Like the old days

Last week, Sam competed in the Chisholm Challenge, which has been part of the Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo for 18 years, (and Sam has competed every year.) The entire event was canceled last year, so simply returning to the arena felt like a victory. Plus, Sam got bucked off in practice last week, so getting back on the horse was a victory, too. Although, to be honest, I don’t think he would have considered any other option. Here are three short videos from speed events.

Ranch Riding. Sam came in first place.

Barrel Racing. Sam’s time came in second place.

Pole Bending. Sam’s time came in fourth place.

Prepared. Resilient.

I had forgotten how wonderful a warm fire feels on a cold day. We had a wood stove at the farm. After we moved to town, installing a wood-burning fireplace insert went on the to-do list, but it would always slip down a few notches as other things crept up the list.

I grew up in Wisconsin. I have never been so cold in my life. We saw the forecast, so we prepared. We filled three five-gallon jugs and the bathtubs with water. We had two weeks’ worth of food (although my plans to make lasagna mid-week were foiled). I also made a point of finishing the laundry on Sunday night.

Back in 2011 the power outage didn’t last as long, but we didn’t suffer because the wood stove kept us warm and heated coffee (always essential) and food. Here in town we have a gas furnace, but every time the electricity rolled off during Uri, so did the heat. Getting a wood stove went to the top of the to-do list.

As the good people at Heffley’s installed the fireplace insert this fall, I learned how lucky we were that we didn’t chance using the old gas logs. (Before we moved in, the home inspector declined to check the fireplace. He told me to get a plumber instead. That job never even made the to-do list.) We discovered that the rock façade had separated from the chimney. We probably would have set the house on fire that week.

The whole experience made me re-think what it means to be prepared and resilient. We took care of some of that this year. But buying stuff (we also got a Goal Zero battery with solar panels and a portable cooktop) doesn’t necessarily make you prepared and resilient.

Perhaps the last five years’ of resolutions were leading to this moment — saying no to buying stuff, saying yes to new experiences, better connecting to others, wearing an apron (looking for simple solutions), and taking it (whatever it might be) to all four corners.

Sometimes I think about those worst-case scenario books the kids loved when they were young. They were often funny and terribly fantastical (dodging an alligator attack or elephant stampede, landing a jet, etc.) but after Hurricane Harvey, I wondered how to pitch the tent on the roof. In the meantime, we will set up our go-bags.

Climate change is here. Time to be prepared and resilient.

Reagan was wrong. There is no trust when you must verify.

The first time I took Sam to school and left him for a full day was a big leap of faith. I wasn’t alone, of course. Parents want to protect their kids. And parenting a child with autism or other disability puts that protective feeling into overdrive. Eventually I saw that we weren’t alone. His many teachers and therapists were part of his village. Later that year, I walked into a special education team meeting and recognized that, for the first time in Sam’s young life, I was not “on call” for every minute of every day. It was such a nice feeling, one that left room for more thinking and reflecting about our lives, and for resting, too.

That’s not to say that his school years were perfect. We knew not everyone in his life would be as mindful. But we also knew that the perfect is the enemy of the good. When conditions warranted, someone at school picked up the phone and told us about an emerging problem. We addressed many small things before they got big. And we learned to celebrate the average and the good enough, which was its own kind of achievement for Mark and me.

So (and you knew there was a so, didn’t you, dear internet people?), I struggle deeply with the burgeoning installment of security cameras at school. We aren’t just pointing cameras at the school’s exterior doors. Or in the hallways. Or from the school resource officer’s body armor. We are pointing them inside the classrooms, too.

In Texas, parents can ask for a camera in their child’s special education classroom. The school must get consent from parents of the other kids in the class, but such camera use is on the rise. Advocates for kids with disabilities continue to press the legislature for broadening a family’s rights to footage. One day, some parent will send their child with a disability to school with a body camera if they believe it’s necessary.

