adults with autism

See Sam Drive, Horse and Cart Edition

Sam started driving lessons about two years ago. Sam would watch other riders at Born 2 Be dress up in costumes and drive their carts in exhibition drills that he enjoyed watching. I mentioned he didn’t have to resign himself to watching, he could participate and he finally decided to give it a try.

Today wasn’t his first competition, but it was the first time I was able to go and get video for you, dear internet readers. We got to the stables (near Terrell) about 9 this morning, in time for Sam to watch his instructor and many of the other competitors. His class was the last of the day to compete, and he was the last competitor. (You will see that he is joined in the cart by his instructor as a safety measure. Also, we very grateful that it was all done by noon. We both napped after we got home. It’s going to be a long and very hot summer this year.)

He said that he planned to trot the “Fault and Out” course. He’d seen a few people scratch over the course of the morning, but he was confident in his ability, along with Doc’s, to weave the cones. You can hear the whistle after the sixth set. In the stands, we were all surprised to hear the whistle because it looked like they were through, but Sam knew. He had to stop because he and Doc had knocked a tennis ball off the top of the cone. That’s the Fault. So they were Out.

Things went better for the Gambler’s Choice obstacle course. I learned that this, too, is a timed event, unlike trail patterns for riders. The more times he and Doc completed one of the obstacles, the more points they got. You will see that Sam started to try to back Doc and the cart into the U and bump out the back, but when things slowed down too much, he wisely gave up. I learned later that it’s quite difficult for a horse to back a four-wheel cart without jackknifing it.

After the events were over, one of the technical judges came by to encourage Sam and tell him what all went right. Sam told her he just wanted to finish the course anyways, because it was fun.

Racing alone. That’s the spirit.

Look for the Paul Hollywood handshake

For the first time in three years (thanks, pandemic), equestrians gathered for the statewide Special Olympics in Bryan last weekend. Sometimes, it felt like we hadn’t missed a beat (showmanship classes rolled like clockwork Sunday morning even though we were tired from the dance the night before) and other times, the grief over the lost time hit hard (hello, friend I haven’t hugged in five years).

I have to tip my hat at the organizers that recognized the athletes would benefit from an icebreaker after all these years. They outfitted each athlete with four of the same pins for their region. They had to meet riders from all the other regions in order to exchange pins and collect a full set: North, South, East, West.

It was fun to watch Sam and all the other athletes not only reach out to one another, but help one another complete their sets. God bless those who came all the way from out west to Bryan, which is in south central Texas.

Sam competed in five events in all. Many athletes in his classes are like Sam and have been riding for years. They are skilled and consistent riders. Some have their own horses. Some compete in able-bodied shows. Every once in while, though, it’s just Zen and the Art of Horsemanship and as it unfolds in front of you, it’s pure joy. I’ve posted video from all five of his events, but it was Working Trail where I wondered whether the roof would open and sun rays would shine down on Sam and Madrid, like in the movies. It was magical.

There are two moments you’ll want to savor. First, when Sam and Madrid are at the gate and you can see he knows how tell Madrid to sidle in closer so that he can easily remove and re-attach the rope. Then, the judge stands up, says “wow” and comes over to shake Sam’s hand.

A photo from the awards ceremony, courtesy of Yolanda Taylor, parent of one of the other athletes in this event:

Never been to Spain, finally made it to Maine

Sam and I were supposed to go to Spain last year. We booked a cycling tour with the same outfitter that took us to Italy and Germany, and Paige and me to Ireland, over the past several years. We booked before the pandemic, but even as the lockdown began, we were thinking, naively, that with a little luck, the virus would be under control by summer, when the cycling tour would take us through the countryside around Cordoba, and into Seville and the Alhambra. Ha. Spain was being ravaged by the virus by then, and our country was on the verge of its own, first big wave. About six weeks out, the outfitter canceled the trip and refunded our money.

Sam and I biked around town last summer. It was very quiet.

When the tour catalog came for summer 2021, it seemed unrealistic to make any kind of plan to go abroad. Even the handful of U.S. tours they had, though they looked to be as much fun, felt risky. But we had to have a little faith. Our world had gotten really small. I wondered if we didn’t try to make something special happen, our mental health would suffer even more than it was. The vaccine roll-out had begun. Maybe a fall tour to see the leaves in New England could be a safe bet. Surely, the virus would be subsiding by then. Ha ha.

The company’s tours to cycle in Vermont filled up fast, so we missed that. They offered a self-guided tour of Acadia that we’d heard was good. We booked for the first week of October.

