problem-solving

Lessons of calculus

Sam didn’t learn calculus in high school and has decided, now that he’s in his 30s, that this deficit in his education must be remedied – not just for him, but for me, too.

I was a bit of a math whiz in junior high and high school, and while I didn’t get much calculus instruction either, I was somehow destined to review algebra, geometry, and trig lessons at least once a decade as the kids grew up and as Sam struggled with advanced algebra classes in junior college. To share in Sam’s enthusiasm for this new endeavor, I picked up Steven Strogatz’s book, Infinite Powers. It’s a persuasive little tome about the secrets of the universe and the author has nearly convinced me that God speaks in calculus. (And, perhaps that is why we have a hard time understanding Him.)

Sam doesn’t need all that. He just wants to master the principles and formulas (Hello, Kahn Academy) to break free of the limits he feels in his amateur music and sound studio, acquiring the demigod ability to manipulate the sound waves his computer produces.

Sam and I have been chipping away at this calculus thing for several weeks, beginning with a thorough review of the fundamentals. We know you can’t do the fancy moves until you’ve got the basic blocking and tackling down cold.

Through this journey, I’ve watched Sam learn a lot when we make mistakes. Kahn Academy tutorials ring a little bell and throw confetti every time you get an answer right. We don’t stop and think about how we nailed it. However, get the answer wrong and we are motivated to go back to find the missteps. Somehow, examining that failure locks in the learning just a little deeper.

Some writers and thinkers dismiss the fandom that failure gets in the business community. (Failing Forward! How to Fail like a Boss!) They are right: platitudes can’t turn failing into big money and success. That whole ready-shoot-aim philosophy just gets you muscle memory for ready-shoot-aim, in my experience. Examining your choices and, importantly, your knowledge deficits before making changes is what gets you back on the path of progress.

When I was in graduate school at the Eastman School of Music, some of us sat for a short, informative lecture from brain researchers at the Strong Memorial Hospital (both the school and the hospital are part of the University of Rochester). They showed us how the brain looks for motor patterns in the things that we do (walking, for example) and then files those patterns with the brain stem once established. It makes our learning and doing more efficient. But, of course, for practicing musicians, that tendency is a terrifying prospect. Practice a music passage wrong often enough and your non-judgmental brain says, “Aha! Pattern!” and files it away for safekeeping. The last thing you want is for that incorrect pattern to trot itself out when you are stressing. That’s how mistakes happen in a big performance. And they do. All. The. Time.

Sam and I are doing our best to go slowly and learn how to work the principles and formulas right the first time, or at least going back to retrace our steps when we trip up so we walk it through correctly on the second pass.

We’re learning calculus, the secret of the universe.

Intention makes the little, big

One of Sam’s first speech therapists missed many scheduled home sessions. Early childhood programs usually begin in the home for toddlers who need services like Sam did. By the time I thought I should complain about her absences, however, Sam was “aging out” of the program. Once a child reaches 3 years old, education officials offer preschool along with speech and other services. Preschool offers a far richer environment to learn much more and much faster — as long as your child is ready to learn that way. Sam went to preschool where another speech therapist was assigned to work with him. She kept her schedule.

I’ve been thinking a lot about our family’s first autism experiences as Shahla and I put the finishing touches on our book. Given what could have been for our family 30 years ago, I feel really lucky.

It’s odd to call it lucky that Sam missed so many of his first speech therapy sessions. I didn’t consider it lucky back then. Sam had just been diagnosed. There was a lot of work to do. The therapist wasn’t doing her part of the work.

Yet, when she did keep her appointments, they were powerful. She took time to explain to me what she was doing as she worked with Sam. She wanted me to understand and keep things going when she wasn’t around. Since she missed so many of her appointments, I pivoted toward that goal pretty fast. (Honestly, I think she was battling depression.) I wasn’t a trained speech therapist. But I was soon thinking about Sam’s speech development all the time and responding to him in those thousand little moments you have every day with your child.

It took a while to see how lucky that was.

Sam was in primary school when I met Shahla. Shahla also helped with his progress, but that, too, took a while for me to see. There was still a lot of work to do and I was always trying to line up help. Shahla and I would chat occasionally about how things were going. I would share a story of some happening, often whatever was vexing us at the time and she would explain what was going on behind the curtain. Those little conversations were actually a deep dive for me. I understood better what was happening with Sam and where to go next — just as his wayward speech therapist was trying to show us.

