Uncategorized

Take it to all four corners

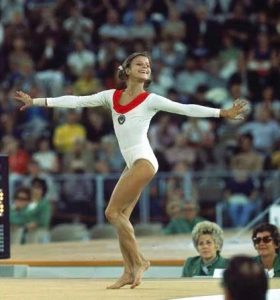

Olga Korbut changed the face of gymnastics when I was in junior high school. She looked so graceful and athletic in Seventeen magazine’s photos from her performance at the 1972 Olympics. As you might imagine, many of the wiggly tweens in my gym class were excited that our teacher added a gymnastics unit, largely because of what Korbut had inspired. Now, we could all experiment with moving through the world that way. That’s also when I learned one of the rules of floor exercise: a gymnastics routine can borrow from dance and mix in lots of tumbling, but it must also go to all four corners of the mat.

It’s a curious rule, yet wise when you think about it. It requires the competitor to be thorough as they challenge their body. I started thinking about that rule again recently and decided to add it to my ongoing pursuit of small, yet large, New Year’s resolutions. For 2021, I plan to take things to all four corners.

Last year’s resolution, Wear An Apron, feels prescient now, given the pandemic. We certainly spent a lot more time in the kitchen in 2020. But the bigger idea behind it–that whatever problem we faced, someone out there solved it already–kept us grounded, too. Online, we found Khan Academy to help Sam (and me) learn calculus as well as a sewing pattern and instructions for face masks vetted by some pragmatic nurses in Iowa. On YouTube, I started following a smart yoga instructor and my dad’s favorite backyard gardener, a fellow in England whose bona fides begin with his unapologetically dirty hands. Even streaming The Repair Shop revealed wide-ranging wisdom about problems I didn’t even know could be solved. Awesome.

Thinking ahead to this year, I remembered an editor who would remind us reporters to nail down all four corners of an investigative story before publication. Smart advice, but it also created a defensive image in my mind’s eye rather than something inspired by filling up the space of a gymnastics mat. Don’t get me wrong, it’s important to be able to rigorously defend your choices and actions, but the big idea for 2021 shouldn’t be about the pursuit of perfection. Instead, going to all four corners means planning thoroughly, and being careful and deliberate.

Raising kids, especially someone like Sam who needed so much, shunts the pursuit of perfection to the side in favor of steps that move toward progress. But I can’t say we always took it to all four corners.

For example, Sam does pretty well in the kitchen. All my children learned cooking and cleaning basics and food safety. Now, Sam does so well with some recipes that I can plan time off in the kitchen when he steps up. But I know we haven’t taken it to all four corners. Managing a kitchen is hard with all the planning and shopping. And the principles of cooking that let you tackle a new recipe, that’s something else, too.

So, not such a small idea after all. But it may be warranted for 2021, because I bet once we let loose the reins from the pandemic, there could be many things that need to be thought through again, and to all four corners.

Intention makes the little, big

One of Sam’s first speech therapists missed many scheduled home sessions. Early childhood programs usually begin in the home for toddlers who need services like Sam did. By the time I thought I should complain about her absences, however, Sam was “aging out” of the program. Once a child reaches 3 years old, education officials offer preschool along with speech and other services. Preschool offers a far richer environment to learn much more and much faster — as long as your child is ready to learn that way. Sam went to preschool where another speech therapist was assigned to work with him. She kept her schedule.

I’ve been thinking a lot about our family’s first autism experiences as Shahla and I put the finishing touches on our book. Given what could have been for our family 30 years ago, I feel really lucky.

It’s odd to call it lucky that Sam missed so many of his first speech therapy sessions. I didn’t consider it lucky back then. Sam had just been diagnosed. There was a lot of work to do. The therapist wasn’t doing her part of the work.

Yet, when she did keep her appointments, they were powerful. She took time to explain to me what she was doing as she worked with Sam. She wanted me to understand and keep things going when she wasn’t around. Since she missed so many of her appointments, I pivoted toward that goal pretty fast. (Honestly, I think she was battling depression.) I wasn’t a trained speech therapist. But I was soon thinking about Sam’s speech development all the time and responding to him in those thousand little moments you have every day with your child.

