Posts by Peggy

Vaccinating and the truth

Our extended family has been checking in with one another as we get vaccinated. We are scattered across several states, each with differing priorities and abilities to deliver the vaccine. Still, we cheer each other’s progress as we all approach the finish line.

Texas ignored essential and frontline workers in making its priorities, emphasizing shots for nursing home residents and seniors instead. Texas also got behind other states in getting shots in arms (color me not surprised). As fears rose with the fourth wave of new infections full of variants, I worried that Sam would get sick before Texas got around to vaccinating his age group.

For a while, our best hope seemed that our county was doing a good job in spite of it all. Both Dallas County (with millions of residents) and Denton County (with less than a million) have been holding mass vaccination events and both celebrated the 250,000 mark this week.

As soon as Denton County opened its vaccination list to all adults, I signed Sam up. He was at work when I did. I knew he wanted to take care of it himself, but I told him if we’d waited, even just those few hours for him to get home from work, who knows how many thousands would have gotten in line ahead of him?

The strategy seems to have worked. Sam’s appointment came the first day of the first week for the new cohort—all Texas adults. After he got his appointment, he took the unusual step of group texting his siblings and his aunties with the news. He got the high fives, but his brother and one of his aunties also reminded him that it was a shot and he would feel it.

He needed to talk about that. Sam has been accustomed to the extra steps the nurses at his regular doctor’s office take for inoculations, including applying a topical anesthesia to take the edge off. Knowing that wouldn’t happen at a mass vaccination event made him nervous. I reminded him that his brother and aunt were being very loving by telling him the truth about what to expect.

I did my best to continue the truth-telling by answering his other questions about what to expect since mass vaccinations are different. He asked me to drive him. He said he didn’t think he could manage his anxiety and drive, too. (He is not alone in that. I’ve volunteered at the speedway a few times and have seen plenty of folks shore each other up that way.)

When the moment came and the medical reserve volunteer opened the car door to administer the vaccine, he noticed Sam’s anxiety. We acknowledged it—it was the truth, after all—and he immediately shifted gears to help ease the way for Sam. The volunteer may not have had topical anesthesia, but his care had the same effect. Once inoculated, Sam said he was surprised how easy it was. The volunteer laughed and told him that applying the bandaid was the biggest part of the job. Then they both laughed.

I learned early on that it’s always better to tell Sam the truth. First of all, any child will stop trusting you if you say things like “shots don’t hurt” when you know perfectly well that they do. In addition, when Sam was little, he needed us to bridge him to the rest of the world. We couldn’t afford to be wiggly, amusement park rope bridges. Also, he doesn’t know what to do with white lies or half-truths. (Heck, they used to confuse me, too, but Sam also taught me that if you take people at their word instead of playing along, it’s their turn to be confused.)

Sam has his best shot at identifying and asking for what he needs when we tell the microscopic truth. Don’t we all?

I asked him whether he still wanted me to drive him for his second shot. Yes, please, he said.

Power outages and the power of plain language

Save the warnings by the National Weather Service, our household would not have been prepared for the freezing weather and massive power and water losses Texas suffered last week. From late Sunday night through Thursday afternoon, we endured rolling blackouts as two separate winter storms came through North Texas. Unlike many Texans, we didn’t lose our household plumbing in the cold, but our city’s system lost water pressure and we were without safe drinking water from Wednesday afternoon through Saturday morning. We also had no home internet service for most of the week.

As the meteorologists gave their forecasts, the conditions looked to me much worse than they did in 2011, the last time we had a day of rolling blackouts. Since that debacle, I’d read Ted Koppel’s book “Lights Out,” a sobering assessment of life after a catastrophic grid failure. Sam has friends who eventually gave up on living in Puerto Rico post-Maria. I recognized the incredible risk embedded in that forecast. We prepared like a hurricane was coming, with extra food, water (including filling the bathtub), and other provisions. We sheltered our plumbing as best we could.

If we had been waiting for cues from state or local public officials, we would not have prepared.

