love

Dad

My dad died Sunday.

It was so hard to let him go. He had three wishes: to die at home, to have no service, and to leave his body to the medical school. Those are tough promises to keep, but we did it.

A good friend told me a few months back that it would probably fall to me to write the obituary and I knew she was right. I penciled out his biography. Once in a while, I’d ask him a question or I’d listen carefully as he told someone a story. Bits and pieces got folded into his biography until all that was needed was the top and bottom that make it into an obituary.

Except that, as I’ve learned through the years as a reporter, a person’s family might know them, but they may not know the C.V. After several rounds of family edits, this was the final cut:

Donald Eugene Heinkel, longtime Windsor resident and devoted family man, died September 10. He was 88.

He was born April 20, 1935, in Cedarburg, Wisconsin, to Gerald Heinkel and Leocadia (nee Schesta) Heinkel, the second of five children. Although the family eventually settled in Rockford, Illinois, a large polio outbreak that began in 1937 in Chicago and northern Illinois sent him, along with his mother and siblings, to live near family in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, a tiny town on the western shores of Lake Michigan.

After he graduated high school and completed one year of college, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He was stationed in Japan following the Korean War. When it was time to return stateside, he asked his commanding officer to sail home, since he had been on shore duty in Japan. He boarded the USS Yorktown and finished his tour of duty on the USS Midway where he worked filing weather reports.

He took advantage of the G.I. Bill to enroll at Marquette University. He met his wife, Carol, while driving for a laundry service where she also worked. They married November 7, 1959. He earned both a bachelor’s and master’s of science degrees in biology at Marquette.

He then worked for two years as research technician. After realizing he’d be working from grant to grant, he went back to Marquette to enroll in dental school. In his final year of studies, he saw a notecard on a bulletin board. A small farming town in central Wisconsin needed a dentist. In 1970, the family moved to New London and he opened his practice on the second floor of a medical building. The practice grew and he moved to a spacious office building on the banks of the Embarrass River.

The central Wisconsin winters eventually proved too harsh. In 1978, he brought his family to Windsor, Colorado, where he bought an historic building on Fifth Street and did much of the rehabilitation work himself before opening a new practice to serve the fast-growing community.

A skillful woodworker, his first project—a lamp base that he couldn’t quite make square in 7th grade shop class—belied the artist within. As an adult, he took woodworking classes. In the first class, he built a twin bed that nearly every family member has slept in at some point, until he finally kept the bed for himself. His skill and creativity blossomed as he built furniture and decorative items from both classic patterns and his own designs, including tiny end tables assembled from scraps of Texas mesquite.

The move to Colorado also gave him a chance to join with other actors to form the Windsor Community Playhouse. He enjoyed playing a wide range of characters, from the terrifying and murderous Waldo Lydecker in Laura to the hilarious, hapless Father Virgil in Nunsense.

He sold the dental practice to Patrick Weakland and went to Saudi Arabia to practice for several years so that he and Carol could travel and then retire.

He taught himself to play guitar, and was an enthusiastic and accomplished golfer. He hit three holes-in-one during his amateur career, including sinking the same hole twice at Highland Hills and another during tournament play at Pelican Lakes. He also traveled to Scotland to play a round at St. Andrews, the home of golf, and to Augusta, Georgia, to volunteer at the Masters Tournament.

He was preceded in death by his parents; his brothers, Richard Heinkel and Dennis Heinkel; one nephew and one son-in-law. He is survived by his wife of 63 years, Carol; four daughters, Peggy, Chris, Karen and Teresa; three sons-in-law; five grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; four step-grandchildren and their six children; his sisters, Mary Ann Scott, of Arizona, and Helena Wagner, of Hawaii; and sixteen nieces and nephews, more or less.

The family is deeply grateful for the help of Dr. Douglas Kemme, Dr. Daniel Pollyea at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz Medical Campus, the Colorado State Anatomical Board, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the caring staff of Pathways of Northern Colorado and Homewatch Caregivers.

Adamson Life Celebration Home is in charge of arrangements. No service is planned. Donations may be made to the above organizations or to the charity of your choice. Or, in lieu of donations, make a toast to Don at the 19th hole.

Some bits and pieces from his biography ended up on the cutting room floor.

For example, the family didn’t want to emphasize his military service, because he saw that as a duty. No fanfare required.

