health

A lot of slop and wobble

The words about to unfold below weren’t exactly how I planned to start or end this post. The house is quiet and Sam is likely napping. We just finished a Sunday bike ride down the rail trail, which felt a little like a victory lap today. On Monday, we rode the trail all the way to Lewisville Lake so we could get a good, long time with totality.

(That supposed life hack of holding solar glasses to your smartphone to shoot the eclipse? I stopped trying to take photos after this shot. I cherish the images in my memory. It was an unparalleled life experience–babies being born, totality, etc., etc.)

Today’s victory lap was marred by a motorist who chose the moment he passed us (we were waiting at the McKinney Street crosswalk by City Hall) to lay on his horn a good long time. A few motorists have done that to us in the past. Each time, as the adrenaline shoots through you, it feels a bit like someone punched you in the face.

Whether honking a horn like that should be considered assault may feel like an open question. Yet Sam’s reaction today, as in the past, convinces me that it is. He’s a beast of a cyclist, but after the horn, he took off like a cheetah. He was already through Quakertown Park and halfway down Congress Avenue by the time I got to the little bridge over Pecan Creek.

For the rest of the ride home, he’d pedal at incredible speeds and have to circle back to meet me before taking off again. I can’t imagine how much adrenaline is coursing through a person’s body that it takes more than two miles of fast pedaling to work it off. During one circle back, he said to me, “I’m a good person. But it doesn’t matter to him. That’s why I can’t feel safe.”

Risk is always with us. It’s hard to calculate sometimes. I borrowed today’s headline from a Washington Post story about calculating Earth’s rotation. I never doubted the math for the eclipse, which takes into account the slop and wobble of our little orbit around the sun. It was marvelous to sit on the lakeshore Monday, looking up through solar glasses to watch the eclipse start and progress and make the world go dark, just like they calculated.

A lot of modern life takes all this elegant math for granted. We need to remember that the world may speak in calculus, but life is not precise. What makes some math so elegant is that it hasn’t forgotten about all of life’s beautiful slop and wobble.

I suppose we could stop riding bike, but that’s no way to address the risk. Or we could insist that police ticket motorists for assault when they use their horns that way, but that introduces other risks.

Or, maybe I could write an essay about life’s slop and wobble, sending a little message out into the world that asks everyone to please be kind to all cyclists, because you don’t know which ones might be autistic.

Small, little men

The national media is noting the ignorance and cruelty in Texas public policy, including the new laws that ban abortion and suppress voting rights. I would argue that the state’s policies and governance vis-à-vis people with disabilities amply demonstrates that this ignorance and cruelty isn’t new.

Elected officials in Texas have refused for years to adequately fund the medical and disability services that allow individuals to live in the community and avoid costly (especially to taxpayers) institutional care. Federal programs can pay the lion’s share of these services, and in most other states they do, but Texas refuses to expand Medicaid enough to allow that to happen. Instead, they authorize puny levels of funding for “waiver” programs—part of the federal law that allows Texas and other states to opt out with the promise to take care of people in their own way. But really what Texas does is pretend the burden doesn’t exist. Instead of fostering human progress, Texas disability policies hardwire families and communities for long-term suffering.

Sam was in kindergarten when we first moved to Texas. We followed the advice of the good people at Denton MHMR and put his name on one of the infamous waiting lists for the state’s waiver programs. Our social worker said that even though we couldn’t be sure then what services Sam might need when he was 18, we’d have no chance at help if he wasn’t on a waiting list. At the time, we were among the young families that got a little help paying for respite care and for special equipment, so we picked the waiting list for the waiver program most like that.

(Sadly, a year or two later, even that modest state program for young families ended. We were on our own.)

Families who are able to access services under these sparsely funded waiver programs understand them much better than I do. Sam made enough progress and adapted well enough that he doesn’t need the help—the kind of basic human need that tends to make allies and advocates into battle-hardened experts in the shortcomings of public policy.

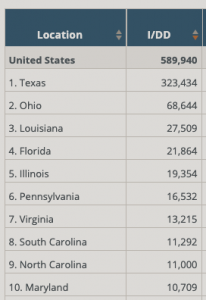

But I do know that the Texas waiting lists for waiver programs are cruelly long. Nationwide, there are about 600,000 people on a waiting list and more than half of them are on a list in Texas. (For context, remember that less than 9 percent of the nation’s population lives in Texas.)

