self-advocacy

Wear an Apron

This year marks my fourth year of pursuing New Year’s resolutions that are, at once, both big and little.

When I started out, I shared my first goal (not buying anything except food and to fix things, aka “No, Thank You”) with a few close friends and family members. Sharing your goals publicly usually increases your chance for success. For the second year, I straight up wrote a column in the newspaper. Honestly, that felt more like raising the stakes than getting a leg up, but it worked (“Yes, Please” to new experiences and long-held aspirations). This January, I quit Facebook in order to make 2019 the year of being more open and connected.

Over the past 12 months, I found myself being even more deliberate with treasured relationships, traveling a surprising amount in pursuit of that goal. Just like the years of “Yes, Please” and “No, Thank You,” a Facebook-free life can totally be “More Open and Connected” when it’s more deliberate.

This year’s goal is “Wear An Apron.” My son, Michael, and I talked it over on a recent Sunday together. He wanted to know what the big idea was behind the little idea.

I have two kitchen aprons. One I picked up at the farmer’s market in Sacramento because it says “California Grown” on it. The other my mother made for me out of fabric she picked up in Hawaii. They are both awesome and spark joy for me. But I nearly always forget to put them on until after I have already spilled something on myself.

My T-shirt drawer is full of shirts marked by my forgetfulness. I tell myself that they are just T-shirts, but the truth is, I am capable of better.

And that’s the thing about aprons. Some amazing person solved a common problem by inventing the apron. And other smart people figured out designs with pockets and loops and other features to help your apron serve you, whether you are in the wood shop or the kitchen or the printing press.

I told Michael when you think about the apron that way, it reminds you that most problems you experience have been solved by someone already. That wisdom, both small and large, is out there and ready to make life easier or better. It’s something your grandfather discovered long ago or is in a book or on YouTube or just one question away in a conversation with a friend.

Even when Sam was little and it seemed like no one knew anything, the wisdom was out there. I’ll forever be grateful to Kitty O. for showing me how to read articles in scientific journals. New wisdom. Right there.

All you need to do is put on that apron.

Whether to disclose

As part of their initial job training two years ago, Sam and his cohort at the WinCo warehouse received important information about when, or whether, to disclose their disability to others.

We didn’t give a lot of thought to this issue before sending Sam out into the world. We had always treated it as a need-to-know basis. Not surprisingly, outside of school and the workplace, most people don’t need to know.

The Texas Legislature passed a law effective this month that lets people with autism and other disabilities who drive to privately disclose their disability so the information comes up with their license plate. That way, a police officer or highway patrol officer knows there may be some communication challenges ahead and to take their time.

Other public encounters can benefit from some level of disclosure. On both of our cycling vacations, we didn’t lead our ice-breakers with any kind of disclosure. But our tour leaders and fellow cyclists soon figured out Sam’s autism. They watched what we did to accommodate him and followed suit. In Germany, it became a running joke with one woman that Sam tried more new foods than her persnickety husband did. We fielded a few questions on the side, but our travel companions were simply curious about our family; they weren’t prying.

One of the lessons Sam and his cohort learned during initial training was that disclosing your disability often isn’t necessary and that it also comes with some risk. “People can take advantage of you,” Sam told me. Sam’s rather risk-averse, so he’s not inclined to disclose and we’re happy to follow his lead.

The other night, I shared a travel horror story from one of my recent trips, in hopes that he might benefit from my experience. I thought if he ever got patted down, he should disclose his disability to the TSA agents.

In my latest travels, the screening machine flagged my underwire bra. I was upset that they intended to pat down my side. I insisted on a private screening, which really bugged them and the passengers behind me. The twenty-something girl behind me was obviously panicked about missing her flight. Magically, they flagged her every limb, and her crotch, and she let them pat her down everywhere, all the while she fussed at me for not complying. I was sad for her.

Sam said he’s never been patted down at the airport. (I’m patted down Every. Single. Time. Don’t tell me it’s random.) But he had one of his own air travel horror stories that he had not told me about before.