We were learning to work smarter, not just harder, of course. But there was something else.

Sam couldn’t be forced or coerced — not that we wanted to work that way. Like many children with autism, in my opinion, the ways that he protected himself from the outside world were effective and strong. Still, we made progress. His best outcomes came after we approached things in a straightforward way with his full participation. The better we got at being deliberate, respectful, and intentional, the more momentum we created.

Even though Sam is a grown-ass man, we still seize the small moments to make a difference. I’ve been working at home for a while now, and that’s come with more opportunities for those small moments. With Mark gone and both Sam and I working full-time for the past decade, we didn’t have many. These days, we can chat over breakfast or lunch (or both) before Sam heads to work. Like every young adult, Sam sometimes turns his adult mind back to childhood experiences and tries to make sense of them. I’m glad to be here as he puzzles through all that. I’d like to think he’s puzzling through more because of these opportunities.

These days, he’s also been thinking a lot about why alarm bells bothered him so much when he was in elementary school. I told him he wasn’t alone, that no one likes that sound. That was a revelation to him, since apparently the rest of us hide that aversion so well. But he’s really wrestling with this, breaking things down into the science of sound, analyzing sound waves, and figuring how to manipulate them. He wants to make his own science to help others who hate alarm bells as much as he did. Who knows? Maybe he’s got something like Temple Grandin’s squeeze machine going in his sound lab back there, ready to banish those anxiety-making monsters once and for all.

Happy progress, indeed.

Community of practice

I finally moved my personal things out of my old office space, thanks to the help of a co-worker who also had to listen to me prattle on about things like how many piano makers there were before and after the Great Depression and why that might mean something to journalism now.

I have a century-old, upright grand piano. My parents got it for me when I was first learning to play. It has a big sound, especially after I had it rebuilt about ten years ago. The man who rebuilt it told me that before the Great Depression there were more than 400 piano makers in the United States. After the Great Depression, there were just two.

That seemed a stunning loss to me. Many people love music and enjoy playing, even if just for themselves. Pianos are among a handful of instruments that play both melody and harmony. However, our attention is never guaranteed, and our money usually follows wherever our attention goes.

That same drifting attention is happening to the news business now. Businesses needed your attention, so they got it by putting their advertisements next to news. Newspapers were among the original public-private partnerships. The better quality the news — a real public service at that point — the more valuable that space got. That is, until our attention started to drift.

One of the Denton newspaper’s most popular reports was the police blotter, at least before the pandemic began. It had long been a guilty pleasure for readers. Of course, now they can find even more guilty reading pleasures on Facebook, a company only too happy to hoover up the advertising revenue as people’s attention drifts over there. Probably in another year or two, there will be only a handful of news outlets left because the business model that extracted value out of our attention has changed so much.

Some people have finally figured that out, that the business model now is for people who recognize they need solid journalism to make sound business decisions and to make good public policy decisions.

Without that, we will soon have warlords squabbling for years while ticking time bombs sit in our harbors.

I’m ready to stop thinking about the business model and start thinking about the community of practice — journalists are a group of people concerned about the quality of information, how it’s gathered and vetted, and how to do it better, and the best way to do that is by debating all those values regularly among your peers — and then publishing or broadcasting.

This community of practice in journalism is also the same thing that people like to criticize as “the priesthood” or the “legacy elite” or “media bubble” or whatever other pejorative they want to hurl at the wall that might stick for the moment. But humans create communities of practice because they care about what they do and want to do it better, and scholars are beginning to recognize how much this phenomenon has helped all kinds of businesses do better and make progress in our modern world.

My first introduction to communities of practice came in the autism world, with parents sharing wisdom and such. Eventually, parents started seeing that the best therapists with the most powerful ideas kind of hung out together and fed off each other’s practice and research. No one was talking to you about a “community of practice,” but if you wanted the best for your child, you always wanted to be close to that, since chances were higher that your kid would benefit from all that supercharged brainpower and skill.

I encouraged Michael and Paige to find the equivalent as they ventured out into the working world, although I didn’t have the vocabulary for it at the time. At the University of Iowa, they organized the dorm into micro-communities that way and Paige fell right in. She’s still friends with many of her original writing community. Michael got a power introduction to the concept as a behavior tech in the autism world. He’s like a heat-seeking missile for that value where he works.

