Posts by Peggy

See Sam Drive, EV edition

We had to get up early today to meet the man delivering Sam’s new car. He bought a 2018 Chevy Bolt from the Fort Collins, Colo., dealer where my brother-in-law works. Sam was so very patient. When his uncle mentioned they had two Bolts on the lot waiting for their recall work, Sam put $500 down. That was back in December 2021.

Sam has been driving a 2001 Toyota Corolla since he first learned to drive 15 years ago. He also bought that car from his Uncle Matt. We started talking about replacing the Corolla around 2018-19, but Sam moves slowly with these kinds of decisions. He went to the auto show at the State Fair with his brother and sat in a Chevy Bolt. He tentatively decided he would replace his car in 2020. Then the pandemic came and life slowed down so much. It bought him a lot more time to shop for a car, which was good, because Chevy needed time, too, to make those battery repairs.

He didn’t need much coaching through all of this, at least not from me. Matt may have had to work a little harder to make the sale and delivery, I certainly can’t speak for him. The only thing I really weighed in on was getting the car back to Texas. We talked about flying up to get the car and driving back, but once we crunched the numbers, shipping won out. He agreed to do it, since it was cheaper by about a factor of 10.

He still has a bit of a to-do list — insurance, Texas plates, toll tag, etc. I did write that up and put it on the fridge for him, so I suppose that’s coaching. And he’s going to reach out to other EV drivers for wisdom, since this car is several generations more sophisticated than either of the vehicles we currently drive.

Life really is so flipping complicated. I have little idea how I got through things the first time myself, although I do remember a habit in my 20s of calling my parents often and asking adulting questions. I do also prompt my other kids–probably more than they would like–with the preface of ‘let me tell you something I learned the hard way and save you some time/money/heartache.”

Have you ever thought about all the problems you solved in your 20s?

A rose behind a geofence is just a rose, fenced

The word geofence joined the English language in the mid-1990s. As I type the word “geofence”, Microsoft Word doesn’t correct my spelling—yet, chances are high that if I want to talk with Sam about geofencing, the first thing we would have to do is talk about the word’s definition in plain language.

Sam inspired me to become a plain language fan. It’s not just because we now have the Plain Writing Act of 2010, a federal law that sets the standards for certain government agencies to better communicate with people.

When talking with Sam in plain language, we usually find some great truths. We have to be thinking very clearly to boil stuff down to its essence. And then Sam, always a great thinker, figures out what that essence means and where that new essence belongs in his life.

So, the word “geofence” in plain language: A boundary line on your computer.

We sometimes say that good fences make good neighbors. The poet Robert Frost had more to say about that. In other words, a fence on a computer has meaning, too.

Our local transit agency, DCTA, experimented with a computer fence to offer van rides to the west side of town a few years ago. Sam used that van service to get to work a few times. It was very hard. I rode with him once. First, you had to travel to the fence line, then you could hail the van that only gave you rides inside the fence lines.

The day I went with him, I had to wait a half-hour to ride back to the other side of the fence. While waiting, I saw dozens of DCTA vans driving Peterbilt workers to destinations that I knew were traveling far beyond the fence lines I was traveling in.

Recently, our transit agency has drawn new fence lines for van rides. At first glance, the big pasture of service seems generous. But at the same time, they also cut most of the buses whose lines weren’t fences, but veins.

Suddenly, yet predictably, too many riders are coming from certain areas. DCTA says they may “geofence to manage demand.”

Or, in plain language: they will draw lines that push riders out.

Sam has told me more than once that he wants to ride bus to work. I began to doubt whether that would ever happen after I saw the long line of Peterbilt-subsidized DCTA vanpools. Then, when an apartment developer paid extra for DCTA to run a bus to its massive apartment complex adjacent to the warehouse district (beyond even the millions UNT pays DCTA to run buses), I gave up hope. We don’t, and probably won’t ever, have a system to serve the thousands of people like Sam, who can make their lives better with the mobility that connects them to economic opportunities–let alone the magical world that exists for all of us when our community has that kind of mobility.