In working other obituaries for the newspaper, I’ve sensed that when an individual leaves home–whether they enlisted, or entered college, or started their first full-time job–you often get a glimpse into their origin story.

At one point, my cousin got Dad talking about basic training in the Navy. Dad’s assigned spot for morning calisthenics landed him right in front of the drill sargeant. After the first day, he knew no good would come of it. Meanwhile, he was also offered a menial assignment. There were several bulletin boards around the base where posters and announcements needed to be swapped out and updated daily. Dad accepted the job. He said he knew it was a 20-minute chore, but he always made sure it lasted an hour or two, to spare him the morning calisthenics.

He told us more than once that he and a buddy went to the top of Mount Fuji. Finally, I got him to share details. They rode the train up. It was spectacular. When it was time to go home, they got on the wrong train down. The east side train had wayfinding signs in Japanese and English, to help the tourists. The west side did not. He and his buddy knew they were cutting it close. But they figured their way out and got back to base before they were awol.

I love those stories. They say so much about my dad. He was in the first year of a seminary college when he dropped out to enlist. What an incredible pivot, especially when you consider that the Korean War had just ended.

His life is full of these leap-and-the-net-will-appear moments. Growing up, I didn’t see him that way. But that’s the limit of your kid vision. Your dad is just always just there, punching the clock, supporting the family. Thank goodness we had the gift of time so all that richness could come through.

Being there, being present has incredible value, too. After Mark died, Dad was a touchstone for my kids. Sam adored his grandpa, and their weekly zoom chats. Family has helped him, and so have friends these past few days. His Born 2 Be friends at the riding stables have surrounded him. I’m grateful for our little village here. If you are so inclined, please consider Born 2 Be, and in my dad’s memory, during North Texas Giving Day.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #329

Sam (getting in the car): Get in the back, Fang.

Peggy: He’s gotta give you a kiss first.

Sam: That’s the thing with love. Sometimes you can’t escape it.

Reciprocity

Hello, dear internet people! Are you ready for another excerpt from the new book? In Part Two: The Power of Connecting in Between Now and Dreams (pre-order here!), Shahla and I describe what it means for parents to connect to others as they nurture their children. When we connect to one another, we foster our shared growth and we strengthen the beautiful ways we can respond to our child. All kinds of people bring energy and wisdom to this journey — friends, family members, neighbors, professionals.

We were particularly inspired by the woman who cut Sam’s hair when he was in elementary and middle school. Connie taught us all a great lesson about reciprocity in relationships.

Edited excerpt below:

Reciprocity, the ways in which we demonstrate our care for one another and influence and depend on one another, breathes life and depth into our relationships. Mutual dependence is part of the human experience. The most meaningful relationships might start by attending the same class, then remembering birthdays or taking turns buying lunch, eventually deepening over the years by sharing child care or stepping in when someone starts cancer treatment. Reciprocal interactions with family and friends not only nourish our lives but can also help our autistic child by creating healthy and natural dependencies that bring progress in a sustainable way. When we understand and value reciprocity, we can boost its practice and our family’s quality of life.

Consider how young children learn to play together, for example. A child without autism approaches another child at preschool who is playing with cars, but just by watching the action at first. Then, the child picks up another car and begins playing along. After a minute or so, the two children create together an imaginary scenario for the cars. The play then becomes a learning, rewarding experience for both of them. That is one key of reciprocity—it is founded on mutual reinforcement. Each person receives some benefit in the relationship. The benefit may be transactional, meaning that something immediate happens that both parties value. The benefit can also be relational, meaning that things happen over time that are important to both individuals, and the value occurs when they are together. Reciprocity also involves coordinated and shared attention. Each person finds happiness in the other person’s happiness.

Many of us, including our children with autism, struggle with reciprocity, especially in the beginning. We are all in the process of learning about reciprocity in our own growth and development. Consider the circles of people around us who make our life better and help further our understanding. For most of us, family and close friends make up the inner circle. Groups of friends from spiritual communities, social clubs, or sporting activities are in the middle. The outer circle is filled with our acquaintances and professionals, such as our barber, school counselor, or family doctor.