He was in line to board the plane when the crew announced that they were going to do a bag search at the gate. Sam was caught off-guard, as I’m sure many other travelers were. (Perhaps, dear internet readers, you know what that is about and can explain in the comments below. We could only guess what it was about.) He wasn’t able to re-pack his bag quickly and other travelers were getting impatient with him. That, of course, unnerved him even more and made it harder still for him to recombobulate. A gate attendant finally had to help him.

I told him that might have been a good time to disclose his autism–not to the impatient people around him, but to the gate attendant who was helping him. I said most people might not understand why you need more time because autism is a hidden disability. They might even be embarrassed at their ignorance and impatience for not recognizing it themselves, I said, because most people are good and want to be kind to others. I told him that as you disclose to the gate attendant, the angry people would overhear it and probably change their behavior toward you, unless they are are real jerks.

Sam disagreed that it would have been a good idea to disclose, and that is his prerogative. It’s not his job to help the world not be a jerk.

Cycling close to the sun

Sam said he liked the country roads best on our family bicycling trip to southern Italy. There are 60 million olive trees in Italy and I do believe we pedaled past a hefty percentage of them.

In this photo, you can see he stopped next to an olive tree that was a thousand years old. Some of them look great. Others are succumbing to a bacteria that came over with an insect stowed away on South American-made pallets. Many of the olive groves are small, family-owned plots that produce enough to supply the family with a little more to share. (You can buy olive oil in Italy the way we buy craft beer here in the U.S.)

On the backroads, you can trade that ten-European-cities-in-seven-days experience for a different kind of intensity. What’s not to like when you share miles of road lined by stone walls with just the occasional tractor or Italian nonno driving his 1967 Renault Quattro to the village? The roads weren’t perfect, but Sam didn’t mind dodging the potholes. Once, along a highway, I watched him drift, ever so slightly, into the main lane so that he could cycle over the rumble strips.

On the backroads, you can catch the fragrance as you pedal by chamomile, star jasmine, ginesta (broom) or the pine trees.

You can see a farmer having a sandwich in the shade of an olive tree. Another farmer stops picking to pass a handful of fresh figs over the wall to a fellow cyclist. Old men sit on benches in the center of the village and wish you “buongiorno!” The village center doesn’t look like it’s changed much at all in several hundred years.

Sam was ready for the routine, having gone on a similar tour last fall in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. We pedaled a good pace and still found time to relax in the swimming pool after covering 20-30 miles each day. Nobody lost anything along the way. The only real drama came the last day. A driver honked and then turned right in front of Paige, thinking that Paige would stop (uh, NOT) and then nearly hitting her on her bike. One of the tour leaders detoured to yell at the driver. The moment was so quintessentially Italian that I couldn’t help but live vicariously through the movie she was making for me right then and there.

Sam downloaded two dictionaries before we left the U.S. and explored the language often. He always tried to order in Italian. Periodically, he also thought of things that would increase our comfort and success in living out of a suitcase for days at a time. He inspired me to start a new checklist for our next trip — when or wherever that might be. At one point, he told me he thought he could take the next tour by himself.

He probably could, but that was never a goal of these trips. Traveling brings new perspectives. We bring some of the romance home by letting the experience change the shape of our daily lives. Sam grows through travel just like the rest of us, only a little bit more. He has always cycled a little closer to the sun.

Cake for breakfast

Early on during our bicycle trip in southern Italy, Sam announced a goal: he was going to try all the seafood he could. That was daring.

The first day, our trip leaders asked whether anyone in the group had food allergies or preferences that they needed to know. Sam’s preferences are idiosyncratic, but they aren’t hard to work around. It was easy enough to tell them that for welcome cocktails, “no alcohol, no bubbles” works for Sam. The bartenders seemed to enjoy the challenge putting together fun juice combinations for Sam. He also doesn’t like fresh tomatoes, although tomatoes cooked into sauces are ok. Even so, when something came out of the kitchen with a tomato or two – the Puglia region is famous for its cherry tomatoes – he was a sport about it.