Ever since the vaccine rollout, Sam has been pushing back on letting our lives get too busy again. He wants more “thinking time” for math and signal projects he’s working on. He likes the quiet pace we found, and I agree it’s a treasure to keep. While traveling to Maine was a little discombobulating (we were really rusty with the whole packing-parking-screening thing), once we got there, it was exhilarating–as you can see below, with the boys checking the view from the Bar Harbor shoreline our first night in town:

We cycled all through Acadia National Park, learned about lobstering (and ate a lot of it), watched the stars, and got out on boat rides several times. During one nature cruise, our guide, a retired park ranger, asked how many of us would have gone abroad this year but came to Maine instead. About half of the 50 people on that boat raised their hands. Even the guide was a little surprised. Later, we visited about that moment with one of the wait staff at a brew pub who also worked part-time at the local visitors bureau. She said that they, too, had noticed many more people requesting information this year. Good for Maine.

Sam’s favorite part of the trip was that nature cruise, which took us by some of the favorite hangouts for seals, porpoises, and sea birds, including two huge osprey nests. We also saw some stunning homes along the shore. My favorite part of the trip was cycling the carriage roads through the park. They were so quiet.

The Silver Linings Playbook

The world will break your heart ten ways to Sunday. That’s guaranteed. I can’t begin to explain that. Or the craziness inside myself and everyone else. But guess what? Sunday’s my favorite day again. I think of what everyone did for me, and I feel like a very lucky guy. — The Silver Linings Playbook

Sam and I were invited to the wedding of some old friends last weekend. The couple had postponed their celebration because of the pandemic, but like most of us looking for a little bit of normal, they, too, saw the covid vaccine as a way through to their special day. We said yes to some beautiful normal that day, although we still weren’t quite feeling fully normal. We masked up for the ceremony and stayed out on the patio for the fun. It was the best day.

Sam hasn’t been able to go dancing–one of his favorite things–much at all for the past year and half. He joined an Eastern swing dance club several years ago, but they closed with the first covid lockdown last year and opened for a club dance only once, as far as Sam can tell, just before the surge of the delta variant put a damper on everything again. I think the only time he’s been out is when his aunties took him dancing on a mountain biking trip in June. (Remember June, when we thought we were finally free of it?)

On the way to the wedding, I told him there would be a DJ and music and a chance to dance. He said he wasn’t sure about staying at the party that long, let alone dancing. “It’s risky, Mom,” he said.

But, as you can see in the photo above, his eyes were soon on the dance floor. He waited for a bit, hoping a the DJ would spin a good swing dance number, but after a few tunes, he decided he would just make his move. He danced quite a bit, including at least one number with the bride. He’s a lucky guy that way.

Overheard in the Wolfe House #326

Sam (after sitting down briefly in the easy chair, rises and returns to kitchen): That pizza’s gotta cook. I’m hungry.

Conservative guardianship

Britney Spears’s battle to be free of the conservatorship that has governed her affairs touches familiar themes for us old-timers in the disability world. She’s asking for the grown-up version of the least-restrictive environment, the federal right of children with disabilities to receive a free, public education alongside their peers in regular education classes, with support, if necessary.

For now, the least-restrictive environment is the best way we know to ensure every child has access to all they need to learn and grow into their best selves.

Over the years, I’ve seen a few families struggle to understand what guardianship really means. Adults need a least-restrictive environment, too. When Sam approached high school graduation, we were told that, as his parents, that we’d better think about setting up guardianship before he turned 18. It has been a few years now, and perhaps understanding has improved among the teams that do this transition planning, but at the time, Mark and I really thought that recommendation came out of left field. We’d fought for Sam his whole life for him to be included at school and in the community, to be in that least restrictive environment. Something about guardianship felt very restrictive to us.

Then an older, wiser friend boiled it down for us. “You’ll have to tell a judge, in front of Sam, that he’s incompetent.” I can still see Mark’s face when he realized what that meant. “We could never do that to Sam,” he’d said. To which I’d replied, “oh, hell no, we couldn’t.”

I often bring the salt, just FYI.

For our family, that ended the guardianship discussion right there. I did poke around a little, however, to figure out ways we could be his bumper guard. Once you start looking around, there are all kinds of ways to be there for someone, even in a somewhat official capacity, from bank signatories to putting both names on a vehicle title to advance directives and more–all without ever stepping foot in a probate court.

Last week, I learned even more about the power of supported decision making, an alternative to guardianship that gets you in the door when your loved one really needs you. These documents are legally recognized, even if your loved one is ensnared in the criminal justice system. One-page profiles can also help a lot for those times you can’t get in the door–when your loved one is in the hospital with covid, for example.