Michael Ball, an elementary school guidance counselor in Texas, thought a lot about the friendship circles among the schoolchildren. The students with disabilities, he knew, would have a hard time developing friends for their inner circle from that middle circle of friendships. To change that environment, he created many circles of friends, inviting a student with a disability into his classroom once a week along with several children without a disability to spend time together. He offered the circle of friends an activity they would all enjoy. He was careful to pick something the child with a disability could do with some success, yet something all the children would enjoy doing or playing. Then, he’d let things unfold, working with them to solve problems along the way, if needed.

Children with autism often need coaching or other guided practice to take part in basic reciprocal social interactions, such as playing with siblings at home, with friends on the playground, or at a birthday party. Other children with autism may only need priming or a special script that details what happens and how best to respond to basic social cues. Some children may also need to expand their interests so they have more to share and can find common ground with family and friends.

We can be on the lookout for interactions, large and small, that take advantage of the power of reciprocity to build our child’s world. Our child’s ability to move through these moments brings its own kind of mastery. That’s one reason that therapists work hard to teach very young children with autism how to imitate other people. Once our child can imitate others in different ways and situations, they are better equipped to learn many more things and faster. Their ability to learn and master new things can become so powerful that some structured teaching becomes obsolete for them, and reciprocity fills the gap. Reciprocity gives us access to new relationships. It’s like the difference for all of us after we learned to read—then we read to learn. We enjoy reading, too. We access new worlds when we read.

These big moments don’t stop in childhood. In their paper on behavioral cusps and person-centered interventions, Garnett Smith and colleagues described Sarah, who was twenty-two. Sarah’s grandparents were concerned that she was a homebody. She enjoyed watching college basketball on television. Her grandparents took a chance and encouraged a friend to take Sarah to a game. She enjoyed herself so much that she continued attending games and other large events. Her reciprocal interactions with other people increased exponentially. She talked with workers at the concession stand and with the players after the game. She participated in halftime activities. Her world expanded. In fact, Sarah developed a whole new set of social skills around the experience, a classic example of a behavioral cusp. She was much less of a homebody. She even asked her grandparents to go to other sporting events.

We can be on the lookout, then, for activities that capture reciprocal contingencies. Our child can join other family members preparing the table for a meal. They can take turns playing a board game with a sibling. They can write thank-you notes. In this way, everyone can be our child’s ally. Life is filled with many gentle back-and-forth interactions, all worth fostering because they make life better and have the potential to create their own sustaining energy for our child’s progress.

For example, Peggy’s son, Sam, couldn’t tolerate haircuts when he was a toddler. Peggy resorted to cutting his hair while he slept. It worked well enough, but when her next-door neighbor, Judy, a stylist, heard how they were coping, she offered to help. Judy brought her supplies to the house. Sam sat in the high chair in front of a full-length mirror in the living room. Sam told Judy how to hold his hair as she cut it. She was patient and went along with his directions, and still managed to cut it well.

When the family moved, Peggy wondered whether she would have to find someone willing to make house calls, like Judy did. She found another stylist. Connie had a big heart and boundless sense of humor. She kept Sam looking good from boyhood trims through the high school trends.

The whole family got their haircuts on the same day. Connie would ask Sam’s advice, who was next in the chair, and everyone conferred on the plans. As he got older, Sam stopped telling Connie how to hold his hair and let her cut it as she would for any client. Then, the conversation became whatever Sam or Connie wanted to talk about. Getting haircuts became a powerful lesson in reciprocity. Judy opened the door, and Connie showed how reciprocity builds those connections. She understood that the circle of what is given and received grows wider with the years.

Then Connie got cancer. Sam understood that she became too weak to stand all day and cut people’s hair. He found another barber. The relationships, begun by the simple act of cutting Sam’s hair, had brought out the best in everyone. When Connie died a year later, Sam and the rest of the family felt the loss of a friend. They still miss her.

Joy

Joy gives us wings! ― Abdul-Baha

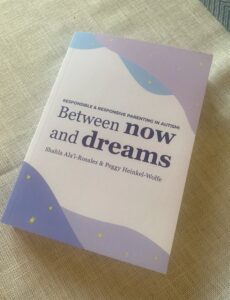

Review copies of the new book I co-wrote with Shahla arrived on Saturday. It’s such a pretty little thing. All that warmth and wisdom on the cover is on the inside, too. And so is some really smart science. The release date is April 2. You can pre-order here.

A while back, the publisher shared an excerpt on their blog. I’ve included it below, editor’s note and all. It’s from Part Three: The Power of Loving. And it’s called Joy.