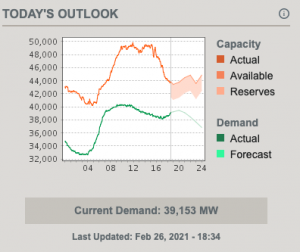

Once the crisis began, it was hard to explain to Sam what was happening. We had little official information to go on. For example, I couldn’t tell him when we might be able to depend on having power again, because no one was saying. I showed him the homepage for the state’s power grid, which has a good visual for what’s happening at the moment. On the outage days, there were bizarre spikes in future capacity, as if ERCOT expected four or five generation facilities to come back online at any moment.

Of course that wasn’t what happened. During the second day of rolling blackouts, we would get a phone call once or twice a day from the city utility, telling us to expect rolling blackouts for the day or night. But those calls said nothing about the grid status or when power would return.

After meteorologists called for warming on Saturday, we made contingency plans to get through to that day. I warned Sam that the power might be unreliable for days or weeks afterward. Power companies had rotated the power off in some places and couldn’t rotate it back on. That could mean the grid is damaged in places, I told him.

Also, when the blackouts started, I couldn’t tell him when the power would be on or off. There was no discernible pattern and we weren’t told. After about 24 hours, the city’s robocalls suggested a basic pattern, although we predicted it more closely using our oven clock as a reverse timer. We also observed street lighting changes as a predictor when we’d be shut off. If it was particularly quiet, Sam could hear the power coming back before the lights went back on. As a result, we could plan for things we needed to do to survive, like prepare food or charge our phones.

But that adaptive mode was ours to determine, and sometimes I had to coach Sam through it. Nothing was ever suggested to us by a public official how to cope with rolling outages, or how cold your home could get before it became too dangerous to sleep there, and the like.

When the city’s water system failed, our city made daily phone calls with recorded messages. They told us when the system was failing and how to help, then they told us when it failed, then they told us how recovery was going, and finally they told us when it was safe to drink again. That communication helped.

Sam does well with most of what adult life throws at him, but one of the few things he still struggles with is “official” communication.

Frankly, we all do better when public officials communicate with us in plain language. That is one reason why the federal government adopted the Plain Writing Act of 2010. I recognize the writing style when I get a letter from the IRS or the Social Security office. They always write in plain language so that even when your situation or the law around it is complicated, they use vocabulary and syntax you can understand so you can act accordingly.

For people with autism, such plain language communication is vital. Sam would likely have suffered greatly in last week’s outage without someone with him to translate what little information we were getting and work to fill in all the voids. ERCOT wrote arcane tweets about load-shedding, for example, and asked people not to run their washing machines. Still shaking my head about that.

We’re both still recovering from the trauma of last week. The trauma was made far, far worse by the lack of communication from state officials. As they set up their circular firing squads in Austin this week, we are learning that they knew this problem was coming and they knew it was a problem of their making. I’m sure individuals were panicking and that made it difficult to make good choices, but that’s why, in calmer moments, they are supposed to write and practice emergency plans. This was foreseeable and preventable. However, in my darkest moments, I sense that the lack of communication was a choice, one they made in part to avoid blame.

This week, I’ve also been stunned by how many people stung by this abject failure expect it to happen again. They simply do not expect our state to be able to fix this mess.

I want to reject that premise, but, mercy me, if it happens again, can they at least have the decency to communicate to us, and in Plain Language?

Overheard in the Wolfe House #325

Peggy (after listening to an automated message lifting the boil water notice): Sam! The tap water is safe again! We can do whatever we want with it.

Sam: Except waste it.

Pandemic and the after times

Hopefully, this week tips the balance between the number of people Sam and I know who got sick with COVID-19 (a lot) and the number who’ve been immunized (only a handful). Texas has lagged the rest of the country in delivering vaccine, and our county has lagged even further, at least until they organized this week’s 10K-per-day, multi-day, drive-through shot clinic at the speedway.

The pandemic forced Sam and me to reshape our lives quite a bit over the past year, and the routine that evolved likely helped our mental health. We took a few days at Christmas to visit Michael and Holly in Austin (combining our bubbles proved just fine) and found that, in coming back home, re-establishing the daily rhythm took a little effort. We thought our routine was a gentle one, but it was a routine nonetheless.

Now, we can see that the routine will change again as the pandemic recedes. Sam says he finds it hard to imagine that things will go back to the way they were, even though he would like to go dancing again and some horseback riding competitions could return. Those leisure activities mean taking time off work, something he’s done very little of in the past year.