It took a while to see how lucky that was.

Sam was in primary school when I met Shahla. Shahla also helped with his progress, but that, too, took a while for me to see. There was still a lot of work to do and I was always trying to line up help. Shahla and I would chat occasionally about how things were going. I would share a story of some happening, often whatever was vexing us at the time and she would explain what was going on behind the curtain. Those little conversations were actually a deep dive for me. I understood better what was happening with Sam and where to go next — just as his wayward speech therapist was trying to show us.

We were learning to work smarter, not just harder, of course. But there was something else.

Sam couldn’t be forced or coerced — not that we wanted to work that way. Like many children with autism, in my opinion, the ways that he protected himself from the outside world were effective and strong. Still, we made progress. His best outcomes came after we approached things in a straightforward way with his full participation. The better we got at being deliberate, respectful, and intentional, the more momentum we created.

Even though Sam is a grown-ass man, we still seize the small moments to make a difference. I’ve been working at home for a while now, and that’s come with more opportunities for those small moments. With Mark gone and both Sam and I working full-time for the past decade, we didn’t have many. These days, we can chat over breakfast or lunch (or both) before Sam heads to work. Like every young adult, Sam sometimes turns his adult mind back to childhood experiences and tries to make sense of them. I’m glad to be here as he puzzles through all that. I’d like to think he’s puzzling through more because of these opportunities.

These days, he’s also been thinking a lot about why alarm bells bothered him so much when he was in elementary school. I told him he wasn’t alone, that no one likes that sound. That was a revelation to him, since apparently the rest of us hide that aversion so well. But he’s really wrestling with this, breaking things down into the science of sound, analyzing sound waves, and figuring how to manipulate them. He wants to make his own science to help others who hate alarm bells as much as he did. Who knows? Maybe he’s got something like Temple Grandin’s squeeze machine going in his sound lab back there, ready to banish those anxiety-making monsters once and for all.

Happy progress, indeed.

Community of practice

I finally moved my personal things out of my old office space, thanks to the help of a co-worker who also had to listen to me prattle on about things like how many piano makers there were before and after the Great Depression and why that might mean something to journalism now.

I have a century-old, upright grand piano. My parents got it for me when I was first learning to play. It has a big sound, especially after I had it rebuilt about ten years ago. The man who rebuilt it told me that before the Great Depression there were more than 400 piano makers in the United States. After the Great Depression, there were just two.

That seemed a stunning loss to me. Many people love music and enjoy playing, even if just for themselves. Pianos are among a handful of instruments that play both melody and harmony. However, our attention is never guaranteed, and our money usually follows wherever our attention goes.

That same drifting attention is happening to the news business now. Businesses needed your attention, so they got it by putting their advertisements next to news. Newspapers were among the original public-private partnerships. The better quality the news — a real public service at that point — the more valuable that space got. That is, until our attention started to drift.

One of the Denton newspaper’s most popular reports was the police blotter, at least before the pandemic began. It had long been a guilty pleasure for readers. Of course, now they can find even more guilty reading pleasures on Facebook, a company only too happy to hoover up the advertising revenue as people’s attention drifts over there. Probably in another year or two, there will be only a handful of news outlets left because the business model that extracted value out of our attention has changed so much.

Some people have finally figured that out, that the business model now is for people who recognize they need solid journalism to make sound business decisions and to make good public policy decisions.

Without that, we will soon have warlords squabbling for years while ticking time bombs sit in our harbors.

I’m ready to stop thinking about the business model and start thinking about the community of practice — journalists are a group of people concerned about the quality of information, how it’s gathered and vetted, and how to do it better, and the best way to do that is by debating all those values regularly among your peers — and then publishing or broadcasting.