Editor’s note: Autism Awareness month is becoming a call to action from the autism and neurodivergent communities for change from the rest of society. In this edited excerpt from their upcoming book with Different Roads, co-authors Shahla Ala’i-Rosales and Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe offer a specific call to action to both parents and professionals—to seek and maintain joy’s radiating energy in our relationships with our children.

Parents have the responsibility of raising their children with autism the best they can. This journey is part of how we all develop as humans—nurturing children in ways that honor their humanity and invite full, rich lives. Ala’i-Rosales and Heinkel-Wolfe’s upcoming book offers a roadmap for a joyful and sustainable parenting journey. The heart of this journey relies on learning, connecting, and loving. Each power informs the other and each amplifies the other. And each power is essential for meaningful and courageous parenting.

Ala’i-Rosales is a researcher, clinician, and associate professor of applied behavior analysis at the University of North Texas. Heinkel-Wolfe is a journalist and parent of an adult son with autism.

“Up, up and awaaay!” all three family members said at once, laughing. A young boy’s mother bent over and pulled her toddler close to her feet, tucking her hands under his arms and around his torso. She looked up toward her husband and the camera, broke into a grin, and turned back to look at her son. “Ready?” she said, smiling eagerly. The boy looked up at her, saying “Up . . .” Then he, too, looked up at the camera toward his father before looking back up at his mother to say his version of “away.” She squealed with satisfaction at his words and his gaze, swinging him back and forth under the protection of her long legs and out into the space of the family kitchen. The little boy had the lopsided grin kids often get when they are proud of something they did and know everyone else is, too. The father cheered from behind the camera. As his mother set him back on the floor to start another round, the little boy clapped his hands. This was a fun game.

One might think that the important thing about this moment was the boy’s talking (it was), or him engaging in shared attention with both his mom and dad (it was), or his mom learning when to help him with prompts and how to fade and let him fly on his own (it was), or his parents learning how to break up activities so they will be reinforcing and encourage happy progress (it was) or his parents taking video clips so that they could analyze them to see how they could do things better (it was) or that his family was in such a sweet and collaborative relationship with his intervention team that they wanted to share their progress (it was). Each one of those things is important and together, synergistically, they achieved the ultimate importance: they were happy together.

Shahla has seen many short, joyful home videos from the families she’s worked with over the years. On first viewing, these happy moments look almost magical. And they are, but that joyful magic comes with planning and purpose. Parents and professionals can learn how to approach relationships with their autistic child with intention. Children should, and can, make happy progress across all the places they live, learn, and play–home, school, and clinic. It is often helpful for families and professionals to make short videos of such moments and interactions across places. Back in the clinic or at home, they watch the clips together to talk about what the videos show and discuss what they mean and how the information can give direction. Joyful moments go by fast. Video clips can help us observe all the little things that are happening so we can find ways to expand the moments and the joy.

Let’s imagine another moment. A father and his preschooler are roughhousing on the floor with an oversized pillow. The father raises the pillow high above his head and says “Pop!” To the boy’s laughter and delight, his father drops the pillow on top of him and gently wiggles it as the little boy rolls from side to side. After a few rounds, father raises the pillow and looks at his son expectantly. The boy looks up at his father to say “Pop!” Down comes the wiggly pillow. They continue the game until the father gets a little winded. After all, it is a big pillow. He sits back on his knees for a moment, breathing heavily, but smiling and laughing. He asks his son if he is getting tired. But the boy rolls back over to look up at his dad again, still smiling and points to the pillow with eyebrows raised. Father recovers his energy as quickly as he can. The son has learned new sounds, and the father has learned a game that has motivated his child and how to time the learning. They are both having fun.

The father learned that this game not only encourages his child’s vocal speech but it was also one of the first times his child persisted to keep their interaction going. Their time together was becoming emotionally valuable. The father was learning how to arrange happy activities so that the two of them could move together in harmony. He learned the principles of responding to him with help from the team. He knew how to approach his son with kindness and how to encourage his son’s approach to him and how to keep that momentum going. He understood the importance of his son’s assent in whatever activity they did together. He also recognized his son’s agency—his ability to act independently and make his own choices freely—as well as his own agency as they learned to move together in the world.