In addition, we like much of what we’ve folded into our lives since the pandemic shut us in. We found time to learn calculus, which has become a small, joyful part of nearly every day now. We also look forward to bike riding on the weekend. (We signed up for a virtual challenge because, first, his sister suggested it, and second, because it seemed like a peak pandemic-y thing to do.) And Saturday night has become movie night for us in a way that Alamo Drafthouse couldn’t replicate, snacks and all: we set the schedule and we curate our own themes. Right now, we are watching films that explore civil rights and our country’s dark history of white supremacy.

Many new things we do may continue, including the favorite parts of our routine. Sam says he will continue wearing masks for allergy season or whenever he needs to protect himself from dust. I suspect we may don them in public other times, too. It’s kind of gobsmacking how, in the before times, we were expected to go to work with a cold, or otherwise be out and about and infecting each other. Egad.

In other words, I don’t think it’s just the family dog who’d rather we keep the current routine. Maybe that old routine from the before times wasn’t so free after all, subjecting us all to much more of a rigid and unhealthy grind than we remember.

Take it to all four corners

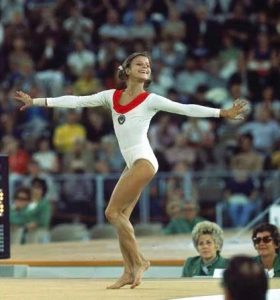

Olga Korbut changed the face of gymnastics when I was in junior high school. She looked so graceful and athletic in Seventeen magazine’s photos from her performance at the 1972 Olympics. As you might imagine, many of the wiggly tweens in my gym class were excited that our teacher added a gymnastics unit, largely because of what Korbut had inspired. Now, we could all experiment with moving through the world that way. That’s also when I learned one of the rules of floor exercise: a gymnastics routine can borrow from dance and mix in lots of tumbling, but it must also go to all four corners of the mat.

It’s a curious rule, yet wise when you think about it. It requires the competitor to be thorough as they challenge their body. I started thinking about that rule again recently and decided to add it to my ongoing pursuit of small, yet large, New Year’s resolutions. For 2021, I plan to take things to all four corners.

Last year’s resolution, Wear An Apron, feels prescient now, given the pandemic. We certainly spent a lot more time in the kitchen in 2020. But the bigger idea behind it–that whatever problem we faced, someone out there solved it already–kept us grounded, too. Online, we found Khan Academy to help Sam (and me) learn calculus as well as a sewing pattern and instructions for face masks vetted by some pragmatic nurses in Iowa. On YouTube, I started following a smart yoga instructor and my dad’s favorite backyard gardener, a fellow in England whose bona fides begin with his unapologetically dirty hands. Even streaming The Repair Shop revealed wide-ranging wisdom about problems I didn’t even know could be solved. Awesome.

Thinking ahead to this year, I remembered an editor who would remind us reporters to nail down all four corners of an investigative story before publication. Smart advice, but it also created a defensive image in my mind’s eye rather than something inspired by filling up the space of a gymnastics mat. Don’t get me wrong, it’s important to be able to rigorously defend your choices and actions, but the big idea for 2021 shouldn’t be about the pursuit of perfection. Instead, going to all four corners means planning thoroughly, and being careful and deliberate.

Raising kids, especially someone like Sam who needed so much, shunts the pursuit of perfection to the side in favor of steps that move toward progress. But I can’t say we always took it to all four corners.

For example, Sam does pretty well in the kitchen. All my children learned cooking and cleaning basics and food safety. Now, Sam does so well with some recipes that I can plan time off in the kitchen when he steps up. But I know we haven’t taken it to all four corners. Managing a kitchen is hard with all the planning and shopping. And the principles of cooking that let you tackle a new recipe, that’s something else, too.

So, not such a small idea after all. But it may be warranted for 2021, because I bet once we let loose the reins from the pandemic, there could be many things that need to be thought through again, and to all four corners.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #324

Sam (inputting complicated equation for calculus lesson): Oh, poor Mathway!

Peggy: What?

Sam: It had to do a line break.

Lessons of calculus

Sam didn’t learn calculus in high school and has decided, now that he’s in his 30s, that this deficit in his education must be remedied – not just for him, but for me, too.

