language

Talk to yourself, and tap the ‘wisdom of the inner crowd’

Some years ago, I took a call at my desk in the newsroom from a woman with a news tip. The details of the tip escape me now, but her explanation stayed. She wanted us to understand why she was calling, because the situation suggested she’d been living a lie and she was making big changes. She told me that she had a growing interior life and she asked, didn’t we all? Yet her husband could not grasp the concept.

Although she made no reference to Christianity when we talked, this concept of an interior life has roots there. The idea is to have an ongoing conversation with God. By focusing on a friendly, internal exchange with your Creator, you can transform your actions into good works. The faithful call it “prayer.”

If you think about that for a minute, the word prayer can provide a powerful cover to these internal dialogues, especially when spoken aloud. (As does reading and writing, for that matter.) We need that cover because society tends to scorn (or worse) people who talk to themselves.

Now, science has discovered that it may be objectively helpful to talk to yourself. In the Wolfe house, we’ve tolerated thinking out loud. Over the years, we’ve learned to tolerate a range of human behaviors that we didn’t understand at first. Autism has often revealed our ignorance of behavior that is actually beneficial. So, we made room for the possibility that having conversations with yourself could be beneficial. To be sure, these internal-but-out-loud dialogues occur out of earshot of each other, although I still tend to direct my commentary to the dog, as long as I’m not confusing him.

The idea is that there could be wisdom in your “inner crowd.” There’s plenty of research into the wisdom of actual crowds. That research shows that when compiling diverse and independent opinions, they tend to average out, minimizing mistakes and revealing the truth. So, it doesn’t quite make sense that talking to yourself is going to expand your knowledge or change the internal biases that lead to mistakes.

However, some recent studies found that people can get closer to a good answer when they take another’s perspective. Researchers asked participants a factual question (such as the size or count of a thing), asking first for their own answer and then for an answer of someone who would disagree with them. In another study, researchers had participants outfitted for a virtual reality experience, one that contained an avatar of themselves and another Freud-looking avatar. The researchers prompted the participants to voice both avatars in a problem-solving conversation. They discovered that people were able to give themselves good advice.

The outcome reminded me of the power of social stories when Sam was a kid. The stories spelled out the social cues he otherwise missed. He always knew what the “answer” was. In other words, this idea may not be grounded in the principle of crowd-sourcing information at all. I think the idea is to create space. Talk out loud and you give yourself room to think and for all that inner wisdom to break through.

Here’s a couple resources to get you started talking to yourself:

Alter, Adam. (2023) Anatomy of a Breakthrough: How to Get Unstuck When it Matters Most. New York: Simon and Schuster.

https://behavioralscientist.org/tap-into-the-wisdom-of-your-inner-crowd/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9984468/pdf/41598_2023_Article_30599.pdf

A rose behind a geofence is just a rose, fenced

The word geofence joined the English language in the mid-1990s. As I type the word “geofence”, Microsoft Word doesn’t correct my spelling—yet, chances are high that if I want to talk with Sam about geofencing, the first thing we would have to do is talk about the word’s definition in plain language.

Sam inspired me to become a plain language fan. It’s not just because we now have the Plain Writing Act of 2010, a federal law that sets the standards for certain government agencies to better communicate with people.

When talking with Sam in plain language, we usually find some great truths. We have to be thinking very clearly to boil stuff down to its essence. And then Sam, always a great thinker, figures out what that essence means and where that new essence belongs in his life.

So, the word “geofence” in plain language: A boundary line on your computer.

We sometimes say that good fences make good neighbors. The poet Robert Frost had more to say about that. In other words, a fence on a computer has meaning, too.

Our local transit agency, DCTA, experimented with a computer fence to offer van rides to the west side of town a few years ago. Sam used that van service to get to work a few times. It was very hard. I rode with him once. First, you had to travel to the fence line, then you could hail the van that only gave you rides inside the fence lines.

The day I went with him, I had to wait a half-hour to ride back to the other side of the fence. While waiting, I saw dozens of DCTA vans driving Peterbilt workers to destinations that I knew were traveling far beyond the fence lines I was traveling in.