When your loved one truly needs a guardian, it pays to be thoughtful and as minimally restrictive as possible. That can be tough in Texas, just another FYI.

This year, advocates helped defeat a troubling bill filed in the Texas House of Representatives during the last regular session. If it had passed, the bill made it too easy for parents to get and retain guardianship of their teen. The legislation was inspired by one family’s tragedy, but it was rife with unintended consequences that would have stripped many young adults of their autonomy—especially if special education transition teams in Texas school districts are still advising parents to pursue guardianship without thinking it through.

Refrigerator Mother 2.0

Only a few generations ago, some doctors blamed mothers for their children’s autism. Psychologists wrote long theoretical papers based on their observations of mothers and their children. They concluded that autism mothers were cold and that their lack of love triggered the child’s autism.

If you stop to think about that idea for a minute, those explanations were quite a leap. And a cruel one at that.

We humans look for patterns in the world around us–it’s almost one of our super-powers. We use the information to make meaning, and create loops of ferocious thinking that make the world around us a little better.

Therefore, knowing that we’re supposed to make things better, the Refrigerator Mother explanation for autism just begs the question. How much did those early theoreticians consider and—most importantly, rule out—before concluding they’d observed a pattern of mothers who don’t love their children?

Granted, many people were immediately skeptical of these mother-blaming theories, including other professionals and autism families. The theories fell after a generation, but the damage was done to the families forced to live under that cloud as they raised their children.

And, the blame game is still out there.

The latest iteration has started in a similar way, with people seeing problematic patterns in autism treatment. Young adults with autism are finding their way in the world. Some of them had good support growing up, but the world isn’t ready for them. Some of them had inadequate support growing up, so they have an added burden as they make their way in a world that isn’t ready for them either. Some are speaking up not just about the world’s unreadiness but also about that burden. We must listen. Autistic voices can help us find new patterns and new meaning and build a better world for all of us.

We should be careful about letting one person’s experience and voice serve as the representation for the whole, because that’s how the blame game begins. Even back in the old days, when information was scarce, we had the memoirs of Temple Grandin, Sean Barron, and Donna Williams to show us how different the experiences can be. As Dr. Stephen Shore once said, if you’ve met one person with autism, then you’ve met one person with autism.

Here’s an example of how that can break down: some now argue that asking an autistic child to make eye contact, as a part of treatment service, is inherently abusive because eye contact feels bad for them. Missing from that argument is the basic context, the understanding that for humans to survive, we need to connect to one another. For most of us, eye contact is the fundamental way we begin to connect, from the very first time we hold and look at our new baby and our baby looks back at us.

I asked Sam recently (and for the first time) whether making eye contact is hard or painful for him. I told him I was especially curious now that eye contact changed for all of us after living behind face masks for a year. He said this, “Eye contact is very powerful. I wonder whether I make other people uncomfortable with eye contact.”

He’s right. It is powerful. And he just illustrated the point about one person’s perspective.

When Sam was young, we never forced him to look at us. But after a speech therapist suggested using sign language to boost his early communication, I found the sign for “pay attention” often helped us connect.

The additional movement of hands to face usually sparked him to turn his head or approach me or Mark in some way, so we were fairly sure we had his attention and that was enough to proceed with whatever was next. Over the years, we’ve shared eye contact in lots of conversations and tasks. But if not, we recognized the other ways that we were connecting and I didn’t worry about it.

All of this context—both the need to survive and the difficulty with a basic skill needed for that survival—cannot go missing from any conversation about the value of teaching an autistic child. Some people with autism do learn how to make eye contact early on and are fine with it. Some don’t. For this example, then, we can listen carefully to adults with autism and their advocates as they flag patterns from their bad experiences with learning to make eye contact and make changes. But that fundamental need to connect and share attention remains.

That’s when we also need to remember our tendency to blame others when our troubles feel intractable. Sometimes, in these fresh arguments over how autism treatment should proceed, I hear that same, tired pattern of blame I’ve heard since Sam was born. Take it from a worn-out mother who’s been blamed plenty over the years: some arguments are just another round of the same, they just come inside an elaborate wrapper of mother’s-helper blaming instead.

All the families I know truly love their children and are learning how best to respond to them. We can’t forget that parents have a responsibility to raise their child as best they can. Let’s talk, please. But please also, let’s spare the rollout of Refrigerator Mother 2.0, because it could cost us a generation of progress.