Journalists sometimes compete with each other, but we benefit from each other’s successes and critical takes on each other’s work. The successful business model(s) will depend on the rigor within our community of practice. As business models disappear and fail, that doesn’t mean the community of practice must also, but it makes it a lot harder. Until the emerging business models stabilize, our environment is ripe for propaganda disguised as news. But if our community of practice disappears, no business model will save it.

Just like the piano makers.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #322

Peggy: So, how did the haircut work out yesterday? Do you need me to trim the sides a little more?

Sam: Nah. There was one spot, but I cut it and I think it’s ok now.

Peggy: You did? That’s great that you could do that. (pause) I’m not a professional.

Sam: Well, I’m ten times worse than you.

Peggy (laughing): That’s haircutting in a pandemic.

Learning from the world around you

Young parents recognize when the kids start to absorb information from the world around them and (we hope) act accordingly. Kids are watching and listening and thinking and so you’ve got to take a little more care with the grown-up stuff.

We’ve got to let the rope out eventually, since the kids need to fly on their own. But we might not want to be the scary one with all that grown up stuff, because life’s pretty scary on its own.

The ability to absorb from the environment didn’t work the same way for Sam as it did for his brother and sister. As a child with autism, his attention could be hyper-focused or super-zoned out. When he was a toddler, we were never quite sure how much he absorbed from what was going on around him. But over the years, we coached and cued. We became more confident he was seeing what he needed to as he grew up and responded.

(For example, we worried at first that he didn’t understand traffic and would never watch for cars. Eventually, he proved he could and would learn to drive.)

I’m not sure what helped him recognize that important things he needs to know come in small, even sneaky ways. Over the past year or so, I’ve watched him notice small things going on around him far more than he used to. He’ll pick up the newspaper from the table and read a bit because the headline grabbed his attention. He might make a comment about the story over breakfast.

He’s learned when to ignore email and when not, which really a miraculous thing when you think about it. He still doesn’t like opening his snail mail (to be truthful, I don’t either, so what is with that?) but when he sees the envelopes that matter, he doesn’t truly ignore them. He knows what’s inside and opens them when it’s time to pay the bill or renew the tags, etc.

A few days ago, he saw a flier advertising a Social Security workshop in the pile of mail. He asked a lot of questions. He’s still healing from the stress of repaying a substantial amount of benefits last year. We knew when he got his full-time job at the warehouse that his benefits could finally end. We happily went down to the Social Security office and gave them notice, but it took months for them to stop sending checks. I cautioned Sam to sock that money away — they would eventually ask for it back. They did, and he was ready, but it was still really stressful for him.

He thought perhaps the flier came from Social Security and he needed to attend. I’m not sure if there’s a rule of thumb to help him wade through that type of information. I’ll think about it. But in the meantime, I told him, ‘nah, that flier was for me because I’m getting old.’

.

Dream Driving

Some dreams aren’t nightmares, but they leave you feeling unsettled in the morning. For me, the best remedy is to get them out of my head and move on. Recently, we discovered that works for Sam, too.

Like his mother, Sam is not really a morning person, although I’m not sure what a morning person is. We both feel fine when we’ve had enough sleep. However, we don’t feel like we’ve had enough sleep if we have to wake up before first light, even when we go to bed early.

Sam steps into the coffin that his supervisors would later race during Denton’s Day of the Dead festival.

Sam rarely talks about his dreams, unless they are nightmares. But he struggled and complained about that “morning funk” this fall, so a few weeks back, I asked him if he’d had a bad dream and what it was about.

He said it wasn’t really a bad dream, but he didn’t like it. He dreamt he was driving and that, in his dream, when it came time to stop, he somehow wasn’t able to move his foot from the gas pedal to the brake. He worried it could happen in real life.

I didn’t want to tell him it would never happen, because it’s important to tell the people you love the truth. And the truth is, just before a wreck, you are keenly aware how fast things are happening in front of you and how your car isn’t doing what you wish it would.

So I told him I had my own version of that dream, a recurring one. In my dream I am riding in the back seat of a car, careening somewhere fast, when I look up and realize that no one is driving. From the back seat, I struggle first to get my hands on the steering wheel, and then try to get up front to get to the pedals, but I never seem to make it.

Sam laughed and said my dream was really funny. I told him that the reason my dream was funny was because it was both relatable and ridiculous. I asked him if it made him think about his dream differently, and he said, yes, it made his dream kind of funny, too.

Then I asked whether he thought the dreams could be a metaphor for something.