Some politicians (and their constituents, of course) will always be attracted to lines like geofencing. Playground games follow the boundary lines. Winners and losers are determined by the lines. And, as we all know, some kids aren’t allowed inside the boundaries to play at all.

I doubt our transit agency board recognizes the deepest meaning of its actions as it draws these lines. The longer they allow those fence lines to exist on computers, the more those lines become real-life walls.

Mixing and mingling

Shahla and I had a book signing a week ago. Donna Fielder, a wildly successful Denton author, encouraged me to talk to the owners of the newest book store in town, Patchouli Joe’s, to see whether they were interested in hosting an event for us like they did for her. It took a while for me to screw up the courage, but once I did, they were as gracious as Donna described.

Shahla and I didn’t know quite what to expect, but we prepared for the gamut, from doing a formal reading before a crowd of strangers to sitting quietly in the hopes that at least one or two book buyers stopped by. Turned out, many friends and family came and we had a different kind of crowd. Suddenly, a formal reading didn’t seem right, so I asked if anyone had questions. We were off and running. After about an hour, we were getting tired, so Shahla deftly ended the Q&A. A few people lined up to get books signed, but most lingered, browsing the shelves and chatting with each other.

Shahla and I answer questions about our new book at Patchouli Joe’s in Denton. Photo by Annette Fuller.

Up until then, Sam had been sitting behind us in a comfy wing chair. When he recognized that it was mix-and-mingle time, he popped up from the chair and started walking around the store, introducing himself and chatting with people. I couldn’t help but smile. That afternoon, Sam was doing much better than I was in being a social butterfly.

Here’s why. Years ago, he joined a local dance club. He learned Eastern swing dance steps, met lots of new friends, and waited patiently for women to ask him to dance. He was out in the community in this highly social way at least once, usually twice, a month. As the pandemic has waned, the dance club is slowly rebooting and he’s been out dancing again. He’s enjoying the return of social sparkles.

When Sam was little and learning to imitate and to talk, I thought we were going to have to break down all kinds of skills into incremental steps in order for him to learn. But once he learned to talk and to imitate, that elevated his ability to “learn to learn.” Suddenly, we didn’t have to break things down anymore. I never fully understood that phenomenon until Shahla explained behavioral cusps: once a person masters a skill or environment, that often leads to picking up other kinds of skills and expanding opportunities. Sam absorbed a variety of social skills while learning to dance.

Not everyone is the same. For example, I’m not sure that joining a dance club would boost my introverted ways. But, finding and achieving a cusp is something powerful to think about when you feel stuck. We touch on this concept several times in the book. Working toward a behavioral cusp can help us achieve progress and sustainability in our parenting. We all learn this way our whole lives–it’s one of humanity’s super powers.

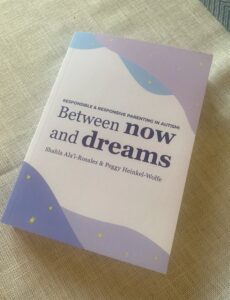

P.S. Where to buy our new book, Responsible and Responsive Parenting in Autism: Between Now and Dreams

See Sam Drive, Horse and Cart Edition

Sam started driving lessons about two years ago. Sam would watch other riders at Born 2 Be dress up in costumes and drive their carts in exhibition drills that he enjoyed watching. I mentioned he didn’t have to resign himself to watching, he could participate and he finally decided to give it a try.

Today wasn’t his first competition, but it was the first time I was able to go and get video for you, dear internet readers. We got to the stables (near Terrell) about 9 this morning, in time for Sam to watch his instructor and many of the other competitors. His class was the last of the day to compete, and he was the last competitor. (You will see that he is joined in the cart by his instructor as a safety measure. Also, we very grateful that it was all done by noon. We both napped after we got home. It’s going to be a long and very hot summer this year.)

He said that he planned to trot the “Fault and Out” course. He’d seen a few people scratch over the course of the morning, but he was confident in his ability, along with Doc’s, to weave the cones. You can hear the whistle after the sixth set. In the stands, we were all surprised to hear the whistle because it looked like they were through, but Sam knew. He had to stop because he and Doc had knocked a tennis ball off the top of the cone. That’s the Fault. So they were Out.

