problem-solving

The Power of Parmesan Cheese

Sam was very young when he discovered that Parmesan cheese made almost anything taste better, and it became a thing in our family.

We would tell the wait staff at Olive Garden, for example, to please leave the twirling grater at our table, because they had other tables to tend to and they didn’t need to spend all their time grating cheese for us.

(Now, foodie friends, please don’t judge. We were thrilled that (1) Sam finally could not only tolerate but enjoy a dinner out with the family and (2) the kids were asking to order things beyond a hamburger and fries.)

When Sam was little, he had distressing vomiting episodes. The doctors were no help. He eventually whittled his food choices to cold breakfast cereal with milk, morning, noon and night.

After a few years, we stumbled on the power of Parmesan. For Sam, the cheese was a gateway to trying other foods. Parmesan helped restore a balanced diet for him, including vegetables and salads. We didn’t blink at the amount of Parmesan that flowed. We even bought a twirling grater. On our family vacation in Germany last summer, we came across cheese mongers selling massive wheels of Parmesan and we teased Sam, “dude, that’s what you need to buy for a souvenir.”

I used to liken his preference to the way some people think everything tastes better with a little ketchup or mustard. For Sam, it was Parmesan, and we figured that was that.

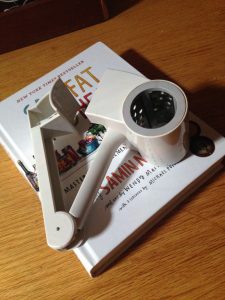

Then along came Samin Nosrat and Salt Fat Acid Heat. In her Netflix series, she talked about the first time she was a guest at a traditional Thanksgiving dinner and how she found herself slathering the cranberry sauce on everything because the meal lacked the acid her palate craved.

Then along came Samin Nosrat and Salt Fat Acid Heat. In her Netflix series, she talked about the first time she was a guest at a traditional Thanksgiving dinner and how she found herself slathering the cranberry sauce on everything because the meal lacked the acid her palate craved.

In the episode in Italy, she spent considerable amount of time exploring how Parmesan cheese was made and what powerful things it can bring to a dish–fat, acid, salt. She told viewers that good Parmesan should be among your kitchen staples.

No worries, Samin. We got a big check mark on that one in the kitchen at Chez Wolfe.

Horsemanship as culture

When we first moved to Texas from California, I was struck by the fact that Fort Worth’s cultural district put world class arenas and art museums side by side. At the time, I thought we would be more frequent visitors of the latter. That was upside down.

Watching Sam’s ride in “working trail” events, you can see how many cultural conventions there are in horsemanship. Some of them I understand. Some of them I don’t. Sam learns what’s expected of him as a horseman without a lot of extra chatter, which in itself is a cultural convention.

He does well with this pattern, but his horse, Smut, resists him at the gate. He keeps at it until the judge times him out. I’ve watched him persist at the gate before. He shows unlimited persistence when there’s no time limit. When I start unraveling in front of a problem, I remember how he persisted as a baby, toddler, student — including college — and somehow all the frays just go away.

Internet commerce is a wild web

If Sam wrote up his tips for how to avoid getting scammed, it would read something like this.

- Don’t read email

- Don’t respond to texts

- Don’t answer the phone

- Open snail mail only after your mom nags you for a week that it’s important

And still things happen to him. I try not to hover. He’s a grown-ass man. He managed to handle something this week that would make Dave Lieber and his Watchdog Nation proud: he got a refund from a seller on eBay.

Sam is working on backing up his computers cloudlessly. It means he needs some external hard drives, and some redundancy. It’s a good project for him. One of the devices he bought for the project wasn’t the right device. He sent it back to the seller. He got proof that he sent it back and the seller received it. But the seller was very slow in refunding his money. It was a lot of money–$120 or so. He complained to eBay and then he went over to his bank to see what they could do. This is where I give a big shout-out for the power of local banks who get to know their customers, because they helped turn up the heat with PayPal. Sam announced this morning that eBay is refunding his money.

Sam said, “I was starting to think that the seller wanted to sell me the wrong item and keep my money.”

That’s an excellent demonstration of being able to take the perspective of another and act accordingly, something that is hard for people with autism to do.

I told him that eBay and other e-commerce platforms need sellers to be honest or their platform becomes irrelevant. I used to not tell Sam things like that. But, he’s getting the hang of this seeing-situations-from-another-person’s-perspective thing.