In its latest budget, the Texas Legislature funded additional slots to get more people into the waiver programs, but not nearly enough. Some advocates and self-advocates have done the math: the Texas list is so long that individuals could wait their whole lives and never receive services.

When other states would get in this deep, they agreed to Medicaid expansion made possible by the Affordable Care Act. Waiting lists for waiver programs in those states nearly disappeared because Medicaid expansion stepped in to fund those services.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Texas is among just 12 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. Texas is, by far, the most populous state to refuse to provide services at a meaningful level and make no real progress toward that goal.

Some advocates wonder whether the U.S. Department of Justice will intervene, especially when U.S. Department of Health and Human Services officials seemed to wobble on approving the state’s waiver program earlier this year. It’s a great question, but we need look no further than the state’s troubled institutions—called state supported living centers—to see how a negotiated settlement might go. Independent federal monitors have visited those centers since 2009, after fresh reports of abuse and neglect emerged with cellphone video of a “fight club” forced on residents at the Corpus Christi center. All 13 centers were supposed to meet negotiated standards by 2014 or face further action, up to and including closure. Twelve years later, none of the centers (home to about 4,000 people with developmental disabilities) met the standards, the monitors still make regular visits, and all 13 centers remain open at increasingly unsustainable costs to state taxpayers.

Texas is growing fast and its people need a far more robust physical and social infrastructure than state officials seem to grasp. Some people see our governor moving about in a wheelchair and think he’s got the disability thing covered. But advocates know better. “He’s not one of us,” I heard one self-advocate say recently, pointing out the many, many differences between an individual who must adapt their entire life when compared to the governor’s experience, where the need for a wheelchair came much later in a life of privilege.

These days, Texans are watching their governor and the other small, little men in state leadership race to the bottom in a panic to maintain power. In that twisted race, their lawmaking and policies are displaying new levels of ignorance and cruelty for all to see. But color me not surprised, as the ignorance and cruelty has been part of their law- and policymaking for our community for a very long time.

Vaccinating and the truth

Our extended family has been checking in with one another as we get vaccinated. We are scattered across several states, each with differing priorities and abilities to deliver the vaccine. Still, we cheer each other’s progress as we all approach the finish line.

Texas ignored essential and frontline workers in making its priorities, emphasizing shots for nursing home residents and seniors instead. Texas also got behind other states in getting shots in arms (color me not surprised). As fears rose with the fourth wave of new infections full of variants, I worried that Sam would get sick before Texas got around to vaccinating his age group.

For a while, our best hope seemed that our county was doing a good job in spite of it all. Both Dallas County (with millions of residents) and Denton County (with less than a million) have been holding mass vaccination events and both celebrated the 250,000 mark this week.

As soon as Denton County opened its vaccination list to all adults, I signed Sam up. He was at work when I did. I knew he wanted to take care of it himself, but I told him if we’d waited, even just those few hours for him to get home from work, who knows how many thousands would have gotten in line ahead of him?

The strategy seems to have worked. Sam’s appointment came the first day of the first week for the new cohort—all Texas adults. After he got his appointment, he took the unusual step of group texting his siblings and his aunties with the news. He got the high fives, but his brother and one of his aunties also reminded him that it was a shot and he would feel it.

He needed to talk about that. Sam has been accustomed to the extra steps the nurses at his regular doctor’s office take for inoculations, including applying a topical anesthesia to take the edge off. Knowing that wouldn’t happen at a mass vaccination event made him nervous. I reminded him that his brother and aunt were being very loving by telling him the truth about what to expect.

I did my best to continue the truth-telling by answering his other questions about what to expect since mass vaccinations are different. He asked me to drive him. He said he didn’t think he could manage his anxiety and drive, too. (He is not alone in that. I’ve volunteered at the speedway a few times and have seen plenty of folks shore each other up that way.)

When the moment came and the medical reserve volunteer opened the car door to administer the vaccine, he noticed Sam’s anxiety. We acknowledged it—it was the truth, after all—and he immediately shifted gears to help ease the way for Sam. The volunteer may not have had topical anesthesia, but his care had the same effect. Once inoculated, Sam said he was surprised how easy it was. The volunteer laughed and told him that applying the bandaid was the biggest part of the job. Then they both laughed.