I recognize that school can be a rough place for children who don’t fit in for one arbitrary reason or another. Sam was getting hassled in the boys’ bathroom one year, and solving the problem proved tricky for the aides, both women. But we figured it out.

I recognize also that some schools are hard pressed to fill their teaching ranks. There are employees without enough skills to work with and manage kids, the place where most tragedies begin.

This is not to say that people in our community might have different values from my family’s or yours. As a culture, we wobble too much in figuring out how to work with those differences as strengths and educate our children. But I have to say, where parents are asking for cameras, we aren’t reading those huge warning flags.

When Sam graduated high school, I wanted everyone from elementary school on up to have a “Team Sam” button as a little token of our esteem and affection. I ordered 250 buttons and did not come close to gifting all those people who touched his life and helped him make progress. Dozens of teachers, of course, but also speech therapists who worked with him on communication skills. Occupational therapists and adaptive physical education teachers who helped him with his motor planning and ability to calm himself. School counselors who helped him build friendships. Aides who helped him stay on task in class and occasionally take a moment to decompress when he couldn’t. And the principals and other staff who stood by and made sure all those people had the support they needed.

I had to trust these people. All of them. A lot.

There was no “trust but verify.” Where there are cameras, there is no trust.

Never been to Spain, finally made it to Maine

Sam and I were supposed to go to Spain last year. We booked a cycling tour with the same outfitter that took us to Italy and Germany, and Paige and me to Ireland, over the past several years. We booked before the pandemic, but even as the lockdown began, we were thinking, naively, that with a little luck, the virus would be under control by summer, when the cycling tour would take us through the countryside around Cordoba, and into Seville and the Alhambra. Ha. Spain was being ravaged by the virus by then, and our country was on the verge of its own, first big wave. About six weeks out, the outfitter canceled the trip and refunded our money.

Sam and I biked around town last summer. It was very quiet.

When the tour catalog came for summer 2021, it seemed unrealistic to make any kind of plan to go abroad. Even the handful of U.S. tours they had, though they looked to be as much fun, felt risky. But we had to have a little faith. Our world had gotten really small. I wondered if we didn’t try to make something special happen, our mental health would suffer even more than it was. The vaccine roll-out had begun. Maybe a fall tour to see the leaves in New England could be a safe bet. Surely, the virus would be subsiding by then. Ha ha.

The company’s tours to cycle in Vermont filled up fast, so we missed that. They offered a self-guided tour of Acadia that we’d heard was good. We booked for the first week of October.

Ever since the vaccine rollout, Sam has been pushing back on letting our lives get too busy again. He wants more “thinking time” for math and signal projects he’s working on. He likes the quiet pace we found, and I agree it’s a treasure to keep. While traveling to Maine was a little discombobulating (we were really rusty with the whole packing-parking-screening thing), once we got there, it was exhilarating–as you can see below, with the boys checking the view from the Bar Harbor shoreline our first night in town:

We cycled all through Acadia National Park, learned about lobstering (and ate a lot of it), watched the stars, and got out on boat rides several times. During one nature cruise, our guide, a retired park ranger, asked how many of us would have gone abroad this year but came to Maine instead. About half of the 50 people on that boat raised their hands. Even the guide was a little surprised. Later, we visited about that moment with one of the wait staff at a brew pub who also worked part-time at the local visitors bureau. She said that they, too, had noticed many more people requesting information this year. Good for Maine.

Sam’s favorite part of the trip was that nature cruise, which took us by some of the favorite hangouts for seals, porpoises, and sea birds, including two huge osprey nests. We also saw some stunning homes along the shore. My favorite part of the trip was cycling the carriage roads through the park. They were so quiet.