He still wants a better consumer tip sheet, and he’s got a point. When he was at the bank, he learned about “verified sellers.” In the 23 years eBay’s been around, I think I’ve bought two things on that platform. I really have no idea. I’ve got my homework for the week.

And, if anyone has good consumer tips about eBay, please leave them in the comments below.

A year to be more open and connected

Two years ago, after writing a news story about a few of our clever readers and what they learned achieving their New Year’s resolutions, I did mine differently. A year into my own experiment, I had learned so much that I shared it in a column.

That first goal to not buy anything (with reasonable exceptions for food and fixing things) reinforced a simpler, more sustainable life. My next resolution, “Yes, please,” was meant to be this year’s yang to last year’s yin of “no, thank you.”

The idea wasn’t that “yes, please” was permission to give into impulses or rationalized needs, but to push through whatever had been stopping me from trying something new. How else to see the world unless you push through to the other side? I made a list of about a dozen challenges that have been nagging for years; for example, learning to better maintain my bike, sew upholstery, broaden my computer skills, speak conversationally in another language, and make cheese. But if something new crossed my doorstep, like when my friend and brilliant textile artist Carla offered a day of indigo dyeing, I said “yes.” I said yes whenever I could.

Not only is life simpler and more sustainable, but it’s also richer and more fun.

That brought the social media expression of my life into sharp relief. For the coming year, I will co-opt Facebook’s stated mission, to be more open and connected, by quitting Facebook.

The main reason to shut down my account is one that has nagged me for a long time. Facebook’s real mission is nothing like its stated mission. For example, I’ve noticed there are people you cannot reach any other way than through Facebook. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. In Texas, we might share a lemonade on the porch and we’re cordial, but we just don’t invite everyone inside. So I would argue that when you can’t reach someone except through Facebook, then you aren’t really connected at all. Facebook is managing your relationships for you through the veneer of being “open” and “connected.”

I set up the Family Room blog as a place to explore ideas related to living with autism. It’s interesting that most readers come here via a Facebook link and will return to Facebook to comment on the topic, rather than connecting below and creating our own community–which, by the way, is not open to exploitation by a third party because I filter and delete all that garbage.

That’s Facebook’s real mission. And, they “move fast and break things.” After I watched Frontline’s two-part special, The Facebook Dilemma, I couldn’t be a part of it anymore. American newspapers are struggling because Facebook (and similar businesses) got the rules changed: they can publish with impunity while newspapers must continue to publish responsibly. It’s expensive to be a responsible company. But it’s worth it because, for one, the truth is an absolute defense. And people don’t die in Myanmar because you got so big moving fast and breaking things that you can’t clean up after yourself anymore.

It took Sam a while to accept my decision. He was worried that my exit would affect his experience. I respect that very much. People with disabilities need help living lives that are more open and connected. He finds community activities through Facebook. Because he can scroll at his own pace, he can absorb and react to more news that people share. He’s not impervious to the third-party nonsense, but he’s not going to show up at a fake rally meant to destabilize the community.

I’ll still be on Twitter because I use the platform for my job and I can’t escape it. And I know my departure from Facebook may affect my coworkers, so I will work to ameliorate that. I hope that readers who want to continue to be part of Family Room will use the green button below to bookmark the blog and come back once a month or so. This blog isn’t going away even though the Facebook teasers will.

My first objective will be to use my words to be more open and connected. Family Room will be one place to make that happen, along with all of the other ways we’ve always had to connect with each other (insert mail-telephone-plus-ruby-slippers icons here!)

My second objective will be that when I have something to share, I will share it with the person I believe would appreciate it most.

My third objective will be actively listening to others in the coming days and weeks. Because the best way to connect is to respond.

Sam taught me that.

No going back

Sam lost his sunglasses in Germany.

There wasn’t anything remarkable about the sunglasses themselves. They were a pair of sunglasses that had been lying around the house for years, a little scratched, but durable both in their purpose and their terrific ability to avoid getting lost the way most sunglasses do.

Sam, myself, Michael and Paige on the Lake Constance bike trail from Bregenz, Austria, to Lindau, Germany.

The loss, though, became a valuable lesson for our family.

I knew the trip would challenge us, biking more than 150 kilometers over the course of five days. At the end of the first day’s two-hour ride, Sam turned to us and said he was confident that he had trained enough for the trip.

