiggly tweens in my gym class were excited that our teacher added a gymnastics unit, largely because of what Korbut had inspired. Now, we could all experiment with moving through the world that way. That’s also when I learned one of the rules of floor exercise: a gymnastics routine can borrow from dance and mix in lots of tumbling, but it must also go to all four corners of the mat.

It’s a curious rule, yet wise when you think about it. It requires the competitor to be thorough as they challenge their body. I started thinking about that rule again recently and decided to add it to my ongoing pursuit of small, yet large, New Year’s resolutions. For 2021, I plan to take things to all four corners.

Last year’s resolution, Wear An Apron, feels prescient now, given the pandemic. We certainly spent a lot more time in the kitchen in 2020. But the bigger idea behind it–that whatever problem we faced, someone out there solved it already–kept us grounded, too. Online, we found Khan Academy to help Sam (and me) learn calculus as well as a sewing pattern and instructions for face masks vetted by some pragmatic nurses in Iowa. On YouTube, I started following a smart yoga instructor and my dad’s favorite backyard gardener, a fellow in England whose bona fides begin with his unapologetically dirty hands. Even streaming The Repair Shop revealed wide-ranging wisdom about problems I didn’t even know could be solved. Awesome.

Thinking ahead to this year, I remembered an editor who would remind us reporters to nail down all four corners of an investigative story before publication. Smart advice, but it also created a defensive image in my mind’s eye rather than something inspired by filling up the space of a gymnastics mat. Don’t get me wrong, it’s important to be able to rigorously defend your choices and actions, but the big idea for 2021 shouldn’t be about the pursuit of perfection. Instead, going to all four corners means planning thoroughly, and being careful and deliberate.

Raising kids, especially someone like Sam who needed so much, shunts the pursuit of perfection to the side in favor of steps that move toward progress. But I can’t say we always took it to all four corners.

For example, Sam does pretty well in the kitchen. All my children learned cooking and cleaning basics and food safety. Now, Sam does so well with some recipes that I can plan time off in the kitchen when he steps up. But I know we haven’t taken it to all four corners. Managing a kitchen is hard with all the planning and shopping. And the principles of cooking that let you tackle a new recipe, that’s something else, too.

So, not such a small idea after all. But it may be warranted for 2021, because I bet once we let loose the reins from the pandemic, there could be many things that need to be thought through again, and to all four corners.

The man, the mail-in ballot, and meaning

Sam signed up for mail-in ballots after the pandemic began. Texas allows individuals with disabilities and voters age 65 and older to vote by mail.

He registered as a Republican after learning that he would miss at least one upcoming local election if he didn’t. Turns out, he got two test runs with the mail-in-ballot routine before the big one — the November presidential — arrived. In mid-July, Denton County had a run-off between two GOP nominees for state judge in the 431st District Court. Then we unexpectedly had a crowded race of Republicans and a lone Democrat vying to succeed our former State Senator, who let no grass get under his ultra-ambitious feet as he hopscotched his way from newbie Texas resident and the state legislature into Congress this year.

When the November ballot arrived in the mail in early October, Sam opened up the envelope and spread its contents across the dining room table. He grabbed a pen and colored in the box to vote for president. He took a deep breath, saying that it felt powerful to vote for Joe Biden. He stood up and announced then that he would come back to finish the rest of the ballot later.

The ballot was long. It included federal, state, and county offices. It also included city offices, as the Texas governor postponed local races because of the pandemic. When Sam returned to finish voting, he surprised me how prepared he was to make informed choices all the way down.

He’d been watching our current president, and deteriorating conditions for a long time. He had thought long and hard about how to vote for change.

Our current president proved himself irredeemable to us when he mocked a reporter with a disability in 2015. The past four years have been so bad that it was genuinely shocking — and should not have been — to watch Joe Biden return the affection of a man with Down syndrome who rushed to hug him several years ago.

It’s a hard thing to explain to people who haven’t been on this journey, what it is like to regularly experience another human being’s black-heartedness in a deeply personal way. When Sam was little, we shielded him. Now that he’s an adult, we have to talk about it.

Those are the worst conversations. Not because Sam gets hurt, or because we don’t have strategies for him, but because we parents are hard-wired to protect our children. When I hear these stories, or watch things unfold in front of me, I want to slap somebody. I haven’t so far, so I guess the strategies are working for me, too.

Sam told me about a week before Election Day that he was going to want to watch the returns on election night, in hopes that his choice would prevail with everyone else. Election night was tough, but as the days went by, you could see the tension lift. Sam is not just relieved, but happy.

“I voted for Joe Biden as hard as I could,” he said.

Intention makes the little, big

One of Sam’s first speech therapists missed many scheduled home sessions. Early childhood programs usually begin in the home for toddlers who need services like Sam did. By the time I thought I should complain about her absences, however, Sam was “aging out” of the program. Once a child reaches 3 years old, education officials offer preschool along with speech and other services. Preschool offers a far richer environment to learn much more and much faster — as long as your child is ready to learn that way. Sam went to preschool where another speech therapist was assigned to work with him. She kept her schedule.

I’ve been thinking a lot about our family’s first autism experiences as Shahla and I put the finishing touches on our book. Given what could have been for our family 30 years ago, I feel really lucky.

It’s odd to call it lucky that Sam missed so many of his first speech therapy sessions. I didn’t consider it lucky back then. Sam had just been diagnosed. There was a lot of work to do. The therapist wasn’t doing her part of the work.