But the seafood goal was something else altogether. The first time I can recall him being deliberately additive, not restrictive, about food. He studied entire menus in his quest. He picked classic Italian dishes: a plate of mussels as a starter, pasta with clam sauce for a first course, a swordfish steak for second. He picked unexpected ones, too, like seafood pizza. He was triumphant when he found octopus and potatoes for dinner at a seaside restaurant in Savalletri.

That’s his photo, by the way.

It’s hard not to be sentimental about how far he’s come. Sam was so food challenged growing up. As a preschooler, he would eat only breakfast cereal morning, noon and night. He hit his big growth spurt at age 15 and even though he was hungry, he limited his food choices and still refused meat. We came close to taking a second mortgage out on the house in order to pay for an intensive intervention program at Ohio State, but he turned a corner just in time. Given enough ketchup and Parmesan cheese, he started broadening his choices. Instead of eating the edge of the bun all around the hamburger, he ate the whole burger.

(Puglia restaurants are surely restocking their Parmesan supply now that we’re back home. But to be fair, he didn’t cover everything in Parmesan. We let him know which Italian foods didn’t lend themselves to that and he was happy to try without.)

Paige and I had our own dining wish lists, although we were never able to make good on eating tiramisu in Italy. The dessert at the end of the meal was usually the chef’s choice. Sweet semifreddi, gorgeous gelatins, mille-feuille — it was hard to get upset about that.

We didn’t expect that the choice of dessert sweets would be plentiful at breakfast, but there you have it. Italian masserias place many different cakes and crostada on their breakfast buffets.

We were cycling 20-30 miles a day. Heck, yeah, we had cake for breakfast.

Racing alone

Another year of equestrian Special Olympics has come and gone. Sam had an off year this year, I think in part because the regional competition had to be canceled for bad weather. He and his teammates missed some of the momentum needed in competition.

Sam remained a sportsman through the disappointments. I almost thought he wasn’t feeling it – until it was time to head back home. He was sad to leave, saying that we always have fun but the competition wasn’t what he’d hoped for. Then he added that maybe next year he would only do drill.

Sam’s been branching out as a horseman this year. For many years, he only rode English. A few years ago, he added Western events. That opened the door to barrel racing, which is a barrel of fun. This year, he added carriage driving and drill.

Sam picked out the drill music first, which brings its own kind of joy for him. He and Mal, his riding coach and drill partner, did well on their short routine, especially considering how little time they had to practice. Since no one else had a routine with such challenging moves, they were competing against themselves at state Special O. They got gold.

I understood what Sam was saying. He wanted to race alone.

There’s a moving passage in architect Nader Khalili’s memoir, Racing Alone, where he explains his internal transformation, leaving a successful practice as a high-rise architect to develop prototypes for sustainable earth architecture.

Khalili tells the story of watching his son play with his friends. They have a foot race and his son, who is smaller than the other boys, falls behind and loses. Crying, the boy tells his father that he only wants to race alone. Khalili takes his son to a quiet track and watches him, full of joy, run and run.

Our children can be such magical teachers.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #317

Sam: After we go to Italy, I might not want to ever come back.

Peggy: That would not surprise me.

First Installment

Sam’s a bona fide taxpaying citizen now. It’s a funny thing to cheer, but cheer we do — because becoming a contributing member of society is the dream of every adult, right?

When Mark died almost 12 years ago, my sister, Karen, took me practically by the hand down to the Social Security office to apply for survivor benefits for the kids. Michael and Paige were both under age 18. And eventually, Sam collected, too, because Mark was supporting him when he died.

Michael and Paige’s benefits ended the summer after they graduated high school. Sam’s benefits continued for years because he never earned enough money until he started at WinCo two years ago.

We were faithful and went back to the Social Security office to tell them that Sam got a good job and would no longer need benefits. We expected them to stop sending checks much sooner than they did.

As the checks continued to arrive, I advised Sam to save as much as he could because eventually Social Security would ask for that money back. This was not our first rodeo. Back when the agency started Sam’s benefits (it took several extra months for his to begin), no one did the math against what was already coming our way for Michael and Paige. I had no idea there were maximums or what they were for our family. And when Social Security figured it out, we owed a lot from the overpayment. It hurt, but we paid it all back.