He had been a little nervous about it, but we set out on hourlong rides several times a week in the months before. Inspired by Michael, he also hooked his bike up to a wind trainer for regular spins.

The third day, our second full day of riding, set out as our longest ride of the week. We left our hotel in Lindau to cycle to our next hotel in Uberlingen. Most of the people in the riding group took the shortcut, taking the ferry from Friedrichshafen to Meersburg to finish the ride. We met the group and told the tour leaders that we wanted to cycle through the orchards and vineyards rather than ride the ferry.

About halfway to Meersburg, we stopped to refill our water bottles and have a snack. Sam asked where his sunglasses were. He thought someone had grabbed them for him in Friedrichshafen, where we all took a bathroom break.

No one had. Sam asked if we could go back and get them. Michael told him, “Sam, there’s no going back. We’re already pretty far from Friedrichshafen, and we’re riding 40 kilometers today.”

Sam protested briefly, but got back on his bike and plowed ahead. When we arrived at Meersburg for lunch, he was still upset. We sat at a table beside the lake and Sam tried to explain. It wasn’t going well and people were starting to stare. I invited Sam to take a walk with me to the water’s edge so he could collect his thoughts and I could make more room for listening.

There was another family walking on the little beach with their German shepherd. They threw sticks into the waves. The dog wouldn’t venture past depths over its head, but it worked hard to bring back every throw.

Eventually, Sam was able to collect his thoughts.

He understood that sometimes we help him out as a trade-off, to get things moving faster, especially when being slow is risky. But when he is responsible for himself, “I need more time,” he said. And he said that it was clear to him on this type of excursion, a person has to be responsible for themselves.

Most of us human beings don’t have enough self-awareness to assess these kinds of scenarios, let alone ask simply and directly for the fix. Sam constantly amazes me with this gift of his.

We went back to the table and announced the findings. We all agreed we could and should slow down our transitions. Paige asked Sam about a checklist. What if each of us went through a checklist, like an airline pilot, before we cycled on? The process helped us slow down for Sam and, at one point, also kept me from losing my cycling gloves. We often were the last ones of the cycling group to leave, but because we rode fast, it all worked out in the end.

I told Paige later that day that I did have a secret hope that the trip would stretch the family, although I wasn’t quite sure how. I hoped we wouldn’t be miserable, but I didn’t worry about it either.

Learned helplessness does someone like Sam no service at all, and some of that was coming from our habits to take shortcuts and speed things up. He deserved more from us. We learned we could step back, let some conflict points rise up and not freak out. After all, Sam is a grown-ass man.

Ok, Germany, alles klar

The kids and I just finished a week of bicycling in the Bodensee region of Germany, Austria and Switzerland Saturday, arriving home Sunday night.

We had a wonderful time. There was good wine, great cheese, and lots of beer, too. This is the second time I’ve explored another country by pedaling the backroads with a small cycling tour. I cannot recommend the experience enough. Paige and I got to know Ireland while cycling the “Wild Atlantic Way” last year. Michael and Sam joined us this year cycling through Alpine farming villages and along the shores of Lake Constance.

We did our best to speak German to the locals, respect the rules of the road and be all-around good representatives of our country. We tried not to be obnoxious Americans, but that’s harder than you think. We each had our moment (well, except maybe Paige) where we stepped in it at least once.

My chance came the second day of riding. It didn’t take long to realize that bicycling is king in Germany. So many people in Germany ride themselves that they see and respect cyclists when they are driving. But they also are efficient people. Leave a gap in your cycling group and they will fill it in the roundabout. Our first big run through a traffic-filled roundabout, I left a gap but kept going trying to catch up to the group. A driver took my hesitation as his turn to enter, but braked at the last second (thank goodness). As I pedaled on through, he yelled at me in German. I tried to give him “I’m sorry, I’m from out of town” smile, but I don’t know if those are universally understood.

Michael’s turn came the third day of riding. We parked our bikes at the bottom of the hill and hiked up to Meersburg Castle. We bought admission tickets for a self-guided tour and managed to enter the first room just as a special guided tour began. We stood politely for several minutes as the tour guide spoke much German very fast. We felt it would be rude to move through before the group was ready to move. But when we did, one of the ladies on the tour stepped in front of Michael and eagerly spoke even more German to him. We were flattered she thought we were so fluent. I again tried to flash that “I’m sorry, we’re from out of town” smile. The tour guide took pity and said the woman wanted us to know that they had paid extra for the guided tour and we didn’t. Could we please hang back for just a bit? After they moved to the third room, we were able to push on past, which was fine, we wanted to get to the room with all the armor displays anyways.

