Random thoughts on running the Grasslands Half

The same wet weather that makes trail races around Grapevine Lake too soft and too muddy makes running the grasslands just right. Sand for horses packs nicely after a good rain. Some horses don’t like the sound of your approaching footsteps, no matter how much you slow down. Trail runners are a smart bunch and share good advice with each other, and that’s how I knew to fuel up at the last stop. But they also sometimes forget to follow directions instead of the runner in front of them. Follow the blue flags is especially important when the trail comes with a bypass that makes the race longer than advertised. Missing birdsong makes the grasslands eerie quiet and plays mind games and makes you think

there’s a cougar watching. Having more than one goal for finishing grasslands is good. Recently, I decided that not falling down is a good goal. Mission accomplished.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #316

Sam: What’s an ‘old-timer’?

Peggy: I think different people might use that label to describe different things. What do you think it means, Sam?

Sam: Someone who doesn’t use new technology.

Peggy: Oh yeah?

Sam: And someone who talks about the old days.

Peggy: Then I guess I’m not an old timer.

Sam: Really?

Overheard in the Wolfe House #315

Book report

Over the past ten days, I went back to read a book that had been recommended many times but I hadn’t until now: Clara Parks’ The Siege.

Her book is a parent memoir, but in a class by itself. If I had read her book when Sam was first diagnosed, many pages would have been dog-eared and worn for her wisdom. Parks was an English teacher at Williams College and had her master of fine arts degree. In other words, she knew the value of keeping a daily journal, and thinking critically about what was happening in her family, and applying what she knew about language — and how it was different for her daughter, Jessy (Elly in the book’s first edition) than her other, older children.

I was struck by how many experiences we had in common. Both Sam and Jessy proved their intelligence in unusual ways, which required their families to pay attention. They both kept elaborate maps in their head that allowed them to return to a place even if they’d only been there once.

Both Sam and Jessy also had distressing episodes with vomiting.

And I will digress at this moment to say that researchers have been far too slow to try to understand this problem. Many, many parents report their young children with autism have distressing digestive problems. Parks wrote about her daughter’s in 1967; it’s not like researchers can say they were surprised. Parks gave the problem enough ink that the skeptical reader knew her own theory about the mystery was just that. But, as far as I can tell, it wasn’t until Andrew Wakefield’s disgraceful paper in The Lancet that funders and scientists got serious about understanding digestive problems that children with autism have. Besides faking his numbers to gin up the vaccine connection, Wakefield went into that vacuum of knowledge about autism and digestive problems to give his idea that same sticky quality you find in urban legends.

A publisher once told me that he gets pitched a lot of parent memoirs. He doesn’t publish them any more. They don’t sell. That’s sad. It’s not that Parks’ memoir is the be-all-end-all (although I suspect that if I’d read her book as a young mother, I would have been too intimidated to write one of my own.) But I don’t think we’ve even begun to scratch the surface about what parents have observed, and what that might mean for furthering scientific understanding.

For example, Parks’ observations about language were stunning. Speech pathologists likely understand more about language development in children with autism than they did in 1967, but there’s just too much thoughtful description in her book for me to believe that they’ve got it all.

It’s true that it doesn’t have to be a memoir. Maybe there’s another way to capture all those stories and wisdom to make it better for the next generation of parents and children.

The Grand Tour

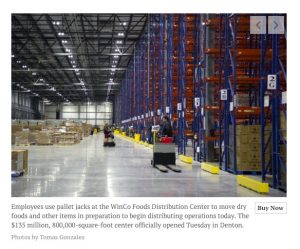

I missed the big day when the WinCo warehouse had its open house almost two years ago. Michael and Paige went with Sam, and got to see where Sam had trained as well as the spot where he works inside that massive building.

Sam will celebrate his second anniversary with the company in March. A few days ago, I took part of the day off to ride to work with him and finally get a tour of the place.

(Here’s a news story from the opening, shown in the Denton Record-Chronicle photo shown above.)