Power outages and the power of plain language

Save the warnings by the National Weather Service, our household would not have been prepared for the freezing weather and massive power and water losses Texas suffered last week. From late Sunday night through Thursday afternoon, we endured rolling blackouts as two separate winter storms came through North Texas. Unlike many Texans, we didn’t lose our household plumbing in the cold, but our city’s system lost water pressure and we were without safe drinking water from Wednesday afternoon through Saturday morning. We also had no home internet service for most of the week.

As the meteorologists gave their forecasts, the conditions looked to me much worse than they did in 2011, the last time we had a day of rolling blackouts. Since that debacle, I’d read Ted Koppel’s book “Lights Out,” a sobering assessment of life after a catastrophic grid failure. Sam has friends who eventually gave up on living in Puerto Rico post-Maria. I recognized the incredible risk embedded in that forecast. We prepared like a hurricane was coming, with extra food, water (including filling the bathtub), and other provisions. We sheltered our plumbing as best we could.

If we had been waiting for cues from state or local public officials, we would not have prepared.

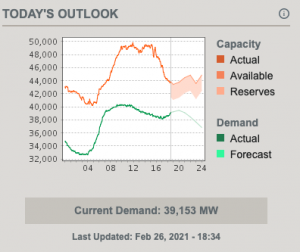

Once the crisis began, it was hard to explain to Sam what was happening. We had little official information to go on. For example, I couldn’t tell him when we might be able to depend on having power again, because no one was saying. I showed him the homepage for the state’s power grid, which has a good visual for what’s happening at the moment. On the outage days, there were bizarre spikes in future capacity, as if ERCOT expected four or five generation facilities to come back online at any moment.

Of course that wasn’t what happened. During the second day of rolling blackouts, we would get a phone call once or twice a day from the city utility, telling us to expect rolling blackouts for the day or night. But those calls said nothing about the grid status or when power would return.

After meteorologists called for warming on Saturday, we made contingency plans to get through to that day. I warned Sam that the power might be unreliable for days or weeks afterward. Power companies had rotated the power off in some places and couldn’t rotate it back on. That could mean the grid is damaged in places, I told him.

Also, when the blackouts started, I couldn’t tell him when the power would be on or off. There was no discernible pattern and we weren’t told. After about 24 hours, the city’s robocalls suggested a basic pattern, although we predicted it more closely using our oven clock as a reverse timer. We also observed street lighting changes as a predictor when we’d be shut off. If it was particularly quiet, Sam could hear the power coming back before the lights went back on. As a result, we could plan for things we needed to do to survive, like prepare food or charge our phones.

But that adaptive mode was ours to determine, and sometimes I had to coach Sam through it. Nothing was ever suggested to us by a public official how to cope with rolling outages, or how cold your home could get before it became too dangerous to sleep there, and the like.

When the city’s water system failed, our city made daily phone calls with recorded messages. They told us when the system was failing and how to help, then they told us when it failed, then they told us how recovery was going, and finally they told us when it was safe to drink again. That communication helped.

Sam does well with most of what adult life throws at him, but one of the few things he still struggles with is “official” communication.

Frankly, we all do better when public officials communicate with us in plain language. That is one reason why the federal government adopted the Plain Writing Act of 2010. I recognize the writing style when I get a letter from the IRS or the Social Security office. They always write in plain language so that even when your situation or the law around it is complicated, they use vocabulary and syntax you can understand so you can act accordingly.

For people with autism, such plain language communication is vital. Sam would likely have suffered greatly in last week’s outage without someone with him to translate what little information we were getting and work to fill in all the voids. ERCOT wrote arcane tweets about load-shedding, for example, and asked people not to run their washing machines. Still shaking my head about that.

We’re both still recovering from the trauma of last week. The trauma was made far, far worse by the lack of communication from state officials. As they set up their circular firing squads in Austin this week, we are learning that they knew this problem was coming and they knew it was a problem of their making. I’m sure individuals were panicking and that made it difficult to make good choices, but that’s why, in calmer moments, they are supposed to write and practice emergency plans. This was foreseeable and preventable. However, in my darkest moments, I sense that the lack of communication was a choice, one they made in part to avoid blame.

This week, I’ve also been stunned by how many people stung by this abject failure expect it to happen again. They simply do not expect our state to be able to fix this mess.

I want to reject that premise, but, mercy me, if it happens again, can they at least have the decency to communicate to us, and in Plain Language?

Lessons of calculus

Sam didn’t learn calculus in high school and has decided, now that he’s in his 30s, that this deficit in his education must be remedied – not just for him, but for me, too.