Things went better for the Gambler’s Choice obstacle course. I learned that this, too, is a timed event, unlike trail patterns for riders. The more times he and Doc completed one of the obstacles, the more points they got. You will see that Sam started to try to back Doc and the cart into the U and bump out the back, but when things slowed down too much, he wisely gave up. I learned later that it’s quite difficult for a horse to back a four-wheel cart without jackknifing it.

After the events were over, one of the technical judges came by to encourage Sam and tell him what all went right. Sam told her he just wanted to finish the course anyways, because it was fun.

Racing alone. That’s the spirit.

Look for the Paul Hollywood handshake

For the first time in three years (thanks, pandemic), equestrians gathered for the statewide Special Olympics in Bryan last weekend. Sometimes, it felt like we hadn’t missed a beat (showmanship classes rolled like clockwork Sunday morning even though we were tired from the dance the night before) and other times, the grief over the lost time hit hard (hello, friend I haven’t hugged in five years).

I have to tip my hat at the organizers that recognized the athletes would benefit from an icebreaker after all these years. They outfitted each athlete with four of the same pins for their region. They had to meet riders from all the other regions in order to exchange pins and collect a full set: North, South, East, West.

It was fun to watch Sam and all the other athletes not only reach out to one another, but help one another complete their sets. God bless those who came all the way from out west to Bryan, which is in south central Texas.

Sam competed in five events in all. Many athletes in his classes are like Sam and have been riding for years. They are skilled and consistent riders. Some have their own horses. Some compete in able-bodied shows. Every once in while, though, it’s just Zen and the Art of Horsemanship and as it unfolds in front of you, it’s pure joy. I’ve posted video from all five of his events, but it was Working Trail where I wondered whether the roof would open and sun rays would shine down on Sam and Madrid, like in the movies. It was magical.

There are two moments you’ll want to savor. First, when Sam and Madrid are at the gate and you can see he knows how tell Madrid to sidle in closer so that he can easily remove and re-attach the rope. Then, the judge stands up, says “wow” and comes over to shake Sam’s hand.

A photo from the awards ceremony, courtesy of Yolanda Taylor, parent of one of the other athletes in this event:

Ways to buy Responsible and Responsive Parenting: Between Now and Dreams + Bonus Materials

Ways to buy the book

- Order paperback from Different Roads to Learning

- Order ebook from Different Roads to Learning

- Order paperback on Amazon

- Order Kindle version on Amazon

- Or, buy an autographed copy from Patchouli Joe’s in Denton

- Audiobook coming soon!

**Click here for bonus materials for parents, clinicians and the media**

Overheard in the Wolfe House #329

Sam (getting in the car): Get in the back, Fang.

Peggy: He’s gotta give you a kiss first.

Sam: That’s the thing with love. Sometimes you can’t escape it.

Reciprocity

Hello, dear internet people! Are you ready for another excerpt from the new book? In Part Two: The Power of Connecting in Between Now and Dreams (pre-order here!), Shahla and I describe what it means for parents to connect to others as they nurture their children. When we connect to one another, we foster our shared growth and we strengthen the beautiful ways we can respond to our child. All kinds of people bring energy and wisdom to this journey — friends, family members, neighbors, professionals.

We were particularly inspired by the woman who cut Sam’s hair when he was in elementary and middle school. Connie taught us all a great lesson about reciprocity in relationships.

Edited excerpt below:

Reciprocity, the ways in which we demonstrate our care for one another and influence and depend on one another, breathes life and depth into our relationships. Mutual dependence is part of the human experience. The most meaningful relationships might start by attending the same class, then remembering birthdays or taking turns buying lunch, eventually deepening over the years by sharing child care or stepping in when someone starts cancer treatment. Reciprocal interactions with family and friends not only nourish our lives but can also help our autistic child by creating healthy and natural dependencies that bring progress in a sustainable way. When we understand and value reciprocity, we can boost its practice and our family’s quality of life.