In creating the game of pillow pop, parent and child found their own dance. Each moved with their own tune in time and space, and their tunes came together in harmony. When joy guides our choices, each person can be themselves, be together with others, and make progress. We can recognize that individuals have different reinforcers in a joint activity and that there is the potential to also develop and share reinforcers in these joint activities. And with strengthening bonds, this might simply come to mean enjoying being in each other’s company.

In another composite example, we consider a mother gently approaching her toddler with a sock puppet. The little boy is sitting on his knees on top of a bed, looking out the window, and flicking his fingers in his peripheral vision. The mother is oblivious to all of that, the boy is two years old and, although the movements are a little different, he’s doing what toddlers do. She begins to sing a children’s song that incorporates different animal sounds, sounds she discovered that her son loves to explore. After a moment, he joins her in making the animal sounds in the song. Then, he turns toward her and gently places his hands on her face. She’s singing for him. He reciprocates with his gaze and his caress, both actions full of appreciation and tenderness.

Family members might dream of the activities that they will enjoy together with their children as they learn and grow. Mothers and fathers and siblings may not have imagined singing sock puppets, playing pillow pop, or organizing kitchen swing games. But these examples here show the possibilities when we open up to one another and enjoy each other’s company. Our joy in our child and our family helps us rethink what is easy, what is hard, and what is progress.

All children can learn about the way into joyful relationships and, with grace, the dance continues as they grow up. This dance of human relationships is one that we all compose, first among members of our family, and then our schoolmates and, finally, out in the community. Shahla will always remember a film from the Anne Sullivan School in in Peru. The team knew they could help a young autistic boy at their school, but he would have to learn to ride the city bus across town by himself, including making several transfers along the way. The team worked out a training program for the boy to learn the way on the city buses, but the training program didn’t formally include anyone in the community at large. Still, the drivers and other passengers got to know the boy, this newest traveling member of their community, and they prompted him through the transfers from time to time. Through that shared dance, they amplified the community’s caring relationships.

When joy is present, we recognize the caring approach of others toward us and the need for kindness in our own approach toward others. We recognize the mutual assent within our togetherness, and the agency each of us enjoys in that togetherness. Joy isn’t a material good, but an energy found in curiosity, truth, affection, and insight. Once we recognize the radiating energy that joy brings, we will notice when it is missing and seek it out. Joy occupies those spaces where we are present and looking for the good. Like hope and love, joy is sacred.

When there is so much hate and so much resistance to truth and justice, joy is itself is an act of resistance. ― Nicolas O’Rourke

Never been to Spain, finally made it to Maine

Sam and I were supposed to go to Spain last year. We booked a cycling tour with the same outfitter that took us to Italy and Germany, and Paige and me to Ireland, over the past several years. We booked before the pandemic, but even as the lockdown began, we were thinking, naively, that with a little luck, the virus would be under control by summer, when the cycling tour would take us through the countryside around Cordoba, and into Seville and the Alhambra. Ha. Spain was being ravaged by the virus by then, and our country was on the verge of its own, first big wave. About six weeks out, the outfitter canceled the trip and refunded our money.

Sam and I biked around town last summer. It was very quiet.

When the tour catalog came for summer 2021, it seemed unrealistic to make any kind of plan to go abroad. Even the handful of U.S. tours they had, though they looked to be as much fun, felt risky. But we had to have a little faith. Our world had gotten really small. I wondered if we didn’t try to make something special happen, our mental health would suffer even more than it was. The vaccine roll-out had begun. Maybe a fall tour to see the leaves in New England could be a safe bet. Surely, the virus would be subsiding by then. Ha ha.

The company’s tours to cycle in Vermont filled up fast, so we missed that. They offered a self-guided tour of Acadia that we’d heard was good. We booked for the first week of October.

Ever since the vaccine rollout, Sam has been pushing back on letting our lives get too busy again. He wants more “thinking time” for math and signal projects he’s working on. He likes the quiet pace we found, and I agree it’s a treasure to keep. While traveling to Maine was a little discombobulating (we were really rusty with the whole packing-parking-screening thing), once we got there, it was exhilarating–as you can see below, with the boys checking the view from the Bar Harbor shoreline our first night in town:

We cycled all through Acadia National Park, learned about lobstering (and ate a lot of it), watched the stars, and got out on boat rides several times. During one nature cruise, our guide, a retired park ranger, asked how many of us would have gone abroad this year but came to Maine instead. About half of the 50 people on that boat raised their hands. Even the guide was a little surprised. Later, we visited about that moment with one of the wait staff at a brew pub who also worked part-time at the local visitors bureau. She said that they, too, had noticed many more people requesting information this year. Good for Maine.