I learned early on that it’s always better to tell Sam the truth. First of all, any child will stop trusting you if you say things like “shots don’t hurt” when you know perfectly well that they do. In addition, when Sam was little, he needed us to bridge him to the rest of the world. We couldn’t afford to be wiggly, amusement park rope bridges. Also, he doesn’t know what to do with white lies or half-truths. (Heck, they used to confuse me, too, but Sam also taught me that if you take people at their word instead of playing along, it’s their turn to be confused.)

Sam has his best shot at identifying and asking for what he needs when we tell the microscopic truth. Don’t we all?

I asked him whether he still wanted me to drive him for his second shot. Yes, please, he said.

Pandemic and the after times

Hopefully, this week tips the balance between the number of people Sam and I know who got sick with COVID-19 (a lot) and the number who’ve been immunized (only a handful). Texas has lagged the rest of the country in delivering vaccine, and our county has lagged even further, at least until they organized this week’s 10K-per-day, multi-day, drive-through shot clinic at the speedway.

The pandemic forced Sam and me to reshape our lives quite a bit over the past year, and the routine that evolved likely helped our mental health. We took a few days at Christmas to visit Michael and Holly in Austin (combining our bubbles proved just fine) and found that, in coming back home, re-establishing the daily rhythm took a little effort. We thought our routine was a gentle one, but it was a routine nonetheless.

Now, we can see that the routine will change again as the pandemic recedes. Sam says he finds it hard to imagine that things will go back to the way they were, even though he would like to go dancing again and some horseback riding competitions could return. Those leisure activities mean taking time off work, something he’s done very little of in the past year.

In addition, we like much of what we’ve folded into our lives since the pandemic shut us in. We found time to learn calculus, which has become a small, joyful part of nearly every day now. We also look forward to bike riding on the weekend. (We signed up for a virtual challenge because, first, his sister suggested it, and second, because it seemed like a peak pandemic-y thing to do.) And Saturday night has become movie night for us in a way that Alamo Drafthouse couldn’t replicate, snacks and all: we set the schedule and we curate our own themes. Right now, we are watching films that explore civil rights and our country’s dark history of white supremacy.

Many new things we do may continue, including the favorite parts of our routine. Sam says he will continue wearing masks for allergy season or whenever he needs to protect himself from dust. I suspect we may don them in public other times, too. It’s kind of gobsmacking how, in the before times, we were expected to go to work with a cold, or otherwise be out and about and infecting each other. Egad.

In other words, I don’t think it’s just the family dog who’d rather we keep the current routine. Maybe that old routine from the before times wasn’t so free after all, subjecting us all to much more of a rigid and unhealthy grind than we remember.

Wear an Apron

This year marks my fourth year of pursuing New Year’s resolutions that are, at once, both big and little.

When I started out, I shared my first goal (not buying anything except food and to fix things, aka “No, Thank You”) with a few close friends and family members. Sharing your goals publicly usually increases your chance for success. For the second year, I straight up wrote a column in the newspaper. Honestly, that felt more like raising the stakes than getting a leg up, but it worked (“Yes, Please” to new experiences and long-held aspirations). This January, I quit Facebook in order to make 2019 the year of being more open and connected.

Over the past 12 months, I found myself being even more deliberate with treasured relationships, traveling a surprising amount in pursuit of that goal. Just like the years of “Yes, Please” and “No, Thank You,” a Facebook-free life can totally be “More Open and Connected” when it’s more deliberate.

This year’s goal is “Wear An Apron.” My son, Michael, and I talked it over on a recent Sunday together. He wanted to know what the big idea was behind the little idea.

I have two kitchen aprons. One I picked up at the farmer’s market in Sacramento because it says “California Grown” on it. The other my mother made for me out of fabric she picked up in Hawaii. They are both awesome and spark joy for me. But I nearly always forget to put them on until after I have already spilled something on myself.

My T-shirt drawer is full of shirts marked by my forgetfulness. I tell myself that they are just T-shirts, but the truth is, I am capable of better.

And that’s the thing about aprons. Some amazing person solved a common problem by inventing the apron. And other smart people figured out designs with pockets and loops and other features to help your apron serve you, whether you are in the wood shop or the kitchen or the printing press.

I told Michael when you think about the apron that way, it reminds you that most problems you experience have been solved by someone already. That wisdom, both small and large, is out there and ready to make life easier or better. It’s something your grandfather discovered long ago or is in a book or on YouTube or just one question away in a conversation with a friend.