I was a bit of a math whiz in junior high and high school, and while I didn’t get much calculus instruction either, I was somehow destined to review algebra, geometry, and trig lessons at least once a decade as the kids grew up and as Sam struggled with advanced algebra classes in junior college. To share in Sam’s enthusiasm for this new endeavor, I picked up Steven Strogatz’s book, Infinite Powers. It’s a persuasive little tome about the secrets of the universe and the author has nearly convinced me that God speaks in calculus. (And, perhaps that is why we have a hard time understanding Him.)

Sam doesn’t need all that. He just wants to master the principles and formulas (Hello, Kahn Academy) to break free of the limits he feels in his amateur music and sound studio, acquiring the demigod ability to manipulate the sound waves his computer produces.

Sam and I have been chipping away at this calculus thing for several weeks, beginning with a thorough review of the fundamentals. We know you can’t do the fancy moves until you’ve got the basic blocking and tackling down cold.

Through this journey, I’ve watched Sam learn a lot when we make mistakes. Kahn Academy tutorials ring a little bell and throw confetti every time you get an answer right. We don’t stop and think about how we nailed it. However, get the answer wrong and we are motivated to go back to find the missteps. Somehow, examining that failure locks in the learning just a little deeper.

Some writers and thinkers dismiss the fandom that failure gets in the business community. (Failing Forward! How to Fail like a Boss!) They are right: platitudes can’t turn failing into big money and success. That whole ready-shoot-aim philosophy just gets you muscle memory for ready-shoot-aim, in my experience. Examining your choices and, importantly, your knowledge deficits before making changes is what gets you back on the path of progress.

When I was in graduate school at the Eastman School of Music, some of us sat for a short, informative lecture from brain researchers at the Strong Memorial Hospital (both the school and the hospital are part of the University of Rochester). They showed us how the brain looks for motor patterns in the things that we do (walking, for example) and then files those patterns with the brain stem once established. It makes our learning and doing more efficient. But, of course, for practicing musicians, that tendency is a terrifying prospect. Practice a music passage wrong often enough and your non-judgmental brain says, “Aha! Pattern!” and files it away for safekeeping. The last thing you want is for that incorrect pattern to trot itself out when you are stressing. That’s how mistakes happen in a big performance. And they do. All. The. Time.

Sam and I are doing our best to go slowly and learn how to work the principles and formulas right the first time, or at least going back to retrace our steps when we trip up so we walk it through correctly on the second pass.

We’re learning calculus, the secret of the universe.

The man, the mail-in ballot, and meaning

Sam signed up for mail-in ballots after the pandemic began. Texas allows individuals with disabilities and voters age 65 and older to vote by mail.

He registered as a Republican after learning that he would miss at least one upcoming local election if he didn’t. Turns out, he got two test runs with the mail-in-ballot routine before the big one — the November presidential — arrived. In mid-July, Denton County had a run-off between two GOP nominees for state judge in the 431st District Court. Then we unexpectedly had a crowded race of Republicans and a lone Democrat vying to succeed our former State Senator, who let no grass get under his ultra-ambitious feet as he hopscotched his way from newbie Texas resident and the state legislature into Congress this year.

When the November ballot arrived in the mail in early October, Sam opened up the envelope and spread its contents across the dining room table. He grabbed a pen and colored in the box to vote for president. He took a deep breath, saying that it felt powerful to vote for Joe Biden. He stood up and announced then that he would come back to finish the rest of the ballot later.

The ballot was long. It included federal, state, and county offices. It also included city offices, as the Texas governor postponed local races because of the pandemic. When Sam returned to finish voting, he surprised me how prepared he was to make informed choices all the way down.

He’d been watching our current president, and deteriorating conditions for a long time. He had thought long and hard about how to vote for change.

Our current president proved himself irredeemable to us when he mocked a reporter with a disability in 2015. The past four years have been so bad that it was genuinely shocking — and should not have been — to watch Joe Biden return the affection of a man with Down syndrome who rushed to hug him several years ago.

It’s a hard thing to explain to people who haven’t been on this journey, what it is like to regularly experience another human being’s black-heartedness in a deeply personal way. When Sam was little, we shielded him. Now that he’s an adult, we have to talk about it.