Sam’s unit unpacks small dry goods, such as shampoo and lotion, that are continuously delivered to the warehouse. They move them into bins that can be quickly accessed for shipment to stores in the region. (Sometimes he works on that repacking side, too.) They keep about 18,000 inventory bins stocked at all times. Much of the work is automated, which means he’s working with computers and all kinds of lifts and conveyors.

Once they’ve unpacked a delivery box, they throw the empty box up on a conveyor to the cardboard compactor, which was the highlight of the tour for my inner 8-year-old. The grown-up in me nearly melted watching his face light up showing me how it all worked. He is clearly enjoys his job, and is good at it — his supervisors told me as much, too.

When Sam first joined the workforce almost 15 years ago, a dear friend in the rehab department at the University of North Texas told me that Sam would learn and grow a lot on his first job. I was so grateful that he told me that, because I knew not to be surprised, and to be alert and responsive to those changes. I remember how challenged I felt entering the work force (a feeling that returns with each new job, and sometimes each new assignment, honestly), but I wouldn’t necessarily have connected to those experiences and been ready to help Sam in reinforcing his growth and understanding all of his new experiences, rather than being bewildered by them.

For example, I told him he might be surprised at how tired he would feel going from part-time to full-time work, especially such physically demanding full-time work. He was happy I shared that experience. After a few months, he was ready to advocate for himself in a powerful way: to get moved to swing shift. He knew he was not a morning person and that he needed more rest than he was able to get working day shift.

He also gained a lot more confidence in his strength. I don’t know what it is about autism, but it seems like lots of kids with autism don’t grow up with the core strength that most neuro-typical kids have. Horseback riding probably helped Sam get stronger than he was initially wired for.

But I knew WinCo put that over the top when I asked him to help me load a dryer on the back of my pickup, the kind of two-person job we had done many times over the years. I planned on taking the dryer to my girlfriend in Houston, who’d been all but wiped out by Hurricane Harvey’s flood waters. After I put down the tailgate and anchored the ramps, I turned around to see that Sam had already loaded the dryer on the dolly. He walked it all up the ramp without a word, like the grown-ass man he is.

The Power of Parmesan Cheese

Sam was very young when he discovered that Parmesan cheese made almost anything taste better, and it became a thing in our family.

We would tell the wait staff at Olive Garden, for example, to please leave the twirling grater at our table, because they had other tables to tend to and they didn’t need to spend all their time grating cheese for us.

(Now, foodie friends, please don’t judge. We were thrilled that (1) Sam finally could not only tolerate but enjoy a dinner out with the family and (2) the kids were asking to order things beyond a hamburger and fries.)

When Sam was little, he had distressing vomiting episodes. The doctors were no help. He eventually whittled his food choices to cold breakfast cereal with milk, morning, noon and night.

After a few years, we stumbled on the power of Parmesan. For Sam, the cheese was a gateway to trying other foods. Parmesan helped restore a balanced diet for him, including vegetables and salads. We didn’t blink at the amount of Parmesan that flowed. We even bought a twirling grater. On our family vacation in Germany last summer, we came across cheese mongers selling massive wheels of Parmesan and we teased Sam, “dude, that’s what you need to buy for a souvenir.”

I used to liken his preference to the way some people think everything tastes better with a little ketchup or mustard. For Sam, it was Parmesan, and we figured that was that.

Then along came Samin Nosrat and Salt Fat Acid Heat. In her Netflix series, she talked about the first time she was a guest at a traditional Thanksgiving dinner and how she found herself slathering the cranberry sauce on everything because the meal lacked the acid her palate craved.

Then along came Samin Nosrat and Salt Fat Acid Heat. In her Netflix series, she talked about the first time she was a guest at a traditional Thanksgiving dinner and how she found herself slathering the cranberry sauce on everything because the meal lacked the acid her palate craved.