Recently, our transit agency has drawn new fence lines for van rides. At first glance, the big pasture of service seems generous. But at the same time, they also cut most of the buses whose lines weren’t fences, but veins.

Suddenly, yet predictably, too many riders are coming from certain areas. DCTA says they may “geofence to manage demand.”

Or, in plain language: they will draw lines that push riders out.

Sam has told me more than once that he wants to ride bus to work. I began to doubt whether that would ever happen after I saw the long line of Peterbilt-subsidized DCTA vanpools. Then, when an apartment developer paid extra for DCTA to run a bus to its massive apartment complex adjacent to the warehouse district (beyond even the millions UNT pays DCTA to run buses), I gave up hope. We don’t, and probably won’t ever, have a system to serve the thousands of people like Sam, who can make their lives better with the mobility that connects them to economic opportunities–let alone the magical world that exists for all of us when our community has that kind of mobility.

Some politicians (and their constituents, of course) will always be attracted to lines like geofencing. Playground games follow the boundary lines. Winners and losers are determined by the lines. And, as we all know, some kids aren’t allowed inside the boundaries to play at all.

I doubt our transit agency board recognizes the deepest meaning of its actions as it draws these lines. The longer they allow those fence lines to exist on computers, the more those lines become real-life walls.

Power outages and the power of plain language

Save the warnings by the National Weather Service, our household would not have been prepared for the freezing weather and massive power and water losses Texas suffered last week. From late Sunday night through Thursday afternoon, we endured rolling blackouts as two separate winter storms came through North Texas. Unlike many Texans, we didn’t lose our household plumbing in the cold, but our city’s system lost water pressure and we were without safe drinking water from Wednesday afternoon through Saturday morning. We also had no home internet service for most of the week.

As the meteorologists gave their forecasts, the conditions looked to me much worse than they did in 2011, the last time we had a day of rolling blackouts. Since that debacle, I’d read Ted Koppel’s book “Lights Out,” a sobering assessment of life after a catastrophic grid failure. Sam has friends who eventually gave up on living in Puerto Rico post-Maria. I recognized the incredible risk embedded in that forecast. We prepared like a hurricane was coming, with extra food, water (including filling the bathtub), and other provisions. We sheltered our plumbing as best we could.

If we had been waiting for cues from state or local public officials, we would not have prepared.

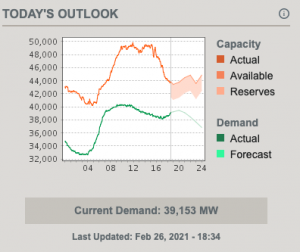

Once the crisis began, it was hard to explain to Sam what was happening. We had little official information to go on. For example, I couldn’t tell him when we might be able to depend on having power again, because no one was saying. I showed him the homepage for the state’s power grid, which has a good visual for what’s happening at the moment. On the outage days, there were bizarre spikes in future capacity, as if ERCOT expected four or five generation facilities to come back online at any moment.

Of course that wasn’t what happened. During the second day of rolling blackouts, we would get a phone call once or twice a day from the city utility, telling us to expect rolling blackouts for the day or night. But those calls said nothing about the grid status or when power would return.

After meteorologists called for warming on Saturday, we made contingency plans to get through to that day. I warned Sam that the power might be unreliable for days or weeks afterward. Power companies had rotated the power off in some places and couldn’t rotate it back on. That could mean the grid is damaged in places, I told him.

Also, when the blackouts started, I couldn’t tell him when the power would be on or off. There was no discernible pattern and we weren’t told. After about 24 hours, the city’s robocalls suggested a basic pattern, although we predicted it more closely using our oven clock as a reverse timer. We also observed street lighting changes as a predictor when we’d be shut off. If it was particularly quiet, Sam could hear the power coming back before the lights went back on. As a result, we could plan for things we needed to do to survive, like prepare food or charge our phones.

But that adaptive mode was ours to determine, and sometimes I had to coach Sam through it. Nothing was ever suggested to us by a public official how to cope with rolling outages, or how cold your home could get before it became too dangerous to sleep there, and the like.