The Silver Linings Playbook

The world will break your heart ten ways to Sunday. That’s guaranteed. I can’t begin to explain that. Or the craziness inside myself and everyone else. But guess what? Sunday’s my favorite day again. I think of what everyone did for me, and I feel like a very lucky guy. — The Silver Linings Playbook

Sam and I were invited to the wedding of some old friends last weekend. The couple had postponed their celebration because of the pandemic, but like most of us looking for a little bit of normal, they, too, saw the covid vaccine as a way through to their special day. We said yes to some beautiful normal that day, although we still weren’t quite feeling fully normal. We masked up for the ceremony and stayed out on the patio for the fun. It was the best day.

Sam hasn’t been able to go dancing–one of his favorite things–much at all for the past year and half. He joined an Eastern swing dance club several years ago, but they closed with the first covid lockdown last year and opened for a club dance only once, as far as Sam can tell, just before the surge of the delta variant put a damper on everything again. I think the only time he’s been out is when his aunties took him dancing on a mountain biking trip in June. (Remember June, when we thought we were finally free of it?)

On the way to the wedding, I told him there would be a DJ and music and a chance to dance. He said he wasn’t sure about staying at the party that long, let alone dancing. “It’s risky, Mom,” he said.

But, as you can see in the photo above, his eyes were soon on the dance floor. He waited for a bit, hoping a the DJ would spin a good swing dance number, but after a few tunes, he decided he would just make his move. He danced quite a bit, including at least one number with the bride. He’s a lucky guy that way.

Small, little men

The national media is noting the ignorance and cruelty in Texas public policy, including the new laws that ban abortion and suppress voting rights. I would argue that the state’s policies and governance vis-à-vis people with disabilities amply demonstrates that this ignorance and cruelty isn’t new.

Elected officials in Texas have refused for years to adequately fund the medical and disability services that allow individuals to live in the community and avoid costly (especially to taxpayers) institutional care. Federal programs can pay the lion’s share of these services, and in most other states they do, but Texas refuses to expand Medicaid enough to allow that to happen. Instead, they authorize puny levels of funding for “waiver” programs—part of the federal law that allows Texas and other states to opt out with the promise to take care of people in their own way. But really what Texas does is pretend the burden doesn’t exist. Instead of fostering human progress, Texas disability policies hardwire families and communities for long-term suffering.

Sam was in kindergarten when we first moved to Texas. We followed the advice of the good people at Denton MHMR and put his name on one of the infamous waiting lists for the state’s waiver programs. Our social worker said that even though we couldn’t be sure then what services Sam might need when he was 18, we’d have no chance at help if he wasn’t on a waiting list. At the time, we were among the young families that got a little help paying for respite care and for special equipment, so we picked the waiting list for the waiver program most like that.

(Sadly, a year or two later, even that modest state program for young families ended. We were on our own.)

Families who are able to access services under these sparsely funded waiver programs understand them much better than I do. Sam made enough progress and adapted well enough that he doesn’t need the help—the kind of basic human need that tends to make allies and advocates into battle-hardened experts in the shortcomings of public policy.

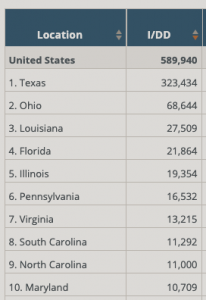

But I do know that the Texas waiting lists for waiver programs are cruelly long. Nationwide, there are about 600,000 people on a waiting list and more than half of them are on a list in Texas. (For context, remember that less than 9 percent of the nation’s population lives in Texas.)

In its latest budget, the Texas Legislature funded additional slots to get more people into the waiver programs, but not nearly enough. Some advocates and self-advocates have done the math: the Texas list is so long that individuals could wait their whole lives and never receive services.

When other states would get in this deep, they agreed to Medicaid expansion made possible by the Affordable Care Act. Waiting lists for waiver programs in those states nearly disappeared because Medicaid expansion stepped in to fund those services.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Texas is among just 12 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. Texas is, by far, the most populous state to refuse to provide services at a meaningful level and make no real progress toward that goal.