Yet, when she did keep her appointments, they were powerful. She took time to explain to me what she was doing as she worked with Sam. She wanted me to understand and keep things going when she wasn’t around. Since she missed so many of her appointments, I pivoted toward that goal pretty fast. (Honestly, I think she was battling depression.) I wasn’t a trained speech therapist. But I was soon thinking about Sam’s speech development all the time and responding to him in those thousand little moments you have every day with your child.

It took a while to see how lucky that was.

Sam was in primary school when I met Shahla. Shahla also helped with his progress, but that, too, took a while for me to see. There was still a lot of work to do and I was always trying to line up help. Shahla and I would chat occasionally about how things were going. I would share a story of some happening, often whatever was vexing us at the time and she would explain what was going on behind the curtain. Those little conversations were actually a deep dive for me. I understood better what was happening with Sam and where to go next — just as his wayward speech therapist was trying to show us.

We were learning to work smarter, not just harder, of course. But there was something else.

Sam couldn’t be forced or coerced — not that we wanted to work that way. Like many children with autism, in my opinion, the ways that he protected himself from the outside world were effective and strong. Still, we made progress. His best outcomes came after we approached things in a straightforward way with his full participation. The better we got at being deliberate, respectful, and intentional, the more momentum we created.

Even though Sam is a grown-ass man, we still seize the small moments to make a difference. I’ve been working at home for a while now, and that’s come with more opportunities for those small moments. With Mark gone and both Sam and I working full-time for the past decade, we didn’t have many. These days, we can chat over breakfast or lunch (or both) before Sam heads to work. Like every young adult, Sam sometimes turns his adult mind back to childhood experiences and tries to make sense of them. I’m glad to be here as he puzzles through all that. I’d like to think he’s puzzling through more because of these opportunities.

These days, he’s also been thinking a lot about why alarm bells bothered him so much when he was in elementary school. I told him he wasn’t alone, that no one likes that sound. That was a revelation to him, since apparently the rest of us hide that aversion so well. But he’s really wrestling with this, breaking things down into the science of sound, analyzing sound waves, and figuring how to manipulate them. He wants to make his own science to help others who hate alarm bells as much as he did. Who knows? Maybe he’s got something like Temple Grandin’s squeeze machine going in his sound lab back there, ready to banish those anxiety-making monsters once and for all.

Happy progress, indeed.

Community of practice

I finally moved my personal things out of my old office space, thanks to the help of a co-worker who also had to listen to me prattle on about things like how many piano makers there were before and after the Great Depression and why that might mean something to journalism now.

I have a century-old, upright grand piano. My parents got it for me when I was first learning to play. It has a big sound, especially after I had it rebuilt about ten years ago. The man who rebuilt it told me that before the Great Depression there were more than 400 piano makers in the United States. After the Great Depression, there were just two.

That seemed a stunning loss to me. Many people love music and enjoy playing, even if just for themselves. Pianos are among a handful of instruments that play both melody and harmony. However, our attention is never guaranteed, and our money usually follows wherever our attention goes.

That same drifting attention is happening to the news business now. Businesses needed your attention, so they got it by putting their advertisements next to news. Newspapers were among the original public-private partnerships. The better quality the news — a real public service at that point — the more valuable that space got. That is, until our attention started to drift.

One of the Denton newspaper’s most popular reports was the police blotter, at least before the pandemic began. It had long been a guilty pleasure for readers. Of course, now they can find even more guilty reading pleasures on Facebook, a company only too happy to hoover up the advertising revenue as people’s attention drifts over there. Probably in another year or two, there will be only a handful of news outlets left because the business model that extracted value out of our attention has changed so much.

Some people have finally figured that out, that the business model now is for people who recognize they need solid journalism to make sound business decisions and to make good public policy decisions.

Without that, we will soon have warlords squabbling for years while ticking time bombs sit in our harbors.

I’m ready to stop thinking about the business model and start thinking about the community of practice — journalists are a group of people concerned about the quality of information, how it’s gathered and vetted, and how to do it better, and the best way to do that is by debating all those values regularly among your peers — and then publishing or broadcasting.

This community of practice in journalism is also the same thing that people like to criticize as “the priesthood” or the “legacy elite” or “media bubble” or whatever other pejorative they want to hurl at the wall that might stick for the moment. But humans create communities of practice because they care about what they do and want to do it better, and scholars are beginning to recognize how much this phenomenon has helped all kinds of businesses do better and make progress in our modern world.

My first introduction to communities of practice came in the autism world, with parents sharing wisdom and such. Eventually, parents started seeing that the best therapists with the most powerful ideas kind of hung out together and fed off each other’s practice and research. No one was talking to you about a “community of practice,” but if you wanted the best for your child, you always wanted to be close to that, since chances were higher that your kid would benefit from all that supercharged brainpower and skill.

I encouraged Michael and Paige to find the equivalent as they ventured out into the working world, although I didn’t have the vocabulary for it at the time. At the University of Iowa, they organized the dorm into micro-communities that way and Paige fell right in. She’s still friends with many of her original writing community. Michael got a power introduction to the concept as a behavior tech in the autism world. He’s like a heat-seeking missile for that value where he works.

Journalists sometimes compete with each other, but we benefit from each other’s successes and critical takes on each other’s work. The successful business model(s) will depend on the rigor within our community of practice. As business models disappear and fail, that doesn’t mean the community of practice must also, but it makes it a lot harder. Until the emerging business models stabilize, our environment is ripe for propaganda disguised as news. But if our community of practice disappears, no business model will save it.

Just like the piano makers.