Even when Sam was little and it seemed like no one knew anything, the wisdom was out there. I’ll forever be grateful to Kitty O. for showing me how to read articles in scientific journals. New wisdom. Right there.

All you need to do is put on that apron.

Saturday night in the kitchen with Sam

Over the years we have made a true commitment to our family’s health by doing a lot of cooking and baking. Tonight, I’m making another batch of yogurt and Sam is making kolaches.

I had enough variety of leftover beans from a bunch of winter cooking to make a mixed-bean soup, too.

Over conversation about tablet computers, e-reader apps, and area equestrian Special Olympics (they moved it up to today instead of tomorrow … awesome flexibility demonstrated by area stables in order to avoid predicted storms), I put this old family favorite together, substituting in lamb stock for water at the end.

Bountiful Bean Soup

2 cups mixed beans

1 quart water

4 slices of bacon, diced

1 large carrot, sliced

1 clove garlic

1 bay leaf

6 cups water

Salt and pepper to taste

Bring beans and first quart of water to a boil. Cover and let stand for an hour. Drain and rinse a little. (This helps reduce your need for Bean-o)

Fry bacon in a dutch oven and discard all but 2 t. of the rendered fat. (Or, leave out the bacon and heat 2 T. of olive oil.)

Add the carrot and garlic and saute for a few minutes to carmelize, then add beans and water and bay leaf. Bring to a boil and then reduce to a simmer, cooking for 90 minutes or so until the beans are tender.

Remove bay leaf, taste and add salt and pepper to taste.

Probiotic Potion Master (in training)

I wish that the amount of awareness and research into autism and the gut was part of our lives when Sam was a baby.

I can’t help but think things would be different. I touched on some of the problems that emerged when he was a toddler in See Sam Run. But there was never, ever any kind of meaningful conversation with his pediatrician until he reached his teens.

By then, Sam’s food preferences could just as easily fall into the category of an eating disorder as be seen for what they likely were — an adaptation to what gave him bellyaches on a scale that I don’t think the rest of us could tolerate.

But Mark and I were ready to take out a second mortgage on the house so that Sam and I could spend the summer at an in-patient treatment program at Ohio State when Sam was 14 or 15 years old. Sam had shot up at that point, but he wasn’t eating meat. He looked every bit as undernourished as he was, especially his skinny little quads and calves. The program helped get kids with autism to expand their eating choices. Another parent on the autism journey whom I really trust had recommended it.

Fortunately for us, the treatment director recommended that we rule out Celiac disease before we got there, since that was something they typically did before they started treatment anyways. Sam couldn’t eat any gluten for a week before the blood draw, and he got really hungry.

He decided he could eat meat after all. He like sausage the best. He also figured out ways to taste and try new things to decide for himself whether he liked them. We decided that was enough of a breakthrough not to hock the house.

Even though they were able to rule out Celiac, the test results hinted at trouble. We talked about it, but there really was nothing more to be done, the doctor said.

When it was time for him to transition from his pediatrician to the family physician, she asked me if I had any concerns for him. Again, I tried to open the door to talk about his digestive troubles. She said she didn’t know anything about it and that was the end of that.

The issue has re-emerged for him and this time we are going after it a lot more informed. When he was a preschooler and would only eat cereal morning, noon and night, we fortified his milk with l. acidolphilus. I’d always made yogurt over the years, although Sam wasn’t always a big fan. We had some inkling of what needed to be done to help his digestive system, but we didn’t know to what degree.

My first hint, honestly, that there was a much, much bigger world of beneficial bacteria out there was when my daughter, Paige, started making us kimchi and told me it was a health food.

Light bulb.

So, now we are all about the fermenting here at the Wolfe House. I started with Creole cream cheese. I tried not to channel my home economics teacher as I sat that milk out on the counter for a day and half. But it was wonderful. I made crepes and filled them with the cheese topped them with warm strawberry jam. Sam likes cheesecake so I thought it wouldn’t be too much of a reach, but it was. Oh, well, more for Michael and me.

Plus, I had a whole bunch of the kind of whey the author of Mastering Fermentation likes to use in her recipes. Next up was probiotic ketchup (a hit) and hummus (good, but a miss for Sam.)

When we make our salad dressings now — Sam is a huge salad fan — we use vinegar with the mother. (Just Google it. The point is to eat food that’s alive.)

Judy Thurston over at Hidden Valley Dairy suggested keifer (another hit) and I just ordered supplies I need to make soy sauce and regular cream cheese.