I was a bit of a math whiz in junior high and high school, and while I didn’t get much calculus instruction either, I was somehow destined to review algebra, geometry, and trig lessons at least once a decade as the kids grew up and as Sam struggled with advanced algebra classes in junior college. To share in Sam’s enthusiasm for this new endeavor, I picked up Steven Strogatz’s book, Infinite Powers. It’s a persuasive little tome about the secrets of the universe and the author has nearly convinced me that God speaks in calculus. (And, perhaps that is why we have a hard time understanding Him.)

Sam doesn’t need all that. He just wants to master the principles and formulas (Hello, Kahn Academy) to break free of the limits he feels in his amateur music and sound studio, acquiring the demigod ability to manipulate the sound waves his computer produces.

Sam and I have been chipping away at this calculus thing for several weeks, beginning with a thorough review of the fundamentals. We know you can’t do the fancy moves until you’ve got the basic blocking and tackling down cold.

Through this journey, I’ve watched Sam learn a lot when we make mistakes. Kahn Academy tutorials ring a little bell and throw confetti every time you get an answer right. We don’t stop and think about how we nailed it. However, get the answer wrong and we are motivated to go back to find the missteps. Somehow, examining that failure locks in the learning just a little deeper.

Some writers and thinkers dismiss the fandom that failure gets in the business community. (Failing Forward! How to Fail like a Boss!) They are right: platitudes can’t turn failing into big money and success. That whole ready-shoot-aim philosophy just gets you muscle memory for ready-shoot-aim, in my experience. Examining your choices and, importantly, your knowledge deficits before making changes is what gets you back on the path of progress.

When I was in graduate school at the Eastman School of Music, some of us sat for a short, informative lecture from brain researchers at the Strong Memorial Hospital (both the school and the hospital are part of the University of Rochester). They showed us how the brain looks for motor patterns in the things that we do (walking, for example) and then files those patterns with the brain stem once established. It makes our learning and doing more efficient. But, of course, for practicing musicians, that tendency is a terrifying prospect. Practice a music passage wrong often enough and your non-judgmental brain says, “Aha! Pattern!” and files it away for safekeeping. The last thing you want is for that incorrect pattern to trot itself out when you are stressing. That’s how mistakes happen in a big performance. And they do. All. The. Time.

Sam and I are doing our best to go slowly and learn how to work the principles and formulas right the first time, or at least going back to retrace our steps when we trip up so we walk it through correctly on the second pass.

We’re learning calculus, the secret of the universe.

The man, the mail-in ballot, and meaning

Sam signed up for mail-in ballots after the pandemic began. Texas allows individuals with disabilities and voters age 65 and older to vote by mail.

He registered as a Republican after learning that he would miss at least one upcoming local election if he didn’t. Turns out, he got two test runs with the mail-in-ballot routine before the big one — the November presidential — arrived. In mid-July, Denton County had a run-off between two GOP nominees for state judge in the 431st District Court. Then we unexpectedly had a crowded race of Republicans and a lone Democrat vying to succeed our former State Senator, who let no grass get under his ultra-ambitious feet as he hopscotched his way from newbie Texas resident and the state legislature into Congress this year.

When the November ballot arrived in the mail in early October, Sam opened up the envelope and spread its contents across the dining room table. He grabbed a pen and colored in the box to vote for president. He took a deep breath, saying that it felt powerful to vote for Joe Biden. He stood up and announced then that he would come back to finish the rest of the ballot later.

The ballot was long. It included federal, state, and county offices. It also included city offices, as the Texas governor postponed local races because of the pandemic. When Sam returned to finish voting, he surprised me how prepared he was to make informed choices all the way down.

He’d been watching our current president, and deteriorating conditions for a long time. He had thought long and hard about how to vote for change.

Our current president proved himself irredeemable to us when he mocked a reporter with a disability in 2015. The past four years have been so bad that it was genuinely shocking — and should not have been — to watch Joe Biden return the affection of a man with Down syndrome who rushed to hug him several years ago.

It’s a hard thing to explain to people who haven’t been on this journey, what it is like to regularly experience another human being’s black-heartedness in a deeply personal way. When Sam was little, we shielded him. Now that he’s an adult, we have to talk about it.

Those are the worst conversations. Not because Sam gets hurt, or because we don’t have strategies for him, but because we parents are hard-wired to protect our children. When I hear these stories, or watch things unfold in front of me, I want to slap somebody. I haven’t so far, so I guess the strategies are working for me, too.

Sam told me about a week before Election Day that he was going to want to watch the returns on election night, in hopes that his choice would prevail with everyone else. Election night was tough, but as the days went by, you could see the tension lift. Sam is not just relieved, but happy.

“I voted for Joe Biden as hard as I could,” he said.