Sam’s favorite part of the trip was that nature cruise, which took us by some of the favorite hangouts for seals, porpoises, and sea birds, including two huge osprey nests. We also saw some stunning homes along the shore. My favorite part of the trip was cycling the carriage roads through the park. They were so quiet.

Refrigerator Mother 2.0

Only a few generations ago, some doctors blamed mothers for their children’s autism. Psychologists wrote long theoretical papers based on their observations of mothers and their children. They concluded that autism mothers were cold and that their lack of love triggered the child’s autism.

If you stop to think about that idea for a minute, those explanations were quite a leap. And a cruel one at that.

We humans look for patterns in the world around us–it’s almost one of our super-powers. We use the information to make meaning, and create loops of ferocious thinking that make the world around us a little better.

Therefore, knowing that we’re supposed to make things better, the Refrigerator Mother explanation for autism just begs the question. How much did those early theoreticians consider and—most importantly, rule out—before concluding they’d observed a pattern of mothers who don’t love their children?

Granted, many people were immediately skeptical of these mother-blaming theories, including other professionals and autism families. The theories fell after a generation, but the damage was done to the families forced to live under that cloud as they raised their children.

And, the blame game is still out there.

The latest iteration has started in a similar way, with people seeing problematic patterns in autism treatment. Young adults with autism are finding their way in the world. Some of them had good support growing up, but the world isn’t ready for them. Some of them had inadequate support growing up, so they have an added burden as they make their way in a world that isn’t ready for them either. Some are speaking up not just about the world’s unreadiness but also about that burden. We must listen. Autistic voices can help us find new patterns and new meaning and build a better world for all of us.

We should be careful about letting one person’s experience and voice serve as the representation for the whole, because that’s how the blame game begins. Even back in the old days, when information was scarce, we had the memoirs of Temple Grandin, Sean Barron, and Donna Williams to show us how different the experiences can be. As Dr. Stephen Shore once said, if you’ve met one person with autism, then you’ve met one person with autism.

Here’s an example of how that can break down: some now argue that asking an autistic child to make eye contact, as a part of treatment service, is inherently abusive because eye contact feels bad for them. Missing from that argument is the basic context, the understanding that for humans to survive, we need to connect to one another. For most of us, eye contact is the fundamental way we begin to connect, from the very first time we hold and look at our new baby and our baby looks back at us.

I asked Sam recently (and for the first time) whether making eye contact is hard or painful for him. I told him I was especially curious now that eye contact changed for all of us after living behind face masks for a year. He said this, “Eye contact is very powerful. I wonder whether I make other people uncomfortable with eye contact.”

He’s right. It is powerful. And he just illustrated the point about one person’s perspective.

When Sam was young, we never forced him to look at us. But after a speech therapist suggested using sign language to boost his early communication, I found the sign for “pay attention” often helped us connect.

The additional movement of hands to face usually sparked him to turn his head or approach me or Mark in some way, so we were fairly sure we had his attention and that was enough to proceed with whatever was next. Over the years, we’ve shared eye contact in lots of conversations and tasks. But if not, we recognized the other ways that we were connecting and I didn’t worry about it.

All of this context—both the need to survive and the difficulty with a basic skill needed for that survival—cannot go missing from any conversation about the value of teaching an autistic child. Some people with autism do learn how to make eye contact early on and are fine with it. Some don’t. For this example, then, we can listen carefully to adults with autism and their advocates as they flag patterns from their bad experiences with learning to make eye contact and make changes. But that fundamental need to connect and share attention remains.

That’s when we also need to remember our tendency to blame others when our troubles feel intractable. Sometimes, in these fresh arguments over how autism treatment should proceed, I hear that same, tired pattern of blame I’ve heard since Sam was born. Take it from a worn-out mother who’s been blamed plenty over the years: some arguments are just another round of the same, they just come inside an elaborate wrapper of mother’s-helper blaming instead.

All the families I know truly love their children and are learning how best to respond to them. We can’t forget that parents have a responsibility to raise their child as best they can. Let’s talk, please. But please also, let’s spare the rollout of Refrigerator Mother 2.0, because it could cost us a generation of progress.