This community of practice in journalism is also the same thing that people like to criticize as “the priesthood” or the “legacy elite” or “media bubble” or whatever other pejorative they want to hurl at the wall that might stick for the moment. But humans create communities of practice because they care about what they do and want to do it better, and scholars are beginning to recognize how much this phenomenon has helped all kinds of businesses do better and make progress in our modern world.

My first introduction to communities of practice came in the autism world, with parents sharing wisdom and such. Eventually, parents started seeing that the best therapists with the most powerful ideas kind of hung out together and fed off each other’s practice and research. No one was talking to you about a “community of practice,” but if you wanted the best for your child, you always wanted to be close to that, since chances were higher that your kid would benefit from all that supercharged brainpower and skill.

I encouraged Michael and Paige to find the equivalent as they ventured out into the working world, although I didn’t have the vocabulary for it at the time. At the University of Iowa, they organized the dorm into micro-communities that way and Paige fell right in. She’s still friends with many of her original writing community. Michael got a power introduction to the concept as a behavior tech in the autism world. He’s like a heat-seeking missile for that value where he works.

Journalists sometimes compete with each other, but we benefit from each other’s successes and critical takes on each other’s work. The successful business model(s) will depend on the rigor within our community of practice. As business models disappear and fail, that doesn’t mean the community of practice must also, but it makes it a lot harder. Until the emerging business models stabilize, our environment is ripe for propaganda disguised as news. But if our community of practice disappears, no business model will save it.

Just like the piano makers.

The original in social distancing

I have to admit that Sam surprised me a little when he came home from work one night and said that social distancing was hard. He’s always kept a healthy distance from others.

But I could understand, too. People are buying a crazy amount of stuff in the grocery store. He and his co-workers are really hopping to keep up.

I asked him whether he remembered his perfect attendance in middle school. He got a special award for never missing a day from sixth through eighth grade. I told him that by middle school he’d gotten so good at keeping his distance from others that he never was close enough to get the germs. He had a good laugh about that.

Sam didn’t like to be held as an infant or toddler. At first, it was hard to figure out how to comfort a child who couldn’t stand to be hugged, or touched, or sung to. Eventually, we discovered things that worked and, as he grew and changed, discovered even more.

As an adult, Sam has a way of attending in a conversation – a sort of standing up straight, full soldier attention to your presence – that even if he never shakes your hand, or hugs you, or even really makes good eye contact, you somehow know that he is truly present. It’s such a gift to have learned that from him.

And when you are being present, you know when the other person is present and responsive to you, too. When I’m out running or walking with the dog, or making a brief trip to the grocery store, people are doing what Sam does (although maybe with a little more eye contact) as they reach out to chat these days and that doesn’t feel socially distant at all.

It’s in the moment, present, responsive.

I hope it never goes away.

Learning from the world around you

Young parents recognize when the kids start to absorb information from the world around them and (we hope) act accordingly. Kids are watching and listening and thinking and so you’ve got to take a little more care with the grown-up stuff.

We’ve got to let the rope out eventually, since the kids need to fly on their own. But we might not want to be the scary one with all that grown up stuff, because life’s pretty scary on its own.

The ability to absorb from the environment didn’t work the same way for Sam as it did for his brother and sister. As a child with autism, his attention could be hyper-focused or super-zoned out. When he was a toddler, we were never quite sure how much he absorbed from what was going on around him. But over the years, we coached and cued. We became more confident he was seeing what he needed to as he grew up and responded.

(For example, we worried at first that he didn’t understand traffic and would never watch for cars. Eventually, he proved he could and would learn to drive.)

I’m not sure what helped him recognize that important things he needs to know come in small, even sneaky ways. Over the past year or so, I’ve watched him notice small things going on around him far more than he used to. He’ll pick up the newspaper from the table and read a bit because the headline grabbed his attention. He might make a comment about the story over breakfast.

He’s learned when to ignore email and when not, which really a miraculous thing when you think about it. He still doesn’t like opening his snail mail (to be truthful, I don’t either, so what is with that?) but when he sees the envelopes that matter, he doesn’t truly ignore them. He knows what’s inside and opens them when it’s time to pay the bill or renew the tags, etc.