When the city’s water system failed, our city made daily phone calls with recorded messages. They told us when the system was failing and how to help, then they told us when it failed, then they told us how recovery was going, and finally they told us when it was safe to drink again. That communication helped.

Sam does well with most of what adult life throws at him, but one of the few things he still struggles with is “official” communication.

Frankly, we all do better when public officials communicate with us in plain language. That is one reason why the federal government adopted the Plain Writing Act of 2010. I recognize the writing style when I get a letter from the IRS or the Social Security office. They always write in plain language so that even when your situation or the law around it is complicated, they use vocabulary and syntax you can understand so you can act accordingly.

For people with autism, such plain language communication is vital. Sam would likely have suffered greatly in last week’s outage without someone with him to translate what little information we were getting and work to fill in all the voids. ERCOT wrote arcane tweets about load-shedding, for example, and asked people not to run their washing machines. Still shaking my head about that.

We’re both still recovering from the trauma of last week. The trauma was made far, far worse by the lack of communication from state officials. As they set up their circular firing squads in Austin this week, we are learning that they knew this problem was coming and they knew it was a problem of their making. I’m sure individuals were panicking and that made it difficult to make good choices, but that’s why, in calmer moments, they are supposed to write and practice emergency plans. This was foreseeable and preventable. However, in my darkest moments, I sense that the lack of communication was a choice, one they made in part to avoid blame.

This week, I’ve also been stunned by how many people stung by this abject failure expect it to happen again. They simply do not expect our state to be able to fix this mess.

I want to reject that premise, but, mercy me, if it happens again, can they at least have the decency to communicate to us, and in Plain Language?

Overheard in the Wolfe House #323

Peggy: The Mayborn Conference is announcing a new contest, a short story in six words. Writers have been trying to do those kinds of short stories long before Twitter. I have a story like that. It kind of went viral on Twitter. It has more than 170,000 views.

Sam (laughing): Really? That’s great.

Peggy: So here’s the story. “Midnight. Wrong train platform. Shinjuku station.”

Sam (still laughing): That’s just a mishmash of words.

Dream Driving

Some dreams aren’t nightmares, but they leave you feeling unsettled in the morning. For me, the best remedy is to get them out of my head and move on. Recently, we discovered that works for Sam, too.

Like his mother, Sam is not really a morning person, although I’m not sure what a morning person is. We both feel fine when we’ve had enough sleep. However, we don’t feel like we’ve had enough sleep if we have to wake up before first light, even when we go to bed early.

Sam steps into the coffin that his supervisors would later race during Denton’s Day of the Dead festival.

Sam rarely talks about his dreams, unless they are nightmares. But he struggled and complained about that “morning funk” this fall, so a few weeks back, I asked him if he’d had a bad dream and what it was about.

He said it wasn’t really a bad dream, but he didn’t like it. He dreamt he was driving and that, in his dream, when it came time to stop, he somehow wasn’t able to move his foot from the gas pedal to the brake. He worried it could happen in real life.

I didn’t want to tell him it would never happen, because it’s important to tell the people you love the truth. And the truth is, just before a wreck, you are keenly aware how fast things are happening in front of you and how your car isn’t doing what you wish it would.

So I told him I had my own version of that dream, a recurring one. In my dream I am riding in the back seat of a car, careening somewhere fast, when I look up and realize that no one is driving. From the back seat, I struggle first to get my hands on the steering wheel, and then try to get up front to get to the pedals, but I never seem to make it.

Sam laughed and said my dream was really funny. I told him that the reason my dream was funny was because it was both relatable and ridiculous. I asked him if it made him think about his dream differently, and he said, yes, it made his dream kind of funny, too.

Then I asked whether he thought the dreams could be a metaphor for something.

And this is where I am so very, very grateful for Sally Fogarty and the other teachers who were on Sam’s special education team when he was in middle and high school. Sally announced at one of the annual planning meetings that Sam’s speech had come along enough that he would pass the usual tests meant to detect deficiencies. But, she added, we all knew that Sam’s language skills still needed work. She suggested that she administer another diagnostic test and develop a plan that would help him with more abstract language skills–analogies, idioms, metaphors and the like.