Those are the worst conversations. Not because Sam gets hurt, or because we don’t have strategies for him, but because we parents are hard-wired to protect our children. When I hear these stories, or watch things unfold in front of me, I want to slap somebody. I haven’t so far, so I guess the strategies are working for me, too.

Sam told me about a week before Election Day that he was going to want to watch the returns on election night, in hopes that his choice would prevail with everyone else. Election night was tough, but as the days went by, you could see the tension lift. Sam is not just relieved, but happy.

“I voted for Joe Biden as hard as I could,” he said.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #323

Peggy: The Mayborn Conference is announcing a new contest, a short story in six words. Writers have been trying to do those kinds of short stories long before Twitter. I have a story like that. It kind of went viral on Twitter. It has more than 170,000 views.

Sam (laughing): Really? That’s great.

Peggy: So here’s the story. “Midnight. Wrong train platform. Shinjuku station.”

Sam (still laughing): That’s just a mishmash of words.

Intention makes the little, big

One of Sam’s first speech therapists missed many scheduled home sessions. Early childhood programs usually begin in the home for toddlers who need services like Sam did. By the time I thought I should complain about her absences, however, Sam was “aging out” of the program. Once a child reaches 3 years old, education officials offer preschool along with speech and other services. Preschool offers a far richer environment to learn much more and much faster — as long as your child is ready to learn that way. Sam went to preschool where another speech therapist was assigned to work with him. She kept her schedule.

I’ve been thinking a lot about our family’s first autism experiences as Shahla and I put the finishing touches on our book. Given what could have been for our family 30 years ago, I feel really lucky.

It’s odd to call it lucky that Sam missed so many of his first speech therapy sessions. I didn’t consider it lucky back then. Sam had just been diagnosed. There was a lot of work to do. The therapist wasn’t doing her part of the work.

Yet, when she did keep her appointments, they were powerful. She took time to explain to me what she was doing as she worked with Sam. She wanted me to understand and keep things going when she wasn’t around. Since she missed so many of her appointments, I pivoted toward that goal pretty fast. (Honestly, I think she was battling depression.) I wasn’t a trained speech therapist. But I was soon thinking about Sam’s speech development all the time and responding to him in those thousand little moments you have every day with your child.

It took a while to see how lucky that was.

Sam was in primary school when I met Shahla. Shahla also helped with his progress, but that, too, took a while for me to see. There was still a lot of work to do and I was always trying to line up help. Shahla and I would chat occasionally about how things were going. I would share a story of some happening, often whatever was vexing us at the time and she would explain what was going on behind the curtain. Those little conversations were actually a deep dive for me. I understood better what was happening with Sam and where to go next — just as his wayward speech therapist was trying to show us.

We were learning to work smarter, not just harder, of course. But there was something else.

Sam couldn’t be forced or coerced — not that we wanted to work that way. Like many children with autism, in my opinion, the ways that he protected himself from the outside world were effective and strong. Still, we made progress. His best outcomes came after we approached things in a straightforward way with his full participation. The better we got at being deliberate, respectful, and intentional, the more momentum we created.

Even though Sam is a grown-ass man, we still seize the small moments to make a difference. I’ve been working at home for a while now, and that’s come with more opportunities for those small moments. With Mark gone and both Sam and I working full-time for the past decade, we didn’t have many. These days, we can chat over breakfast or lunch (or both) before Sam heads to work. Like every young adult, Sam sometimes turns his adult mind back to childhood experiences and tries to make sense of them. I’m glad to be here as he puzzles through all that. I’d like to think he’s puzzling through more because of these opportunities.

These days, he’s also been thinking a lot about why alarm bells bothered him so much when he was in elementary school. I told him he wasn’t alone, that no one likes that sound. That was a revelation to him, since apparently the rest of us hide that aversion so well. But he’s really wrestling with this, breaking things down into the science of sound, analyzing sound waves, and figuring how to manipulate them. He wants to make his own science to help others who hate alarm bells as much as he did. Who knows? Maybe he’s got something like Temple Grandin’s squeeze machine going in his sound lab back there, ready to banish those anxiety-making monsters once and for all.

Happy progress, indeed.