Consider how young children learn to play together, for example. A child without autism approaches another child at preschool who is playing with cars, but just by watching the action at first. Then, the child picks up another car and begins playing along. After a minute or so, the two children create together an imaginary scenario for the cars. The play then becomes a learning, rewarding experience for both of them. That is one key of reciprocity—it is founded on mutual reinforcement. Each person receives some benefit in the relationship. The benefit may be transactional, meaning that something immediate happens that both parties value. The benefit can also be relational, meaning that things happen over time that are important to both individuals, and the value occurs when they are together. Reciprocity also involves coordinated and shared attention. Each person finds happiness in the other person’s happiness.

Many of us, including our children with autism, struggle with reciprocity, especially in the beginning. We are all in the process of learning about reciprocity in our own growth and development. Consider the circles of people around us who make our life better and help further our understanding. For most of us, family and close friends make up the inner circle. Groups of friends from spiritual communities, social clubs, or sporting activities are in the middle. The outer circle is filled with our acquaintances and professionals, such as our barber, school counselor, or family doctor.

Michael Ball, an elementary school guidance counselor in Texas, thought a lot about the friendship circles among the schoolchildren. The students with disabilities, he knew, would have a hard time developing friends for their inner circle from that middle circle of friendships. To change that environment, he created many circles of friends, inviting a student with a disability into his classroom once a week along with several children without a disability to spend time together. He offered the circle of friends an activity they would all enjoy. He was careful to pick something the child with a disability could do with some success, yet something all the children would enjoy doing or playing. Then, he’d let things unfold, working with them to solve problems along the way, if needed.

Children with autism often need coaching or other guided practice to take part in basic reciprocal social interactions, such as playing with siblings at home, with friends on the playground, or at a birthday party. Other children with autism may only need priming or a special script that details what happens and how best to respond to basic social cues. Some children may also need to expand their interests so they have more to share and can find common ground with family and friends.

We can be on the lookout for interactions, large and small, that take advantage of the power of reciprocity to build our child’s world. Our child’s ability to move through these moments brings its own kind of mastery. That’s one reason that therapists work hard to teach very young children with autism how to imitate other people. Once our child can imitate others in different ways and situations, they are better equipped to learn many more things and faster. Their ability to learn and master new things can become so powerful that some structured teaching becomes obsolete for them, and reciprocity fills the gap. Reciprocity gives us access to new relationships. It’s like the difference for all of us after we learned to read—then we read to learn. We enjoy reading, too. We access new worlds when we read.

These big moments don’t stop in childhood. In their paper on behavioral cusps and person-centered interventions, Garnett Smith and colleagues described Sarah, who was twenty-two. Sarah’s grandparents were concerned that she was a homebody. She enjoyed watching college basketball on television. Her grandparents took a chance and encouraged a friend to take Sarah to a game. She enjoyed herself so much that she continued attending games and other large events. Her reciprocal interactions with other people increased exponentially. She talked with workers at the concession stand and with the players after the game. She participated in halftime activities. Her world expanded. In fact, Sarah developed a whole new set of social skills around the experience, a classic example of a behavioral cusp. She was much less of a homebody. She even asked her grandparents to go to other sporting events.

We can be on the lookout, then, for activities that capture reciprocal contingencies. Our child can join other family members preparing the table for a meal. They can take turns playing a board game with a sibling. They can write thank-you notes. In this way, everyone can be our child’s ally. Life is filled with many gentle back-and-forth interactions, all worth fostering because they make life better and have the potential to create their own sustaining energy for our child’s progress.

For example, Peggy’s son, Sam, couldn’t tolerate haircuts when he was a toddler. Peggy resorted to cutting his hair while he slept. It worked well enough, but when her next-door neighbor, Judy, a stylist, heard how they were coping, she offered to help. Judy brought her supplies to the house. Sam sat in the high chair in front of a full-length mirror in the living room. Sam told Judy how to hold his hair as she cut it. She was patient and went along with his directions, and still managed to cut it well.

When the family moved, Peggy wondered whether she would have to find someone willing to make house calls, like Judy did. She found another stylist. Connie had a big heart and boundless sense of humor. She kept Sam looking good from boyhood trims through the high school trends.