Sam’s turn came the fourth day. It scared me a little bit. We rode to Reichenau Island and stopped for lunch at a popular roadside restaurant (for what did turn out to be the best fish we ever had). Many other cyclists had the same notion. It was hard to find a place to park your bike out of the way.

Sam had come so far on this tour, taking charge of his gear and following the rules of group rides and the road. He was trying to park his bike tight in, the way a good German cyclist would. He didn’t notice that he was maneuvering in a way that kept another fellow waiting as he was trying to extract his bike and leave. I pointed it out, and Sam got out of the way, but apparently not fast enough. The man decided we were annoying tourists and made a move that would have gotten him punched in the face in the U.S. – he got in front of Sam and stood quite close without moving, expecting Sam to return his reproving eye contact. I held my breath. Sam was tired from our ride. He was fiddling with his helmet and looking at the ground, completely unaware of the confrontational stance in front of him. The guy didn’t know what to do, so he left, muttering German curse words the whole way.

God bless autism.

Gentlemen, start your engines

Sam has had a lot of car trouble lately. He has been driving a 2001 Toyota Corolla that he bought used 10 years ago.

This little car’s early life was in Corpus Christi, which probably means some hard miles in salt air. (We made sure it wasn’t ever flooded before we bought it.) The plastic parts have gotten so brittle, it’s just a matter of time.

Our first big tap on the shoulder was on the way to State Special Olympics a month ago. We blew a tire. Now, that’s no big deal, as long as you can keep your wits about you as you put that little donut of a wheel on your car along the highway in a strange city long after dark. But after we got two new front tires at the tire shop, the car wouldn’t start. For whatever reason, the bushing to the shifter cable broke while the car was up on the rack. We may have hobbled to the tire shop, but we had to be towed to the dealer for that repair.

Fun times.

On Friday, we got another big tap on the shoulder when Sam headed out to work. Turn the key and nothing, nada, zilch. He’d already changed the battery in January. From the problem in Bryan, I knew it wasn’t the shifter cable. And from my own truck’s problem last month, I knew it wasn’t the starter.

Since we would have had to pay for a tow, it was worth the gamble on replacing the ignition switch. Sam inherited his father’s talent for fixing things and, for whatever reason, I’m a fair troubleshooter. It took a few hours, but we knew we’d identified the problem when we compared the old and new switches. The old one had the telltale signs of an electrical short. And one of its three plastic brackets had broken off, likely setting off the slow chain reaction that jostled its way into oblivion.

I have been coaching Sam for months about planning to buy a new, or new-to-him, vehicle. Some of the plastic parts he’s had to replace on the car don’t have anything to do with its overall reliability, but many others do.

People without reliable transportation risk losing their jobs. Our local transit authority, DCTA, stunningly, has zero bus service to Denton’s industrial park where Sam and thousands of other Denton residents work.

I do not know why this is, but I’ll put that on my to-do list at work. (I’m a reporter for the Denton Record-Chronicle.)

Sam is reluctant to retire his car yet, and I can respect that. It still runs well overall. He hasn’t had a repair that’s cost as much as a new car payment.

After Sam finished replacing the ignition switch, the car cranked its Toyota self. He got a big grin on his face. For about $75 he bought himself more time.

For now.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #313

Peggy: You’ve got to keep your boundaries.

Sam (talking about girl trouble): I have really strong boundaries, but she’s put a chink in all of them.

Be the Bumper Guard

After my family moved from the Midwest to Colorado, we started a new Christmas tradition. My grandmother, who lived in Rockford, would send a little cash instead of gifts for Christmas. She forbid my parents to use the money to pay bills. It was to have fun, she said.

So, Christmas Day, we’d all go bowling. As we grandkids had kids of our own, we kept on bowling for Christmas. Some years we’d take up as many lanes as a league would.

Those first few years, it was hard to watch the little ones learn to bowl. They would hit pins, but they would also throw a lot of gutter balls. The year the bowling alley offered lanes with bumper guards was its own kind of Christmas. The bumpers didn’t eliminate the gutter balls, but the set-up helped the kids figure out what they were supposed to do. It was nice to sit back and let them have at it. They were set up for success: they got a lot more pins and they learned more quickly how to throw. By the second or third year, my nephew was ready to ditch the bumpers and bowl in a lane with the grown-ups. He bowled great games.