A few days ago, he saw a flier advertising a Social Security workshop in the pile of mail. He asked a lot of questions. He’s still healing from the stress of repaying a substantial amount of benefits last year. We knew when he got his full-time job at the warehouse that his benefits could finally end. We happily went down to the Social Security office and gave them notice, but it took months for them to stop sending checks. I cautioned Sam to sock that money away — they would eventually ask for it back. They did, and he was ready, but it was still really stressful for him.

He thought perhaps the flier came from Social Security and he needed to attend. I’m not sure if there’s a rule of thumb to help him wade through that type of information. I’ll think about it. But in the meantime, I told him, ‘nah, that flier was for me because I’m getting old.’

.

The children are watching

Sam and I enjoy going to the movies once a month or so. We are lucky that two theaters with lounge seating are within an easy biking distance, including our newest favorite, Alamo Drafthouse.

Sam’s not a fan of action films, or films with dark themes. That includes super-hero movies, although he took a chance and really enjoyed Spider-man: Into the Spider-verse. (Best. Movie. Ever. But I digress.) We both enjoy a good story well told, which means, for starters, that we don’t miss anything by Pixar.

Recently, we went to see Peanut Butter Falcon. I knew we were taking a chance that story could come up short. Hollywood likes its tropes, and stories that include people with disabilities can be super-tropey. But the star, Zack Gottsagen, has Down syndrome and the movie’s writing and directing team had a clear, deep understanding of self-determination for people with disabilities.

The story resonated with Sam. I watched Rain Man again recently on Netflix, and Sam drifted in and out of the room as it played. Dustin Hoffman was brilliant but he doesn’t have autism – and that matters. After Peanut Butter Falcon, Sam and I talked a lot about the story and the characters. We talked some after Rain Man, but not as much as with Peanut Butter Falcon.

Then I stumbled upon another movie, Keep The Change, which features actors with autism. The story line was authentic. Sam got to see adults with autism fall in love, and I cannot tell you what a gift it is to have that on the screen.

Movies are better when our world is fully reflected on the screen. In other words, a story will come up short if the character with a disability is there primarily to challenge the protagonist’s humanity. Movies, like any media, imprint and reinforce social constructs. I’m rooting for the stories that push our humanity toward justice – and love.

How to raise a hater

Three years ago, I saw a window into how you raise a hater. It was at, of all places, the movies.

I talked with my daughter, Paige, about it. She was there. She didn’t hear what I did, but she heard something else like it. I shared my experience and insight with Shahla. She encouraged me to blog about it, but the words got stuck. A lot.

When the world is full of haters, it’s not a good place for Sam and people like him, who need us to be our best selves. People are loving and generous for the most part, but I’ve seen the dark side, too. It’s easy to feel noble and loving and generous when it doesn’t really cost you.

After a white boy drove to El Paso in order to shoot innocent people yesterday, the words finally started to flow. We talk about preparing for mass shootings in the newsroom. We know we must. There’s nothing about our community that’s special. The haters are here.

Three years ago, I watched a father teach his son how to be a hater.

Oh, it wasn’t obvious. The boy didn’t even know he was being taught to be a hater. And the father didn’t know he was teaching it, either.

To get passed down, these things have to go slow. A father loves his son and wants to be loved by his son.

A trailer played for Hidden Figures, the movie based the early days of NASA and the first flight to the moon. I sat next to the father in the movie theater. The trailer made him uncomfortable. In between stunning images of rockets blasting through space, hints of the little-told story about the pivotal role that black women played in the program unfolded. He could bear it no longer. He leaned over to his son, who was probably 8 or 9 years old, and said, “We won’t be seeing that.”

I knew why he was uncomfortable. But his son didn’t. After all the previews played, the father said, “There are lots of good movies to see.” And the son added, “But not that space movie.”