Vaccinating and the truth

Our extended family has been checking in with one another as we get vaccinated. We are scattered across several states, each with differing priorities and abilities to deliver the vaccine. Still, we cheer each other’s progress as we all approach the finish line.

Texas ignored essential and frontline workers in making its priorities, emphasizing shots for nursing home residents and seniors instead. Texas also got behind other states in getting shots in arms (color me not surprised). As fears rose with the fourth wave of new infections full of variants, I worried that Sam would get sick before Texas got around to vaccinating his age group.

For a while, our best hope seemed that our county was doing a good job in spite of it all. Both Dallas County (with millions of residents) and Denton County (with less than a million) have been holding mass vaccination events and both celebrated the 250,000 mark this week.

As soon as Denton County opened its vaccination list to all adults, I signed Sam up. He was at work when I did. I knew he wanted to take care of it himself, but I told him if we’d waited, even just those few hours for him to get home from work, who knows how many thousands would have gotten in line ahead of him?

The strategy seems to have worked. Sam’s appointment came the first day of the first week for the new cohort—all Texas adults. After he got his appointment, he took the unusual step of group texting his siblings and his aunties with the news. He got the high fives, but his brother and one of his aunties also reminded him that it was a shot and he would feel it.

He needed to talk about that. Sam has been accustomed to the extra steps the nurses at his regular doctor’s office take for inoculations, including applying a topical anesthesia to take the edge off. Knowing that wouldn’t happen at a mass vaccination event made him nervous. I reminded him that his brother and aunt were being very loving by telling him the truth about what to expect.

I did my best to continue the truth-telling by answering his other questions about what to expect since mass vaccinations are different. He asked me to drive him. He said he didn’t think he could manage his anxiety and drive, too. (He is not alone in that. I’ve volunteered at the speedway a few times and have seen plenty of folks shore each other up that way.)

When the moment came and the medical reserve volunteer opened the car door to administer the vaccine, he noticed Sam’s anxiety. We acknowledged it—it was the truth, after all—and he immediately shifted gears to help ease the way for Sam. The volunteer may not have had topical anesthesia, but his care had the same effect. Once inoculated, Sam said he was surprised how easy it was. The volunteer laughed and told him that applying the bandaid was the biggest part of the job. Then they both laughed.

I learned early on that it’s always better to tell Sam the truth. First of all, any child will stop trusting you if you say things like “shots don’t hurt” when you know perfectly well that they do. In addition, when Sam was little, he needed us to bridge him to the rest of the world. We couldn’t afford to be wiggly, amusement park rope bridges. Also, he doesn’t know what to do with white lies or half-truths. (Heck, they used to confuse me, too, but Sam also taught me that if you take people at their word instead of playing along, it’s their turn to be confused.)

Sam has his best shot at identifying and asking for what he needs when we tell the microscopic truth. Don’t we all?

I asked him whether he still wanted me to drive him for his second shot. Yes, please, he said.

Leap and the net will appear

Early in my career, a fellow writer and sometimes mentor said that he didn’t always know what he thought until he started writing.

That was a freeing thing to hear. The fear of the blank screen vanished. I didn’t have to know exactly what I was writing before I started. I could discover what I was thinking along the way. I could re-write again and again to make it clearer, fixing any flabby thinking and respecting the reader, because what is writing if no one reads it?

We all read to better understand what others are thinking and to adjust our thinking accordingly, writers most especially included.

Which brings me to this morning’s topic, writing to better understand a hella lotta thinking that happened this week, because this week, I quit my job.

Until Tuesday night, I had a good job that has become increasingly rare — a full-time journalist for a family-owned newspaper. The job didn’t pay particularly well, but I enjoyed the work and I was fairly good at it, so it had its own reinforcement loop that didn’t have a lot to do with money (does it ever for a writer?). I felt I was serving the community I love. I’m sure some people thought it was unnecessarily tough love at times, but I hope we can just agree to disagree there. Sorry, Charlies, sometimes the truth is really tough.

So as I climbed the hill that my job was about to die on, I was surprised at my courage to keep going. Then I saw that my feet held because they kept finding the truth. I may not have uncovered everything there was to know, but what I did know to be the truth was this: who and what was important to me might die (not exaggerating) if I didn’t keep going to the logical finish.