By the time Social Security figured out earlier this year when they should have stopped sending checks to Sam, the balance due was a stunning amount of money. Sam stresses about it sometimes, but we took this as a learning opportunity.

I helped him make a repayment plan and the whole concept of budgeting is sinking in. Sam has always done a good job with his finances, but it’s not hard to do a good job when you don’t really spend much money. This time, there’s some real pressure on his earnings, and he’s figuring it out. He’s gone several months now without the safety net. And, tonight he wrote a check for his first installment to repay the overpayment.

Yep, a bona fide taxpaying citizen.

The Grand Tour

I missed the big day when the WinCo warehouse had its open house almost two years ago. Michael and Paige went with Sam, and got to see where Sam had trained as well as the spot where he works inside that massive building.

Sam will celebrate his second anniversary with the company in March. A few days ago, I took part of the day off to ride to work with him and finally get a tour of the place.

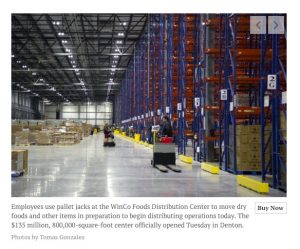

(Here’s a news story from the opening, shown in the Denton Record-Chronicle photo shown above.)

Sam’s unit unpacks small dry goods, such as shampoo and lotion, that are continuously delivered to the warehouse. They move them into bins that can be quickly accessed for shipment to stores in the region. (Sometimes he works on that repacking side, too.) They keep about 18,000 inventory bins stocked at all times. Much of the work is automated, which means he’s working with computers and all kinds of lifts and conveyors.

Once they’ve unpacked a delivery box, they throw the empty box up on a conveyor to the cardboard compactor, which was the highlight of the tour for my inner 8-year-old. The grown-up in me nearly melted watching his face light up showing me how it all worked. He is clearly enjoys his job, and is good at it — his supervisors told me as much, too.

When Sam first joined the workforce almost 15 years ago, a dear friend in the rehab department at the University of North Texas told me that Sam would learn and grow a lot on his first job. I was so grateful that he told me that, because I knew not to be surprised, and to be alert and responsive to those changes. I remember how challenged I felt entering the work force (a feeling that returns with each new job, and sometimes each new assignment, honestly), but I wouldn’t necessarily have connected to those experiences and been ready to help Sam in reinforcing his growth and understanding all of his new experiences, rather than being bewildered by them.

For example, I told him he might be surprised at how tired he would feel going from part-time to full-time work, especially such physically demanding full-time work. He was happy I shared that experience. After a few months, he was ready to advocate for himself in a powerful way: to get moved to swing shift. He knew he was not a morning person and that he needed more rest than he was able to get working day shift.

He also gained a lot more confidence in his strength. I don’t know what it is about autism, but it seems like lots of kids with autism don’t grow up with the core strength that most neuro-typical kids have. Horseback riding probably helped Sam get stronger than he was initially wired for.

But I knew WinCo put that over the top when I asked him to help me load a dryer on the back of my pickup, the kind of two-person job we had done many times over the years. I planned on taking the dryer to my girlfriend in Houston, who’d been all but wiped out by Hurricane Harvey’s flood waters. After I put down the tailgate and anchored the ramps, I turned around to see that Sam had already loaded the dryer on the dolly. He walked it all up the ramp without a word, like the grown-ass man he is.

Internet commerce is a wild web

If Sam wrote up his tips for how to avoid getting scammed, it would read something like this.

- Don’t read email

- Don’t respond to texts

- Don’t answer the phone

- Open snail mail only after your mom nags you for a week that it’s important

And still things happen to him. I try not to hover. He’s a grown-ass man. He managed to handle something this week that would make Dave Lieber and his Watchdog Nation proud: he got a refund from a seller on eBay.

Sam is working on backing up his computers cloudlessly. It means he needs some external hard drives, and some redundancy. It’s a good project for him. One of the devices he bought for the project wasn’t the right device. He sent it back to the seller. He got proof that he sent it back and the seller received it. But the seller was very slow in refunding his money. It was a lot of money–$120 or so. He complained to eBay and then he went over to his bank to see what they could do. This is where I give a big shout-out for the power of local banks who get to know their customers, because they helped turn up the heat with PayPal. Sam announced this morning that eBay is refunding his money.