My kids are grown and I’ve stopped parenting, but when Sam needs support now, I try to remember to be a bumper guard, just like I did when the kids were little.

We parents need to stand on the periphery of their lives, far enough back that the kids know they are doing things on their own, but that you’re watching, too. They need that internal message that they shouldn’t worry about hitting a lot of pins, and that they are still going to throw gutters, and sometimes the ball is going to ricochet its way down the lane, but just keep throwing and try to get strong so you can throw it straighter each time. And one day you’ll be ready to go without the bumpers. You will hit some spares and strikes and you’ll throw some gutters. And it will all be ok.

I don’t always remember to be a bumper guard. A few weeks ago, I thought someone had drained Sam’s bank account. Fear turned me into a helicopter parent. Of course, my actions, ostensibly to defend his hard-earned money, upset him. And they created other problems that he needed to solve. When I remembered my role and stepped back, he cleaned up the whole mess himself.

Our culture is changing rapidly. To survive and to thrive, all of our children, not just the ones with autism, need to be resilient. We should not stand over them and help them throw all the balls. That’s not how to make a resilient kid. With each situation, each problem, each opportunity for growth, we need figure out where to install the bumper guards, stand back and let them throw.

Butterflies

Sam was spared the agony a lot of us get in the home stretch for a new job: the long wait between a successful interview and the offer. On Friday, one rolled right after the other for him. He had the best smile when he announced over dinner that WinCo hired him to work in the warehouse.

Sam sacked groceries at Albertsons for ten years. He didn’t want to become a checker. Sometimes customers are impatient. “I wouldn’t be fast enough for them,” he said. He didn’t want to stock shelves, either. I shopped late enough on the occasional Friday night to see those guys at work. Sam couldn’t be that raucous.

Nothing came his way after he graduated with an associate’s degree and certificate in computer science and technology five years ago. It was frustrating. Once I asked a manager at Albertsons if there was a way for a loyal employee with an education to move up. She shook her head no. There aren’t corporate offices here, she said.

Then Sam got a call. WinCo was opening a warehouse in Denton. They wanted to try to hire people like Sam. He would have to quit his job at Albertsons; participate in a special, six-week training class; and interview for the job at the end. There was no guarantee he’d have the job when he finished the training. In addition, he would only be paid when he was handling actual store product in the warehouse. Otherwise the rest of the training time would be unpaid. This was a Goodwill Industries program. The training included a lot of class time on “soft skills,” like getting along with co-workers, deciding when (and when not) to disclose your disability, interviewing techniques, and the like.

Sam had been in the work force for a decade. He’d been there and done that. It didn’t seem fair for him to quit a job and go without pay for four weeks. But I know I can be skeptical. It’s an occupational hazard. I kept my mouth shut. He had a chance at a job that would quadruple his take-home pay.

(Some nights he’d come home, relay what they learned that day and I’d muse over how it might be nice for the newsroom to get a “soft skills” refresher from time to time. We often seem barely house-trained–myself included.)

This week was all butterflies. I missed the open house Sunday, but Michael and Paige went with him to see for themselves what he was shooting for. We were prepared to help Sam update his resume. No need, he said, the program folks already got his resume all wrapped up. Did he want to do some mock interviewing? Nope, he said, he’d already practiced and had notecards with sample questions and answers. He’d just look them over each night, thanks.

He was visibly nervous Thursday night. A lot had lead up to that day. He made sure he had all his interview clothes ready to go and packed up work clothes, too. After the interview, he expected to be back out on the floor, in his bay, and he needed to wear a sturdy shirt, jeans and his work boots. I kept checking my phone all day for news, but that’s not his style. He was epically impulsive as a child, but now, he almost delights in waiting to deliver good news.

I don’t know who was smiling bigger on Friday night when he told me. If it were Michael or Paige, there would be lots of hugs and backslapping and arm-squeezing. But that, too, isn’t Sam’s style. I told him I’d like to shake his hand to tell him congratulations and how proud I was of him.

He kept eye contact as he extended his hand and gripped mine. Not too hard, not too soft. Up and down, not too fast and not too slow.

I kid you not, dear Internet people.

It was the first time in my life I’ve ever experienced the perfect handshake.