Some advocates wonder whether the U.S. Department of Justice will intervene, especially when U.S. Department of Health and Human Services officials seemed to wobble on approving the state’s waiver program earlier this year. It’s a great question, but we need look no further than the state’s troubled institutions—called state supported living centers—to see how a negotiated settlement might go. Independent federal monitors have visited those centers since 2009, after fresh reports of abuse and neglect emerged with cellphone video of a “fight club” forced on residents at the Corpus Christi center. All 13 centers were supposed to meet negotiated standards by 2014 or face further action, up to and including closure. Twelve years later, none of the centers (home to about 4,000 people with developmental disabilities) met the standards, the monitors still make regular visits, and all 13 centers remain open at increasingly unsustainable costs to state taxpayers.

Texas is growing fast and its people need a far more robust physical and social infrastructure than state officials seem to grasp. Some people see our governor moving about in a wheelchair and think he’s got the disability thing covered. But advocates know better. “He’s not one of us,” I heard one self-advocate say recently, pointing out the many, many differences between an individual who must adapt their entire life when compared to the governor’s experience, where the need for a wheelchair came much later in a life of privilege.

These days, Texans are watching their governor and the other small, little men in state leadership race to the bottom in a panic to maintain power. In that twisted race, their lawmaking and policies are displaying new levels of ignorance and cruelty for all to see. But color me not surprised, as the ignorance and cruelty has been part of their law- and policymaking for our community for a very long time.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #327

Peggy (to Sam, after sharing news with cousins about second co-authored book on its way): You wrote a chapter for my first book, remember?

Sam (to cousins): Yeah, Mom can’t write a book by herself.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #326

Sam (after sitting down briefly in the easy chair, rises and returns to kitchen): That pizza’s gotta cook. I’m hungry.

Conservative guardianship

Britney Spears’s battle to be free of the conservatorship that has governed her affairs touches familiar themes for us old-timers in the disability world. She’s asking for the grown-up version of the least-restrictive environment, the federal right of children with disabilities to receive a free, public education alongside their peers in regular education classes, with support, if necessary.

For now, the least-restrictive environment is the best way we know to ensure every child has access to all they need to learn and grow into their best selves.

Over the years, I’ve seen a few families struggle to understand what guardianship really means. Adults need a least-restrictive environment, too. When Sam approached high school graduation, we were told that, as his parents, that we’d better think about setting up guardianship before he turned 18. It has been a few years now, and perhaps understanding has improved among the teams that do this transition planning, but at the time, Mark and I really thought that recommendation came out of left field. We’d fought for Sam his whole life for him to be included at school and in the community, to be in that least restrictive environment. Something about guardianship felt very restrictive to us.

Then an older, wiser friend boiled it down for us. “You’ll have to tell a judge, in front of Sam, that he’s incompetent.” I can still see Mark’s face when he realized what that meant. “We could never do that to Sam,” he’d said. To which I’d replied, “oh, hell no, we couldn’t.”

I often bring the salt, just FYI.

For our family, that ended the guardianship discussion right there. I did poke around a little, however, to figure out ways we could be his bumper guard. Once you start looking around, there are all kinds of ways to be there for someone, even in a somewhat official capacity, from bank signatories to putting both names on a vehicle title to advance directives and more–all without ever stepping foot in a probate court.

Last week, I learned even more about the power of supported decision making, an alternative to guardianship that gets you in the door when your loved one really needs you. These documents are legally recognized, even if your loved one is ensnared in the criminal justice system. One-page profiles can also help a lot for those times you can’t get in the door–when your loved one is in the hospital with covid, for example.

When your loved one truly needs a guardian, it pays to be thoughtful and as minimally restrictive as possible. That can be tough in Texas, just another FYI.

This year, advocates helped defeat a troubling bill filed in the Texas House of Representatives during the last regular session. If it had passed, the bill made it too easy for parents to get and retain guardianship of their teen. The legislation was inspired by one family’s tragedy, but it was rife with unintended consequences that would have stripped many young adults of their autonomy—especially if special education transition teams in Texas school districts are still advising parents to pursue guardianship without thinking it through.