It’s not the first time in my life that I leapt knowing in my heart that the net would appear.

To sum up the thought for the day, I grabbed a few of my favorite lines from my upcoming book with co-author Shahla Ala’i (which luxuriously now has my full attention, a good thing because we have to deliver to the publisher in about six weeks), Love and Science in the Treatment of Autism:

Love may be the only thing that is not fragile in our material world. Love makes a great bet. Love gives our lives meaning. With love, we forge through troubles and make progress. Love makes a family. We know we will fail sometimes and that love grows in learning from those failures. Love helps us through periods of being unlovable ourselves, or of not loving others.

We keep choosing love, above all.

Wear an Apron

This year marks my fourth year of pursuing New Year’s resolutions that are, at once, both big and little.

When I started out, I shared my first goal (not buying anything except food and to fix things, aka “No, Thank You”) with a few close friends and family members. Sharing your goals publicly usually increases your chance for success. For the second year, I straight up wrote a column in the newspaper. Honestly, that felt more like raising the stakes than getting a leg up, but it worked (“Yes, Please” to new experiences and long-held aspirations). This January, I quit Facebook in order to make 2019 the year of being more open and connected.

Over the past 12 months, I found myself being even more deliberate with treasured relationships, traveling a surprising amount in pursuit of that goal. Just like the years of “Yes, Please” and “No, Thank You,” a Facebook-free life can totally be “More Open and Connected” when it’s more deliberate.

This year’s goal is “Wear An Apron.” My son, Michael, and I talked it over on a recent Sunday together. He wanted to know what the big idea was behind the little idea.

I have two kitchen aprons. One I picked up at the farmer’s market in Sacramento because it says “California Grown” on it. The other my mother made for me out of fabric she picked up in Hawaii. They are both awesome and spark joy for me. But I nearly always forget to put them on until after I have already spilled something on myself.

My T-shirt drawer is full of shirts marked by my forgetfulness. I tell myself that they are just T-shirts, but the truth is, I am capable of better.

And that’s the thing about aprons. Some amazing person solved a common problem by inventing the apron. And other smart people figured out designs with pockets and loops and other features to help your apron serve you, whether you are in the wood shop or the kitchen or the printing press.

I told Michael when you think about the apron that way, it reminds you that most problems you experience have been solved by someone already. That wisdom, both small and large, is out there and ready to make life easier or better. It’s something your grandfather discovered long ago or is in a book or on YouTube or just one question away in a conversation with a friend.

Even when Sam was little and it seemed like no one knew anything, the wisdom was out there. I’ll forever be grateful to Kitty O. for showing me how to read articles in scientific journals. New wisdom. Right there.

All you need to do is put on that apron.

Let there be dancing

As important as dancing is to Sam’s social life, I’m a little surprised that I haven’t blogged much about it before.

Last weekend, Michael and Holly got married. Sam was the usher. He enjoyed dressing the part and hanging with the groomsmen, but I think he looked forward most to the dancing. During the reception, the DJ spun a wide variety for us. We two-stepped and did the mambo to a salsa tune, and more.

The television show, Dancing with the Stars, was Sam’s favorite for the longest time and he would try to do some of the moves when he thought I was out of the room.

I don’t know how I stumbled on the east coast swing dance club in town, but after I did, I planted the seed that he could join and learn more. It took a little while for Sam to warm up to the idea. After he’d gone once or twice, I asked Michael and Holly to go with him once and make sure everything was ok. (It was.) Over time, I’d hear from neighbors, friends and acquaintances about how well he was coming along. He goes at least twice a month, including asking off work for the Friday night dance that includes some extra lessons.

Michael and Holly had a dollar dance over several tunes during the reception last Saturday. Sam queued up twice with ten-spots to dance with Holly. I was ready with the video for the second dance, but as you can see, the kids got silly and they were upstaged a wee bit.

After the DJ’s “last dance” call, they had just one more: Bruno Mars’ Uptown Funk. It’s just about Sam’s favorite tune of all time. The kids all got in a circle and started their dance-off. Sam was second in the ring, and the crowd just lost it when he entered and danced his moves. There is video out there in the wild somewhere, y’all, but I don’t have it. (If it surfaces and I can publish it, it will be here. I’m not sure the official wedding videographer got there in time.)

Let there be dancing.