And this is where I am so very, very grateful for Sally Fogarty and the other teachers who were on Sam’s special education team when he was in middle and high school. Sally announced at one of the annual planning meetings that Sam’s speech had come along enough that he would pass the usual tests meant to detect deficiencies. But, she added, we all knew that Sam’s language skills still needed work. She suggested that she administer another diagnostic test and develop a plan that would help him with more abstract language skills–analogies, idioms, metaphors and the like.

A few years later, Sam and I happened to be driving into Fort Worth and a billboard in Spanish caught our eyes. I read the billboard and understood the words, but I didn’t understand what the billboard was saying. I asked Sam, who was also studying Spanish, if he understood the billboard, because I couldn’t. And he said, “Well, that’s because it’s an idiom.” And then he told me what it meant. That was 15 years ago, and it still makes me tear up.

Sam agreed dream driving could just be the general way we feel about how our life is going, and maybe we don’t need to worry that we can’t always steer, and honestly, we don’t want to stop.

Racing alone

Another year of equestrian Special Olympics has come and gone. Sam had an off year this year, I think in part because the regional competition had to be canceled for bad weather. He and his teammates missed some of the momentum needed in competition.

Sam remained a sportsman through the disappointments. I almost thought he wasn’t feeling it – until it was time to head back home. He was sad to leave, saying that we always have fun but the competition wasn’t what he’d hoped for. Then he added that maybe next year he would only do drill.

Sam’s been branching out as a horseman this year. For many years, he only rode English. A few years ago, he added Western events. That opened the door to barrel racing, which is a barrel of fun. This year, he added carriage driving and drill.

Sam picked out the drill music first, which brings its own kind of joy for him. He and Mal, his riding coach and drill partner, did well on their short routine, especially considering how little time they had to practice. Since no one else had a routine with such challenging moves, they were competing against themselves at state Special O. They got gold.

I understood what Sam was saying. He wanted to race alone.

There’s a moving passage in architect Nader Khalili’s memoir, Racing Alone, where he explains his internal transformation, leaving a successful practice as a high-rise architect to develop prototypes for sustainable earth architecture.

Khalili tells the story of watching his son play with his friends. They have a foot race and his son, who is smaller than the other boys, falls behind and loses. Crying, the boy tells his father that he only wants to race alone. Khalili takes his son to a quiet track and watches him, full of joy, run and run.

Our children can be such magical teachers.

First Installment

Sam’s a bona fide taxpaying citizen now. It’s a funny thing to cheer, but cheer we do — because becoming a contributing member of society is the dream of every adult, right?

When Mark died almost 12 years ago, my sister, Karen, took me practically by the hand down to the Social Security office to apply for survivor benefits for the kids. Michael and Paige were both under age 18. And eventually, Sam collected, too, because Mark was supporting him when he died.

Michael and Paige’s benefits ended the summer after they graduated high school. Sam’s benefits continued for years because he never earned enough money until he started at WinCo two years ago.

We were faithful and went back to the Social Security office to tell them that Sam got a good job and would no longer need benefits. We expected them to stop sending checks much sooner than they did.

As the checks continued to arrive, I advised Sam to save as much as he could because eventually Social Security would ask for that money back. This was not our first rodeo. Back when the agency started Sam’s benefits (it took several extra months for his to begin), no one did the math against what was already coming our way for Michael and Paige. I had no idea there were maximums or what they were for our family. And when Social Security figured it out, we owed a lot from the overpayment. It hurt, but we paid it all back.

By the time Social Security figured out earlier this year when they should have stopped sending checks to Sam, the balance due was a stunning amount of money. Sam stresses about it sometimes, but we took this as a learning opportunity.

I helped him make a repayment plan and the whole concept of budgeting is sinking in. Sam has always done a good job with his finances, but it’s not hard to do a good job when you don’t really spend much money. This time, there’s some real pressure on his earnings, and he’s figuring it out. He’s gone several months now without the safety net. And, tonight he wrote a check for his first installment to repay the overpayment.

Yep, a bona fide taxpaying citizen.

Book report

Over the past ten days, I went back to read a book that had been recommended many times but I hadn’t until now: Clara Parks’ The Siege.

Her book is a parent memoir, but in a class by itself. If I had read her book when Sam was first diagnosed, many pages would have been dog-eared and worn for her wisdom. Parks was an English teacher at Williams College and had her master of fine arts degree. In other words, she knew the value of keeping a daily journal, and thinking critically about what was happening in her family, and applying what she knew about language — and how it was different for her daughter, Jessy (Elly in the book’s first edition) than her other, older children.