The whole family got their haircuts on the same day. Connie would ask Sam’s advice, who was next in the chair, and everyone conferred on the plans. As he got older, Sam stopped telling Connie how to hold his hair and let her cut it as she would for any client. Then, the conversation became whatever Sam or Connie wanted to talk about. Getting haircuts became a powerful lesson in reciprocity. Judy opened the door, and Connie showed how reciprocity builds those connections. She understood that the circle of what is given and received grows wider with the years.

Then Connie got cancer. Sam understood that she became too weak to stand all day and cut people’s hair. He found another barber. The relationships, begun by the simple act of cutting Sam’s hair, had brought out the best in everyone. When Connie died a year later, Sam and the rest of the family felt the loss of a friend. They still miss her.

Joy

Joy gives us wings! ― Abdul-Baha

Review copies of the new book I co-wrote with Shahla arrived on Saturday. It’s such a pretty little thing. All that warmth and wisdom on the cover is on the inside, too. And so is some really smart science. The release date is April 2. You can pre-order here.

A while back, the publisher shared an excerpt on their blog. I’ve included it below, editor’s note and all. It’s from Part Three: The Power of Loving. And it’s called Joy.

Editor’s note: Autism Awareness month is becoming a call to action from the autism and neurodivergent communities for change from the rest of society. In this edited excerpt from their upcoming book with Different Roads, co-authors Shahla Ala’i-Rosales and Peggy Heinkel-Wolfe offer a specific call to action to both parents and professionals—to seek and maintain joy’s radiating energy in our relationships with our children.

Parents have the responsibility of raising their children with autism the best they can. This journey is part of how we all develop as humans—nurturing children in ways that honor their humanity and invite full, rich lives. Ala’i-Rosales and Heinkel-Wolfe’s upcoming book offers a roadmap for a joyful and sustainable parenting journey. The heart of this journey relies on learning, connecting, and loving. Each power informs the other and each amplifies the other. And each power is essential for meaningful and courageous parenting.

Ala’i-Rosales is a researcher, clinician, and associate professor of applied behavior analysis at the University of North Texas. Heinkel-Wolfe is a journalist and parent of an adult son with autism.

“Up, up and awaaay!” all three family members said at once, laughing. A young boy’s mother bent over and pulled her toddler close to her feet, tucking her hands under his arms and around his torso. She looked up toward her husband and the camera, broke into a grin, and turned back to look at her son. “Ready?” she said, smiling eagerly. The boy looked up at her, saying “Up . . .” Then he, too, looked up at the camera toward his father before looking back up at his mother to say his version of “away.” She squealed with satisfaction at his words and his gaze, swinging him back and forth under the protection of her long legs and out into the space of the family kitchen. The little boy had the lopsided grin kids often get when they are proud of something they did and know everyone else is, too. The father cheered from behind the camera. As his mother set him back on the floor to start another round, the little boy clapped his hands. This was a fun game.

One might think that the important thing about this moment was the boy’s talking (it was), or him engaging in shared attention with both his mom and dad (it was), or his mom learning when to help him with prompts and how to fade and let him fly on his own (it was), or his parents learning how to break up activities so they will be reinforcing and encourage happy progress (it was) or his parents taking video clips so that they could analyze them to see how they could do things better (it was) or that his family was in such a sweet and collaborative relationship with his intervention team that they wanted to share their progress (it was). Each one of those things is important and together, synergistically, they achieved the ultimate importance: they were happy together.

Shahla has seen many short, joyful home videos from the families she’s worked with over the years. On first viewing, these happy moments look almost magical. And they are, but that joyful magic comes with planning and purpose. Parents and professionals can learn how to approach relationships with their autistic child with intention. Children should, and can, make happy progress across all the places they live, learn, and play–home, school, and clinic. It is often helpful for families and professionals to make short videos of such moments and interactions across places. Back in the clinic or at home, they watch the clips together to talk about what the videos show and discuss what they mean and how the information can give direction. Joyful moments go by fast. Video clips can help us observe all the little things that are happening so we can find ways to expand the moments and the joy.