A few years later, Sam and I happened to be driving into Fort Worth and a billboard in Spanish caught our eyes. I read the billboard and understood the words, but I didn’t understand what the billboard was saying. I asked Sam, who was also studying Spanish, if he understood the billboard, because I couldn’t. And he said, “Well, that’s because it’s an idiom.” And then he told me what it meant. That was 15 years ago, and it still makes me tear up.

Sam agreed dream driving could just be the general way we feel about how our life is going, and maybe we don’t need to worry that we can’t always steer, and honestly, we don’t want to stop.

Book report

Over the past ten days, I went back to read a book that had been recommended many times but I hadn’t until now: Clara Parks’ The Siege.

Her book is a parent memoir, but in a class by itself. If I had read her book when Sam was first diagnosed, many pages would have been dog-eared and worn for her wisdom. Parks was an English teacher at Williams College and had her master of fine arts degree. In other words, she knew the value of keeping a daily journal, and thinking critically about what was happening in her family, and applying what she knew about language — and how it was different for her daughter, Jessy (Elly in the book’s first edition) than her other, older children.

I was struck by how many experiences we had in common. Both Sam and Jessy proved their intelligence in unusual ways, which required their families to pay attention. They both kept elaborate maps in their head that allowed them to return to a place even if they’d only been there once.

Both Sam and Jessy also had distressing episodes with vomiting.

And I will digress at this moment to say that researchers have been far too slow to try to understand this problem. Many, many parents report their young children with autism have distressing digestive problems. Parks wrote about her daughter’s in 1967; it’s not like researchers can say they were surprised. Parks gave the problem enough ink that the skeptical reader knew her own theory about the mystery was just that. But, as far as I can tell, it wasn’t until Andrew Wakefield’s disgraceful paper in The Lancet that funders and scientists got serious about understanding digestive problems that children with autism have. Besides faking his numbers to gin up the vaccine connection, Wakefield went into that vacuum of knowledge about autism and digestive problems to give his idea that same sticky quality you find in urban legends.

A publisher once told me that he gets pitched a lot of parent memoirs. He doesn’t publish them any more. They don’t sell. That’s sad. It’s not that Parks’ memoir is the be-all-end-all (although I suspect that if I’d read her book as a young mother, I would have been too intimidated to write one of my own.) But I don’t think we’ve even begun to scratch the surface about what parents have observed, and what that might mean for furthering scientific understanding.

For example, Parks’ observations about language were stunning. Speech pathologists likely understand more about language development in children with autism than they did in 1967, but there’s just too much thoughtful description in her book for me to believe that they’ve got it all.

It’s true that it doesn’t have to be a memoir. Maybe there’s another way to capture all those stories and wisdom to make it better for the next generation of parents and children.

A year to be more open and connected

Two years ago, after writing a news story about a few of our clever readers and what they learned achieving their New Year’s resolutions, I did mine differently. A year into my own experiment, I had learned so much that I shared it in a column.

That first goal to not buy anything (with reasonable exceptions for food and fixing things) reinforced a simpler, more sustainable life. My next resolution, “Yes, please,” was meant to be this year’s yang to last year’s yin of “no, thank you.”

The idea wasn’t that “yes, please” was permission to give into impulses or rationalized needs, but to push through whatever had been stopping me from trying something new. How else to see the world unless you push through to the other side? I made a list of about a dozen challenges that have been nagging for years; for example, learning to better maintain my bike, sew upholstery, broaden my computer skills, speak conversationally in another language, and make cheese. But if something new crossed my doorstep, like when my friend and brilliant textile artist Carla offered a day of indigo dyeing, I said “yes.” I said yes whenever I could.

Not only is life simpler and more sustainable, but it’s also richer and more fun.

That brought the social media expression of my life into sharp relief. For the coming year, I will co-opt Facebook’s stated mission, to be more open and connected, by quitting Facebook.

The main reason to shut down my account is one that has nagged me for a long time. Facebook’s real mission is nothing like its stated mission. For example, I’ve noticed there are people you cannot reach any other way than through Facebook. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. In Texas, we might share a lemonade on the porch and we’re cordial, but we just don’t invite everyone inside. So I would argue that when you can’t reach someone except through Facebook, then you aren’t really connected at all. Facebook is managing your relationships for you through the veneer of being “open” and “connected.”