I want to get good at making cheese so that I can make the one he loves: Parmesan.

I’m still working on getting supplies for what I’m sure will be a big hit when I get it done: salami.

I’m still working on getting supplies for what I’m sure will be a big hit when I get it done: salami.

No kidding, it’s fermented. Is that why sausage was the breakthrough for him 10 years ago?

Well, back to the kitchen. Got more potions work to do.

Remembering a visit to the E.R.

Researchers have come out with a protocol for emergency room personnel who find themselves caring for a person with autism. I’m glad to see this.

In January 2009, I took Sam to the emergency room in the middle of the night.

He got a bladder infection. He came home from the first day of competition at Chisholm Challenge and was passing blood, which alarmed him. I told him we’d skip the second day of competition and see a doctor in first thing in the morning. But, he woke me up at 2 a.m., shaking uncontrollably and a little panicked.

Even though he’d just turned 21, the pediatrician was still his primary care doctor. So I phoned the nurse on call. Because he was exhibiting signs of shock, she told me to take him in. By the time we got there, he had stopped shuddering, but his urine sample was brown.

We’d gone to Baylor-Grapevine, which was a fairly new hospital at the time. He was already familiar with it because an occupational therapist working out of the rehab center there helped teach him to drive. (Big shout out to Cathy.)

I remained concerned. Would it be filled with people? Would the sounds of arriving ambulances distress him? I was worried most about the staff. Would they be brusk and stand-offish? Would he be hustled around? I didn’t have time to prep them the way I had prepped the many other doctors, dentists and health care givers in his life.

With the first interaction, I saw the lightbulb go off in the ER nurse’s head. She immediately adapted. And everyone who followed after her knew to take their time, be calm and explain each step.

We were lucky, too, that it was a quiet night. The visit wasn’t much different from one at a doctor’s office, except for reams more paperwork and the occasional paramedic tromping down the hallway.

Here’s what the research recommends and what I noticed the folks at Baylor-Grapevine already knew to do:

· Usher patients to a quiet, more dimly-lit room with less equipment

· Avoid multistep questions and stick to questions that require only a “yes” or “no” answer

· Communicate with the care giver or family member, if one accompanies the patient, to get an effective medical history

· Keep voice calm and minimize words and touch

· Let patients see and touch the instruments and materials that will be placed on their bodies

· Use a warm blanket to calm a patient down and administer mild doses of medication rather than physical restraints to quiet a patient

Parenting is a contact sport

Some people like to claim their gray hair comes from things their kids did. I see my scars and remember.

I have a long skinny scar that runs from knuckle to knuckle on my ring finger that came while digging in the garden with Michael. He felt so badly when he saw that his little shovel missed its mark and drew blood.

I was surprised how strong he was.

I’ve got a knot on my forehead from trying to help build a fence for the cashmere goats, a 4H project that lived here for 5-6 years. I got clubbed so hard by a round of woven fence wire that was hung up on a t-pole — almost spring-loaded, like a giant mousetrap — that it should’ve killed me. But the kids were all standing there, so I told myself to take the hit and keep on ticking.

Today I went to work with an odd-looking burn on my chin, like a permanent dribble of hot chocolate. I thought for sure at least Bj would say something, but no one asked.

Last night, Sam was determined to learn how to cook fish tacos. He dropped in the first battered fish strip from such a height, the frying oil splashed. Sam got a few splashes on his arm and I took one on the chin. But by the third strip, he was dropping it in perfectly.

Like Jason Robards character said in Parenthood, parenting is “like your Aunt Edna’s ass. It goes on forever and it’s just as frightening” and is unlike football, since there’s no end zone where you get to spike the ball and do your little dance.

Except he missed the part where parenting is a contact sport.

Country cough syrup

Up north, we just bought cough syrup. It works well enough. Then I came to Texas and my college roommate and BFF introduced me to country cough syrup. It works and, like chicken noodle soup, does a whole lot more for your quality of life when you’re feeling bad.

In case you don’t know the recipe, here it is, and offered up for all the people around here still sick with the flu, or fighting a lingering cough (as in about 1/3 of the newsroom):

Brew one cup of black tea. (I like Earl Grey for this one). Add a squirt of lemon juice, a heaping teaspoon of honey (local is best), and a shot of Wild Turkey, or your favorite bourbon.

Drink slowly so the vapors can do their work, too, and then go to bed.