A boy loves his father and wants to be loved by his father.

We were all there to watch Moana. Did the father not know what this Polynesian legend was about? Apparently not, Paige said, because after the movie he kept asking his wife: but where did they come from?

The father had too much discomfort. A family has to find a place for the discomfort when father is afraid. The needs of the one outweigh the needs of the many. To get passed down, these things have to go slow.

Our kids will do things, learn things, seek things that make us uncomfortable. We have to let them. They will still love us. They are becoming their own. They want, and can, do like we did when we were young, and make the world a little better than it was before. If we don’t let them, they won’t be resilient enough to survive all these changes. They will become a snowflake.

Or worse.

A hater.

Fare thee well, feline

It’s been ten days since we’ve seen our cat, Tiger, although I knew the first morning when I opened the back door and he didn’t show that he was gone for good.

Tiger came to live with us as an outdoor cat. He was one of several kittens that a co-worker’s wife found in a box on the side of the road fifteen years ago. We were living on the farm at the time and had been having trouble keeping cats, as often happens out in the countryside. But Paige was 10 years old and pining for a cat, so we picked the male orange tabby kitten for good luck.

Tiger proved to be a survivor. Even as coyotes, owls and other predators exacted their toll on our farm, Tiger knew when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em. When it was time to move into town, I was apprehensive. He’d lived on the farm for more than a decade. I got advice from other cat owners and the veterinarian. On moving day, I was ready with drugs and a crate, but as soon as the moving vans showed up in the driveway, Tiger, ever the survivor, hid out. Two days later, he got hungry enough for the new owner to catch him in the house and call me.

During the transition, he fought against the drugs so it was like having a drunk college student lumbering around the house as we unpacked boxes and filled cupboards and closets and bookshelves. After a week of supervised outdoor time, he started fighting the whole cat-on-a-leash thing. I opened the door and said, “good luck little buddy.” I don’t know what I was worried about. He was a survivor and he knew where he lived. That’s where his food dish is!

Now that he’s gone, I feel the loss, as I knew I would, even though I’ve also known I won’t get any more cats. I’m a dog person. I have been since I was a girl, obsessed with learning all the breeds of dogs and reading stories about dogs and pining for a dog myself.

While our dogs have reminded me of the rewards of loving unconditionally, I have to give props to Tiger, whose utter cat-ness provided insight into life’s more complicated doings and feelings.

He brilliantly established his personal space. Pet him just a stroke or two when he wasn’t feeling it and he bit your hand or arm or leg or foot to let you know. Even when he was willing to sit for a little cuddle time, you still got bit at the end.

He ate ritualistically: every half hour or so, he returned to the bowl to eat several bites. Ergo, we learned to always pause for a moment when we opened the door to let him in (or out) and forever keep kibble in the bowl.

He often joined the dog and I on the first block of a walk. Then he decided either we weren’t worth the effort or going into the wrong territory and he went off on his own.

When Paige went off to college, the cat expressed how distressing the empty nest was by peeing all over the pricey feather bed I bought to deal with a too-hard mattress. I didn’t even try to recover anything. The feather bed got tossed in the trash. I still sleep on that too-hard bed.

Farewell, old friend. We’re glad you came to stay.

Cycling close to the sun

Sam said he liked the country roads best on our family bicycling trip to southern Italy. There are 60 million olive trees in Italy and I do believe we pedaled past a hefty percentage of them.

In this photo, you can see he stopped next to an olive tree that was a thousand years old. Some of them look great. Others are succumbing to a bacteria that came over with an insect stowed away on South American-made pallets. Many of the olive groves are small, family-owned plots that produce enough to supply the family with a little more to share. (You can buy olive oil in Italy the way we buy craft beer here in the U.S.)

On the backroads, you can trade that ten-European-cities-in-seven-days experience for a different kind of intensity. What’s not to like when you share miles of road lined by stone walls with just the occasional tractor or Italian nonno driving his 1967 Renault Quattro to the village? The roads weren’t perfect, but Sam didn’t mind dodging the potholes. Once, along a highway, I watched him drift, ever so slightly, into the main lane so that he could cycle over the rumble strips.