I set up the Family Room blog as a place to explore ideas related to living with autism. It’s interesting that most readers come here via a Facebook link and will return to Facebook to comment on the topic, rather than connecting below and creating our own community–which, by the way, is not open to exploitation by a third party because I filter and delete all that garbage.

That’s Facebook’s real mission. And, they “move fast and break things.” After I watched Frontline’s two-part special, The Facebook Dilemma, I couldn’t be a part of it anymore. American newspapers are struggling because Facebook (and similar businesses) got the rules changed: they can publish with impunity while newspapers must continue to publish responsibly. It’s expensive to be a responsible company. But it’s worth it because, for one, the truth is an absolute defense. And people don’t die in Myanmar because you got so big moving fast and breaking things that you can’t clean up after yourself anymore.

It took Sam a while to accept my decision. He was worried that my exit would affect his experience. I respect that very much. People with disabilities need help living lives that are more open and connected. He finds community activities through Facebook. Because he can scroll at his own pace, he can absorb and react to more news that people share. He’s not impervious to the third-party nonsense, but he’s not going to show up at a fake rally meant to destabilize the community.

I’ll still be on Twitter because I use the platform for my job and I can’t escape it. And I know my departure from Facebook may affect my coworkers, so I will work to ameliorate that. I hope that readers who want to continue to be part of Family Room will use the green button below to bookmark the blog and come back once a month or so. This blog isn’t going away even though the Facebook teasers will.

My first objective will be to use my words to be more open and connected. Family Room will be one place to make that happen, along with all of the other ways we’ve always had to connect with each other (insert mail-telephone-plus-ruby-slippers icons here!)

My second objective will be that when I have something to share, I will share it with the person I believe would appreciate it most.

My third objective will be actively listening to others in the coming days and weeks. Because the best way to connect is to respond.

Sam taught me that.

Sustainability

Earlier this fall, I was able to spend some time with a local biologist studying quail. I learned more in the course of that day than I was able to put in my newspaper story, which often happens.

The biologist has been working with area ranchers on ways to keep the prairie vital both for their cattle and the quail. On the drive back from Clay County, I saw all the ranches in new ways. Some looked like the ranch we had just visited, lush and vibrant. Others looked used up. I smiled to myself about our farm. When we sold it, our place looked like the former, not the latter.

The biologist started telling me a story about how he’d approached one rancher to bring his land into the quail “corridor.” The rancher agreed, but on one condition: it couldn’t cost him any money.

I could tell the biologist planned on telling me this story a certain way. After all, he was trying to build a big research program and do this good thing for the environment. He needed money for his labs and the students helping with the research. They were bringing new and important scientific knowledge where it was badly needed. The reality likely was this: a rancher that needs to make a change after doing things a certain way for years and years probably needs to spend a little money to get it back right.

Before the biologist got to the big finish in his story about the rancher, I blurted out, “so, really, he asked that whatever you proposed for his ranch be truly sustainable. Because for the changes to last, they can’t keep costing him money, right?”

(This is why people don’t invite me to dinner parties. I’m impertinent. I ask questions that stop the conversation.)

The biologist finished his story, telling me that it took awhile to make the changes to help the quail and figure out the true costs, but ultimately, the rancher didn’t lose any money running his cattle that year. The biologist had delighted in the discovery. But, I could tell by the many long and thoughtful pauses that came after I asked my question that he hadn’t thought about the sustainability of his quail program that way.

We didn’t farm our place with some lofty, progressive, green ideal of it being “sustainable.” We just knew we didn’t have any money and that anything we did needed to be harnessing and directing the little energy we, or the land, already had.

When we tried to help Sam learn to talk and become the marvelous person he was to become, we tried not to focus on hoarding resources. We just tried to harness and better direct the energy we, and he, already had. It worked pretty well.

Sustainability. Its a powerful word. We are starting to use it a lot. I’m not going to let it lose its meaning for me.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #295

Sam (to the dog, on the anxiety triggered by aging eyesight): Gus, you’re a ‘shadow of a doubt’ dog now.