Let’s imagine another moment. A father and his preschooler are roughhousing on the floor with an oversized pillow. The father raises the pillow high above his head and says “Pop!” To the boy’s laughter and delight, his father drops the pillow on top of him and gently wiggles it as the little boy rolls from side to side. After a few rounds, father raises the pillow and looks at his son expectantly. The boy looks up at his father to say “Pop!” Down comes the wiggly pillow. They continue the game until the father gets a little winded. After all, it is a big pillow. He sits back on his knees for a moment, breathing heavily, but smiling and laughing. He asks his son if he is getting tired. But the boy rolls back over to look up at his dad again, still smiling and points to the pillow with eyebrows raised. Father recovers his energy as quickly as he can. The son has learned new sounds, and the father has learned a game that has motivated his child and how to time the learning. They are both having fun.

The father learned that this game not only encourages his child’s vocal speech but it was also one of the first times his child persisted to keep their interaction going. Their time together was becoming emotionally valuable. The father was learning how to arrange happy activities so that the two of them could move together in harmony. He learned the principles of responding to him with help from the team. He knew how to approach his son with kindness and how to encourage his son’s approach to him and how to keep that momentum going. He understood the importance of his son’s assent in whatever activity they did together. He also recognized his son’s agency—his ability to act independently and make his own choices freely—as well as his own agency as they learned to move together in the world.

In creating the game of pillow pop, parent and child found their own dance. Each moved with their own tune in time and space, and their tunes came together in harmony. When joy guides our choices, each person can be themselves, be together with others, and make progress. We can recognize that individuals have different reinforcers in a joint activity and that there is the potential to also develop and share reinforcers in these joint activities. And with strengthening bonds, this might simply come to mean enjoying being in each other’s company.

In another composite example, we consider a mother gently approaching her toddler with a sock puppet. The little boy is sitting on his knees on top of a bed, looking out the window, and flicking his fingers in his peripheral vision. The mother is oblivious to all of that, the boy is two years old and, although the movements are a little different, he’s doing what toddlers do. She begins to sing a children’s song that incorporates different animal sounds, sounds she discovered that her son loves to explore. After a moment, he joins her in making the animal sounds in the song. Then, he turns toward her and gently places his hands on her face. She’s singing for him. He reciprocates with his gaze and his caress, both actions full of appreciation and tenderness.

Family members might dream of the activities that they will enjoy together with their children as they learn and grow. Mothers and fathers and siblings may not have imagined singing sock puppets, playing pillow pop, or organizing kitchen swing games. But these examples here show the possibilities when we open up to one another and enjoy each other’s company. Our joy in our child and our family helps us rethink what is easy, what is hard, and what is progress.

All children can learn about the way into joyful relationships and, with grace, the dance continues as they grow up. This dance of human relationships is one that we all compose, first among members of our family, and then our schoolmates and, finally, out in the community. Shahla will always remember a film from the Anne Sullivan School in in Peru. The team knew they could help a young autistic boy at their school, but he would have to learn to ride the city bus across town by himself, including making several transfers along the way. The team worked out a training program for the boy to learn the way on the city buses, but the training program didn’t formally include anyone in the community at large. Still, the drivers and other passengers got to know the boy, this newest traveling member of their community, and they prompted him through the transfers from time to time. Through that shared dance, they amplified the community’s caring relationships.

When joy is present, we recognize the caring approach of others toward us and the need for kindness in our own approach toward others. We recognize the mutual assent within our togetherness, and the agency each of us enjoys in that togetherness. Joy isn’t a material good, but an energy found in curiosity, truth, affection, and insight. Once we recognize the radiating energy that joy brings, we will notice when it is missing and seek it out. Joy occupies those spaces where we are present and looking for the good. Like hope and love, joy is sacred.

When there is so much hate and so much resistance to truth and justice, joy is itself is an act of resistance. ― Nicolas O’Rourke

Overheard in the Wolfe House #328

Peggy (watching Sam dismantle a stuck exterior door latch): Sam I think you could be a good burglar.

Sam: I’m working from inside the house.