In the episode in Italy, she spent considerable amount of time exploring how Parmesan cheese was made and what powerful things it can bring to a dish–fat, acid, salt. She told viewers that good Parmesan should be among your kitchen staples.

No worries, Samin. We got a big check mark on that one in the kitchen at Chez Wolfe.

Horsemanship as culture

When we first moved to Texas from California, I was struck by the fact that Fort Worth’s cultural district put world class arenas and art museums side by side. At the time, I thought we would be more frequent visitors of the latter. That was upside down.

Watching Sam’s ride in “working trail” events, you can see how many cultural conventions there are in horsemanship. Some of them I understand. Some of them I don’t. Sam learns what’s expected of him as a horseman without a lot of extra chatter, which in itself is a cultural convention.

He does well with this pattern, but his horse, Smut, resists him at the gate. He keeps at it until the judge times him out. I’ve watched him persist at the gate before. He shows unlimited persistence when there’s no time limit. When I start unraveling in front of a problem, I remember how he persisted as a baby, toddler, student — including college — and somehow all the frays just go away.

Making some dust

There aren’t many horseback riding events at Chisholm Challenge where the riders go as fast as they can. Sam hasn’t been barrel racing long, but he’s got the hang of it.

There were several other riders in other classes that raced before Sam’s class. (Riders completed the course at a walk, a jog or a lope. Sam was in the loping class.) I saw more than one rider come out of the gate and go straight into their trot, so I joked with one of Sam’s coaches that he should ‘haul ass’ when they opened the gate, just like the women who gallop through the pattern in 15 seconds in the professional rodeos. She thought that was pretty funny, so she grabbed her cellphone and called her husband, another of Sam’s coaches, and told him so.

I don’t talk to Sam that way, so we were all having a good laugh. But when they opened the gate, he went for it, too. The judges threw a flag because the volunteers with the stopwatches weren’t ready.

I worried that my joke got him disqualified, but they let him go again from the rail.

He won his class with an “official” time of 0:34. He’s riding Smut, representing Born2Be Therapeutic Equestrian Center. Enjoy.

Internet commerce is a wild web

If Sam wrote up his tips for how to avoid getting scammed, it would read something like this.

- Don’t read email

- Don’t respond to texts

- Don’t answer the phone

- Open snail mail only after your mom nags you for a week that it’s important

And still things happen to him. I try not to hover. He’s a grown-ass man. He managed to handle something this week that would make Dave Lieber and his Watchdog Nation proud: he got a refund from a seller on eBay.

Sam is working on backing up his computers cloudlessly. It means he needs some external hard drives, and some redundancy. It’s a good project for him. One of the devices he bought for the project wasn’t the right device. He sent it back to the seller. He got proof that he sent it back and the seller received it. But the seller was very slow in refunding his money. It was a lot of money–$120 or so. He complained to eBay and then he went over to his bank to see what they could do. This is where I give a big shout-out for the power of local banks who get to know their customers, because they helped turn up the heat with PayPal. Sam announced this morning that eBay is refunding his money.

Sam said, “I was starting to think that the seller wanted to sell me the wrong item and keep my money.”

That’s an excellent demonstration of being able to take the perspective of another and act accordingly, something that is hard for people with autism to do.

I told him that eBay and other e-commerce platforms need sellers to be honest or their platform becomes irrelevant. I used to not tell Sam things like that. But, he’s getting the hang of this seeing-situations-from-another-person’s-perspective thing.

He still wants a better consumer tip sheet, and he’s got a point. When he was at the bank, he learned about “verified sellers.” In the 23 years eBay’s been around, I think I’ve bought two things on that platform. I really have no idea. I’ve got my homework for the week.

And, if anyone has good consumer tips about eBay, please leave them in the comments below.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #314

Peggy: That box on the front seat of your car is all your old ribbons to take to Mary’s office next time you ride at Born2Be. They can reuse them.

Sam: Yeah, Mom, it takes more than a ribbon to prove your success.

#RealMillennial