Sam said, “I was starting to think that the seller wanted to sell me the wrong item and keep my money.”

That’s an excellent demonstration of being able to take the perspective of another and act accordingly, something that is hard for people with autism to do.

I told him that eBay and other e-commerce platforms need sellers to be honest or their platform becomes irrelevant. I used to not tell Sam things like that. But, he’s getting the hang of this seeing-situations-from-another-person’s-perspective thing.

He still wants a better consumer tip sheet, and he’s got a point. When he was at the bank, he learned about “verified sellers.” In the 23 years eBay’s been around, I think I’ve bought two things on that platform. I really have no idea. I’ve got my homework for the week.

And, if anyone has good consumer tips about eBay, please leave them in the comments below.

No going back

Sam lost his sunglasses in Germany.

There wasn’t anything remarkable about the sunglasses themselves. They were a pair of sunglasses that had been lying around the house for years, a little scratched, but durable both in their purpose and their terrific ability to avoid getting lost the way most sunglasses do.

Sam, myself, Michael and Paige on the Lake Constance bike trail from Bregenz, Austria, to Lindau, Germany.

The loss, though, became a valuable lesson for our family.

I knew the trip would challenge us, biking more than 150 kilometers over the course of five days. At the end of the first day’s two-hour ride, Sam turned to us and said he was confident that he had trained enough for the trip.

He had been a little nervous about it, but we set out on hourlong rides several times a week in the months before. Inspired by Michael, he also hooked his bike up to a wind trainer for regular spins.

The third day, our second full day of riding, set out as our longest ride of the week. We left our hotel in Lindau to cycle to our next hotel in Uberlingen. Most of the people in the riding group took the shortcut, taking the ferry from Friedrichshafen to Meersburg to finish the ride. We met the group and told the tour leaders that we wanted to cycle through the orchards and vineyards rather than ride the ferry.

About halfway to Meersburg, we stopped to refill our water bottles and have a snack. Sam asked where his sunglasses were. He thought someone had grabbed them for him in Friedrichshafen, where we all took a bathroom break.

No one had. Sam asked if we could go back and get them. Michael told him, “Sam, there’s no going back. We’re already pretty far from Friedrichshafen, and we’re riding 40 kilometers today.”

Sam protested briefly, but got back on his bike and plowed ahead. When we arrived at Meersburg for lunch, he was still upset. We sat at a table beside the lake and Sam tried to explain. It wasn’t going well and people were starting to stare. I invited Sam to take a walk with me to the water’s edge so he could collect his thoughts and I could make more room for listening.

There was another family walking on the little beach with their German shepherd. They threw sticks into the waves. The dog wouldn’t venture past depths over its head, but it worked hard to bring back every throw.

Eventually, Sam was able to collect his thoughts.

He understood that sometimes we help him out as a trade-off, to get things moving faster, especially when being slow is risky. But when he is responsible for himself, “I need more time,” he said. And he said that it was clear to him on this type of excursion, a person has to be responsible for themselves.

Most of us human beings don’t have enough self-awareness to assess these kinds of scenarios, let alone ask simply and directly for the fix. Sam constantly amazes me with this gift of his.

We went back to the table and announced the findings. We all agreed we could and should slow down our transitions. Paige asked Sam about a checklist. What if each of us went through a checklist, like an airline pilot, before we cycled on? The process helped us slow down for Sam and, at one point, also kept me from losing my cycling gloves. We often were the last ones of the cycling group to leave, but because we rode fast, it all worked out in the end.

I told Paige later that day that I did have a secret hope that the trip would stretch the family, although I wasn’t quite sure how. I hoped we wouldn’t be miserable, but I didn’t worry about it either.

Learned helplessness does someone like Sam no service at all, and some of that was coming from our habits to take shortcuts and speed things up. He deserved more from us. We learned we could step back, let some conflict points rise up and not freak out. After all, Sam is a grown-ass man.