I was struck by how many experiences we had in common. Both Sam and Jessy proved their intelligence in unusual ways, which required their families to pay attention. They both kept elaborate maps in their head that allowed them to return to a place even if they’d only been there once.

Both Sam and Jessy also had distressing episodes with vomiting.

And I will digress at this moment to say that researchers have been far too slow to try to understand this problem. Many, many parents report their young children with autism have distressing digestive problems. Parks wrote about her daughter’s in 1967; it’s not like researchers can say they were surprised. Parks gave the problem enough ink that the skeptical reader knew her own theory about the mystery was just that. But, as far as I can tell, it wasn’t until Andrew Wakefield’s disgraceful paper in The Lancet that funders and scientists got serious about understanding digestive problems that children with autism have. Besides faking his numbers to gin up the vaccine connection, Wakefield went into that vacuum of knowledge about autism and digestive problems to give his idea that same sticky quality you find in urban legends.

A publisher once told me that he gets pitched a lot of parent memoirs. He doesn’t publish them any more. They don’t sell. That’s sad. It’s not that Parks’ memoir is the be-all-end-all (although I suspect that if I’d read her book as a young mother, I would have been too intimidated to write one of my own.) But I don’t think we’ve even begun to scratch the surface about what parents have observed, and what that might mean for furthering scientific understanding.

For example, Parks’ observations about language were stunning. Speech pathologists likely understand more about language development in children with autism than they did in 1967, but there’s just too much thoughtful description in her book for me to believe that they’ve got it all.

It’s true that it doesn’t have to be a memoir. Maybe there’s another way to capture all those stories and wisdom to make it better for the next generation of parents and children.

The Grand Tour

I missed the big day when the WinCo warehouse had its open house almost two years ago. Michael and Paige went with Sam, and got to see where Sam had trained as well as the spot where he works inside that massive building.

Sam will celebrate his second anniversary with the company in March. A few days ago, I took part of the day off to ride to work with him and finally get a tour of the place.

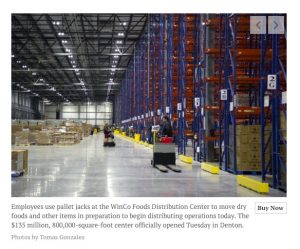

(Here’s a news story from the opening, shown in the Denton Record-Chronicle photo shown above.)

Sam’s unit unpacks small dry goods, such as shampoo and lotion, that are continuously delivered to the warehouse. They move them into bins that can be quickly accessed for shipment to stores in the region. (Sometimes he works on that repacking side, too.) They keep about 18,000 inventory bins stocked at all times. Much of the work is automated, which means he’s working with computers and all kinds of lifts and conveyors.

Once they’ve unpacked a delivery box, they throw the empty box up on a conveyor to the cardboard compactor, which was the highlight of the tour for my inner 8-year-old. The grown-up in me nearly melted watching his face light up showing me how it all worked. He is clearly enjoys his job, and is good at it — his supervisors told me as much, too.

When Sam first joined the workforce almost 15 years ago, a dear friend in the rehab department at the University of North Texas told me that Sam would learn and grow a lot on his first job. I was so grateful that he told me that, because I knew not to be surprised, and to be alert and responsive to those changes. I remember how challenged I felt entering the work force (a feeling that returns with each new job, and sometimes each new assignment, honestly), but I wouldn’t necessarily have connected to those experiences and been ready to help Sam in reinforcing his growth and understanding all of his new experiences, rather than being bewildered by them.

For example, I told him he might be surprised at how tired he would feel going from part-time to full-time work, especially such physically demanding full-time work. He was happy I shared that experience. After a few months, he was ready to advocate for himself in a powerful way: to get moved to swing shift. He knew he was not a morning person and that he needed more rest than he was able to get working day shift.

He also gained a lot more confidence in his strength. I don’t know what it is about autism, but it seems like lots of kids with autism don’t grow up with the core strength that most neuro-typical kids have. Horseback riding probably helped Sam get stronger than he was initially wired for.

But I knew WinCo put that over the top when I asked him to help me load a dryer on the back of my pickup, the kind of two-person job we had done many times over the years. I planned on taking the dryer to my girlfriend in Houston, who’d been all but wiped out by Hurricane Harvey’s flood waters. After I put down the tailgate and anchored the ramps, I turned around to see that Sam had already loaded the dryer on the dolly. He walked it all up the ramp without a word, like the grown-ass man he is.