On the backroads, you can catch the fragrance as you pedal by chamomile, star jasmine, ginesta (broom) or the pine trees.

You can see a farmer having a sandwich in the shade of an olive tree. Another farmer stops picking to pass a handful of fresh figs over the wall to a fellow cyclist. Old men sit on benches in the center of the village and wish you “buongiorno!” The village center doesn’t look like it’s changed much at all in several hundred years.

Sam was ready for the routine, having gone on a similar tour last fall in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. We pedaled a good pace and still found time to relax in the swimming pool after covering 20-30 miles each day. Nobody lost anything along the way. The only real drama came the last day. A driver honked and then turned right in front of Paige, thinking that Paige would stop (uh, NOT) and then nearly hitting her on her bike. One of the tour leaders detoured to yell at the driver. The moment was so quintessentially Italian that I couldn’t help but live vicariously through the movie she was making for me right then and there.

Sam downloaded two dictionaries before we left the U.S. and explored the language often. He always tried to order in Italian. Periodically, he also thought of things that would increase our comfort and success in living out of a suitcase for days at a time. He inspired me to start a new checklist for our next trip — when or wherever that might be. At one point, he told me he thought he could take the next tour by himself.

He probably could, but that was never a goal of these trips. Traveling brings new perspectives. We bring some of the romance home by letting the experience change the shape of our daily lives. Sam grows through travel just like the rest of us, only a little bit more. He has always cycled a little closer to the sun.

Cake for breakfast

Early on during our bicycle trip in southern Italy, Sam announced a goal: he was going to try all the seafood he could. That was daring.

The first day, our trip leaders asked whether anyone in the group had food allergies or preferences that they needed to know. Sam’s preferences are idiosyncratic, but they aren’t hard to work around. It was easy enough to tell them that for welcome cocktails, “no alcohol, no bubbles” works for Sam. The bartenders seemed to enjoy the challenge putting together fun juice combinations for Sam. He also doesn’t like fresh tomatoes, although tomatoes cooked into sauces are ok. Even so, when something came out of the kitchen with a tomato or two – the Puglia region is famous for its cherry tomatoes – he was a sport about it.

But the seafood goal was something else altogether. The first time I can recall him being deliberately additive, not restrictive, about food. He studied entire menus in his quest. He picked classic Italian dishes: a plate of mussels as a starter, pasta with clam sauce for a first course, a swordfish steak for second. He picked unexpected ones, too, like seafood pizza. He was triumphant when he found octopus and potatoes for dinner at a seaside restaurant in Savalletri.

That’s his photo, by the way.

It’s hard not to be sentimental about how far he’s come. Sam was so food challenged growing up. As a preschooler, he would eat only breakfast cereal morning, noon and night. He hit his big growth spurt at age 15 and even though he was hungry, he limited his food choices and still refused meat. We came close to taking a second mortgage out on the house in order to pay for an intensive intervention program at Ohio State, but he turned a corner just in time. Given enough ketchup and Parmesan cheese, he started broadening his choices. Instead of eating the edge of the bun all around the hamburger, he ate the whole burger.

(Puglia restaurants are surely restocking their Parmesan supply now that we’re back home. But to be fair, he didn’t cover everything in Parmesan. We let him know which Italian foods didn’t lend themselves to that and he was happy to try without.)

Paige and I had our own dining wish lists, although we were never able to make good on eating tiramisu in Italy. The dessert at the end of the meal was usually the chef’s choice. Sweet semifreddi, gorgeous gelatins, mille-feuille — it was hard to get upset about that.

We didn’t expect that the choice of dessert sweets would be plentiful at breakfast, but there you have it. Italian masserias place many different cakes and crostada on their breakfast buffets.

We were cycling 20-30 miles a day. Heck, yeah, we had cake for breakfast.