Refrigerator Mother 2.0

Only a few generations ago, some doctors blamed mothers for their children’s autism. Psychologists wrote long theoretical papers based on their observations of mothers and their children. They concluded that autism mothers were cold and that their lack of love triggered the child’s autism.

If you stop to think about that idea for a minute, those explanations were quite a leap. And a cruel one at that.

We humans look for patterns in the world around us–it’s almost one of our super-powers. We use the information to make meaning, and create loops of ferocious thinking that make the world around us a little better.

Therefore, knowing that we’re supposed to make things better, the Refrigerator Mother explanation for autism just begs the question. How much did those early theoreticians consider and—most importantly, rule out—before concluding they’d observed a pattern of mothers who don’t love their children?

Granted, many people were immediately skeptical of these mother-blaming theories, including other professionals and autism families. The theories fell after a generation, but the damage was done to the families forced to live under that cloud as they raised their children.

And, the blame game is still out there.

The latest iteration has started in a similar way, with people seeing problematic patterns in autism treatment. Young adults with autism are finding their way in the world. Some of them had good support growing up, but the world isn’t ready for them. Some of them had inadequate support growing up, so they have an added burden as they make their way in a world that isn’t ready for them either. Some are speaking up not just about the world’s unreadiness but also about that burden. We must listen. Autistic voices can help us find new patterns and new meaning and build a better world for all of us.

We should be careful about letting one person’s experience and voice serve as the representation for the whole, because that’s how the blame game begins. Even back in the old days, when information was scarce, we had the memoirs of Temple Grandin, Sean Barron, and Donna Williams to show us how different the experiences can be. As Dr. Stephen Shore once said, if you’ve met one person with autism, then you’ve met one person with autism.

Here’s an example of how that can break down: some now argue that asking an autistic child to make eye contact, as a part of treatment service, is inherently abusive because eye contact feels bad for them. Missing from that argument is the basic context, the understanding that for humans to survive, we need to connect to one another. For most of us, eye contact is the fundamental way we begin to connect, from the very first time we hold and look at our new baby and our baby looks back at us.

I asked Sam recently (and for the first time) whether making eye contact is hard or painful for him. I told him I was especially curious now that eye contact changed for all of us after living behind face masks for a year. He said this, “Eye contact is very powerful. I wonder whether I make other people uncomfortable with eye contact.”

He’s right. It is powerful. And he just illustrated the point about one person’s perspective.

When Sam was young, we never forced him to look at us. But after a speech therapist suggested using sign language to boost his early communication, I found the sign for “pay attention” often helped us connect.

The additional movement of hands to face usually sparked him to turn his head or approach me or Mark in some way, so we were fairly sure we had his attention and that was enough to proceed with whatever was next. Over the years, we’ve shared eye contact in lots of conversations and tasks. But if not, we recognized the other ways that we were connecting and I didn’t worry about it.

All of this context—both the need to survive and the difficulty with a basic skill needed for that survival—cannot go missing from any conversation about the value of teaching an autistic child. Some people with autism do learn how to make eye contact early on and are fine with it. Some don’t. For this example, then, we can listen carefully to adults with autism and their advocates as they flag patterns from their bad experiences with learning to make eye contact and make changes. But that fundamental need to connect and share attention remains.

That’s when we also need to remember our tendency to blame others when our troubles feel intractable. Sometimes, in these fresh arguments over how autism treatment should proceed, I hear that same, tired pattern of blame I’ve heard since Sam was born. Take it from a worn-out mother who’s been blamed plenty over the years: some arguments are just another round of the same, they just come inside an elaborate wrapper of mother’s-helper blaming instead.

All the families I know truly love their children and are learning how best to respond to them. We can’t forget that parents have a responsibility to raise their child as best they can. Let’s talk, please. But please also, let’s spare the rollout of Refrigerator Mother 2.0, because it could cost us a generation of progress.